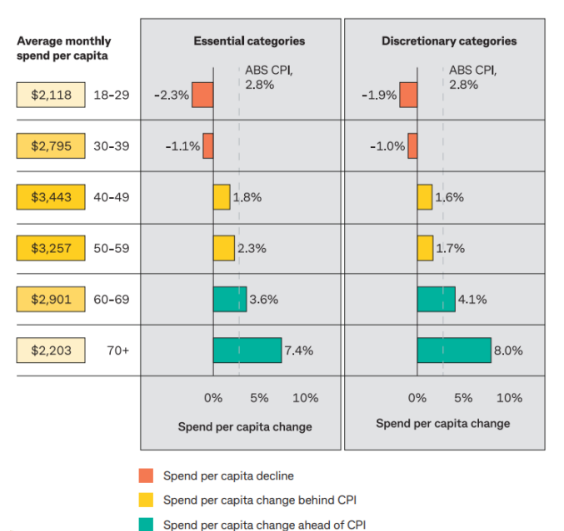

Nothing better sums up the divergence of economic fortunes between young and older Australians than this week’s analysis of spending habits by age from the CBA.

Source: CBA

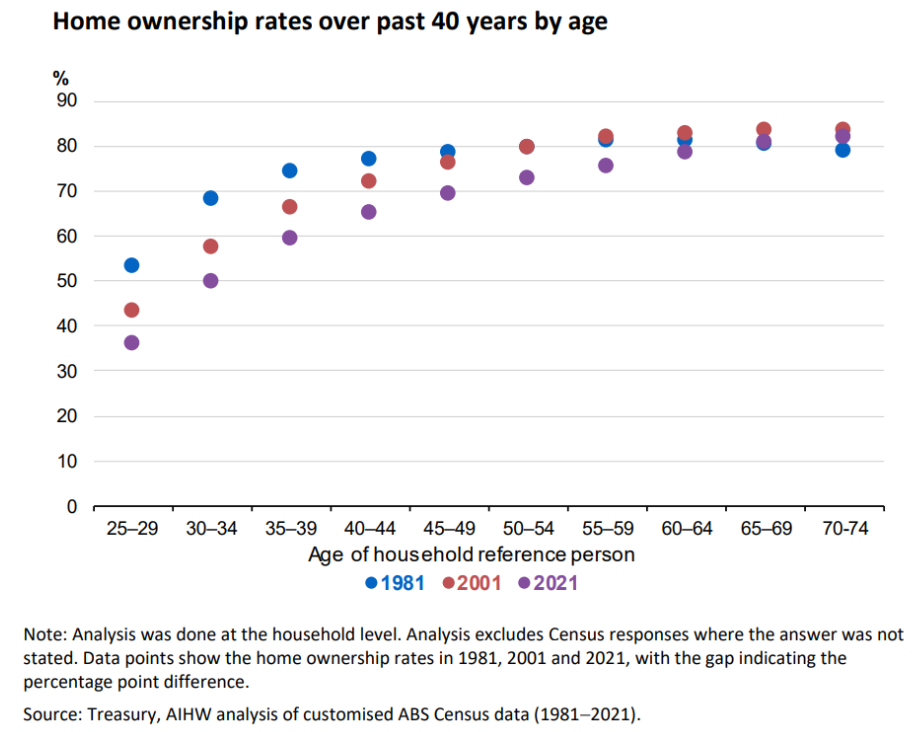

The only chart that comes close is the following, showing the collapse in home ownership rates among younger age cohorts, while older age home ownership rates have remained stable.

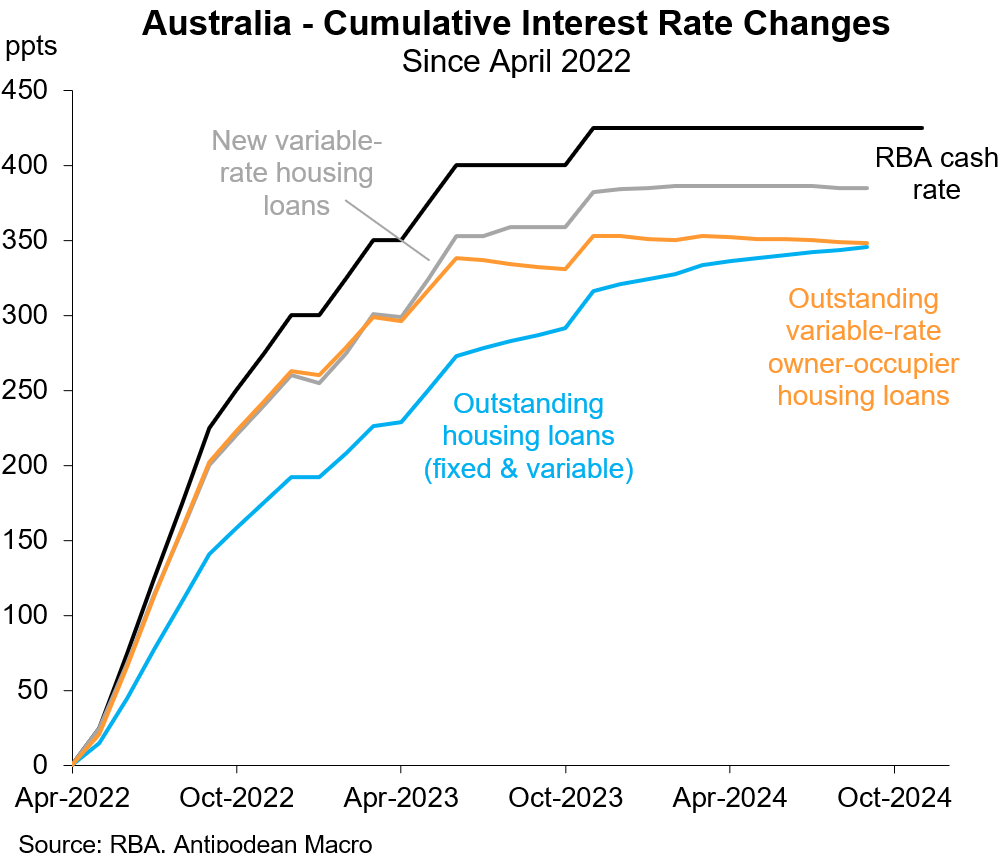

As shocking as the first chart on spending is, it is precisely what the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) monetary tightening was designed to achieve.

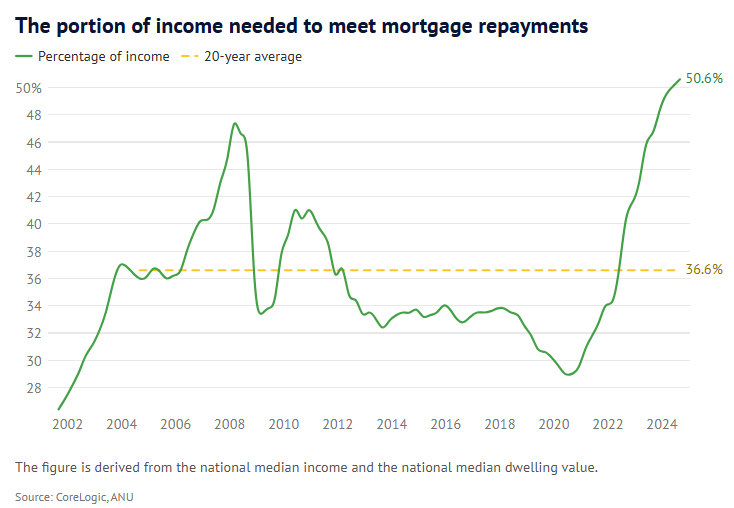

The RBA’s aggressive interest rate hikes were explicitly designed to hit Australians with mortgages, who tend to be younger households.

Households with mortgages have experienced a circa 50% increase in mortgage repayments, which has significantly curtailed their disposable income.

At the other end of the spectrum, older households have enjoyed an increase in interest rates on deposits, which has boosted their disposable incomes.

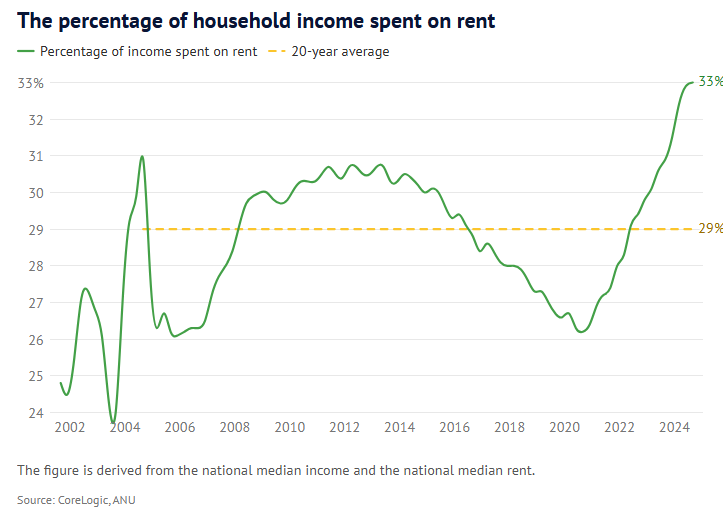

The other factor that has significantly eroded younger Australians’ disposable incomes and, thereby, spending is the dramatic rise in rents.

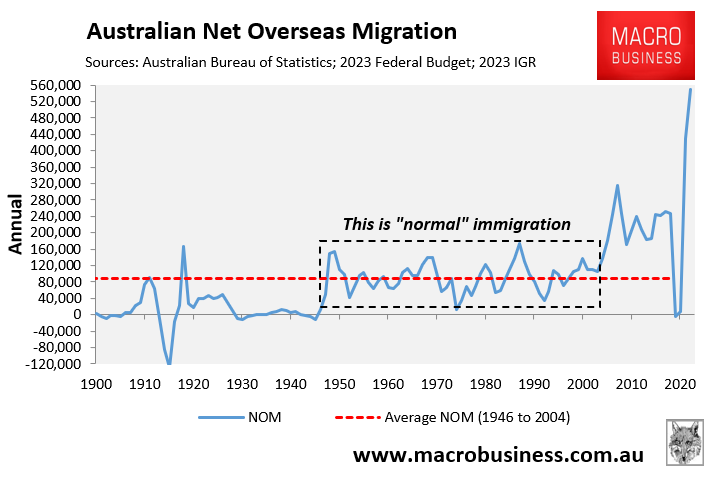

However, the surge in rents has been driven by excessive levels of immigration, rather than monetary tightening by the RBA.

Nevertheless, older Australians have been largely shielded from the rise in rents because of their much higher home ownership rate of around 80%.

Ultimately, the RBA’s monetary tightening is doing what it was designed to do: slowing aggregate demand by hitting those with high levels of mortgage debt, who tend to be younger.

It is an intergenerationally unfair system. However, it is the only RBA tool to manage inflation.

The bigger question is: why hasn’t the federal government stepped in to help the RBA and distribute the pain more evenly among the generations?

Unfortunately, the federal government has worsened the situation for younger Australians by running the largest immigration program in history, thereby driving up house prices and rents.