The similarities between the Canadian and Australian governments concerning immigration and housing are astounding.

In 2022, Canada’s then-immigration minister, Sean Fraser, saw immigration as a race for global talent, which he always intended to win.

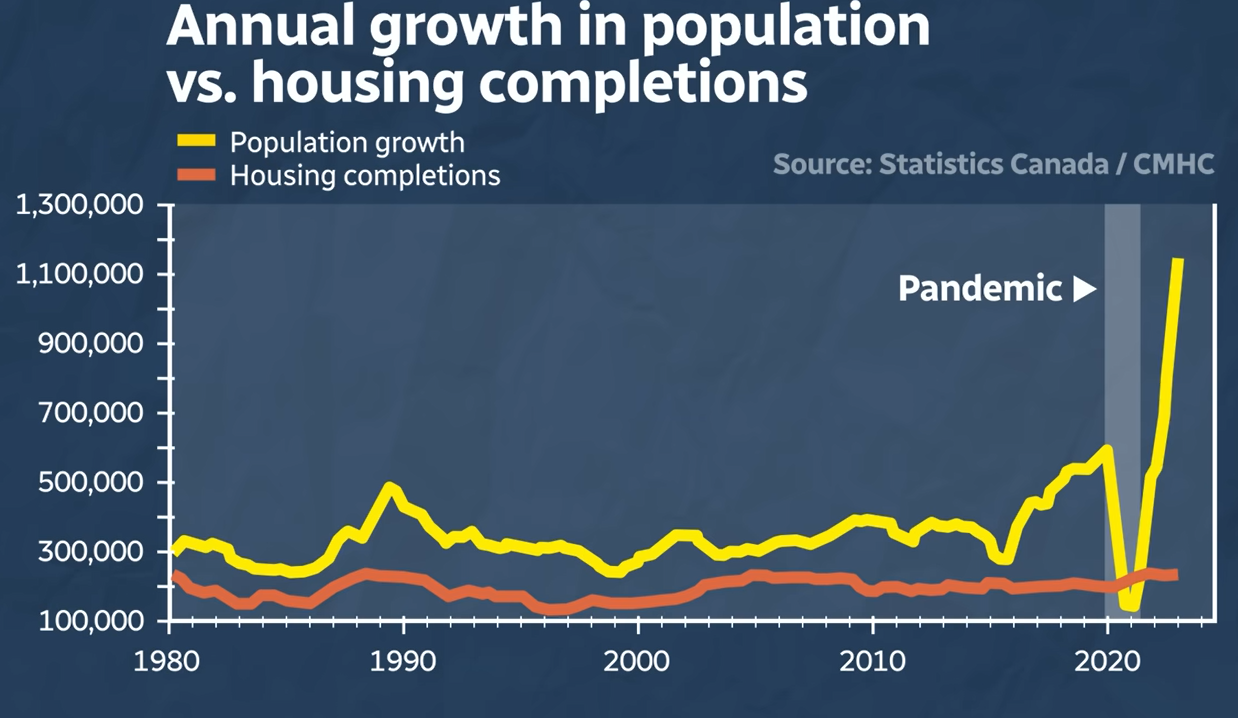

In 2022, Canada experienced record population growth of around 800,000. Still, Fraser announced that Canada would welcome 465,000 permanent residents in 2023, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025.

“If we don’t do something to correct this demographic trend, the conversation we are going to have 10 or 15 years from now won’t be about labour shortages; it’s going to be about whether we have the economic capacity to continue to fund schools and hospitals and public services that I think we too often take for granted”, Fraser said in 2022.

Canada then experienced a record immigration boom that increased Canada’s population by more than 1.2 million people last year, creating an unprecedented housing shortage.

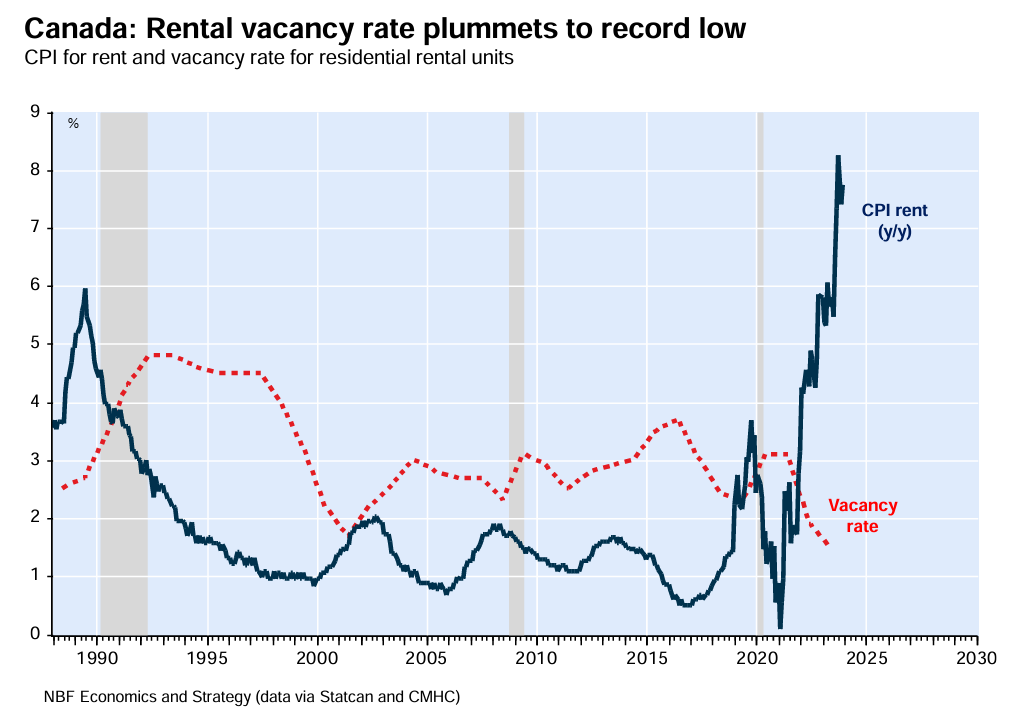

This unprecedented imbalance between population demand and supply caused rental vacancy rates to collapse to all-time lows and rental inflation to surge to a record high.

Yet, despite engineering Canada’s housing crisis via reckless immigration levels, slick-talking Sean Fraser was made housing minister in July 2023.

“I know we are going to solve the housing crisis because I know what Canadians are capable of”, Fraser said upon his appointment.

There is a clear mismatch between how fast Canada’s population is growing and how long they need to supply housing, services, and infrastructure like health care, schools, roads, public transit, etc.

The shortages affect all layers of society but are most acutely visible in the cost and availability of housing.

Australia has followed a nearly identical path.

In 2022 and 2023, then Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil promised to accelerate immigration citing skills shortages and a “race for global talent”.

O’Neil stated that immigration had been the “special sauce in our national story” and called for more.

She said that Australia needed to shift “away from a system which is almost entirely focused on how we keep people out to one that recognises that we are in a global war for talent”.

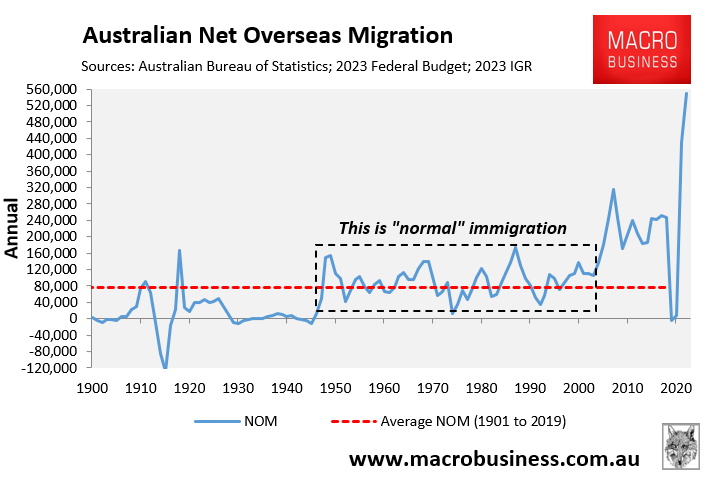

Australia then experienced the biggest boom in net overseas migration in the nation’s history.

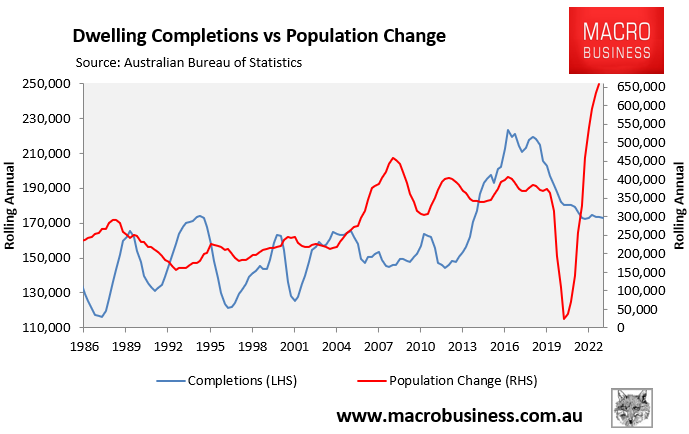

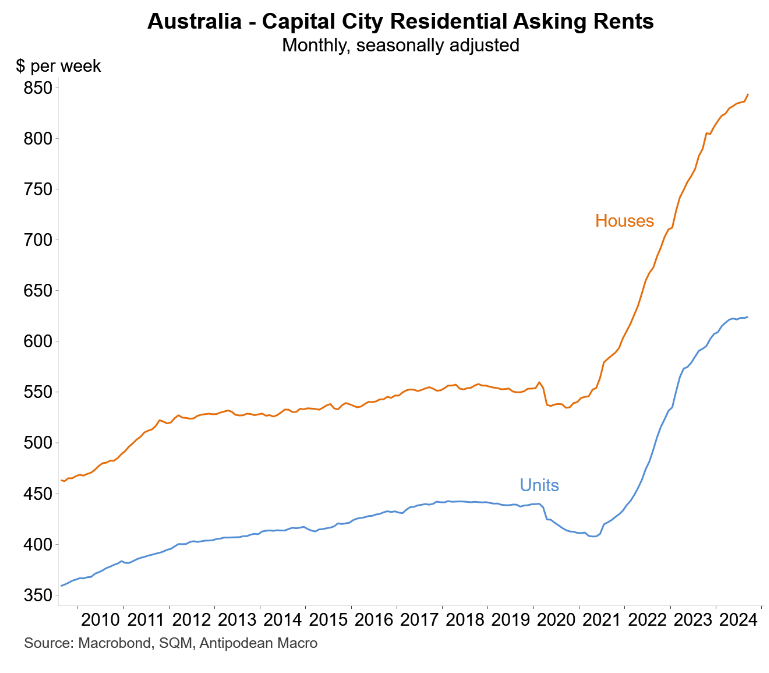

A massive mismatch developed between population demand and housing supply.

Rental vacancy rates collapsed to historical lows and asking rents skyrocketed.

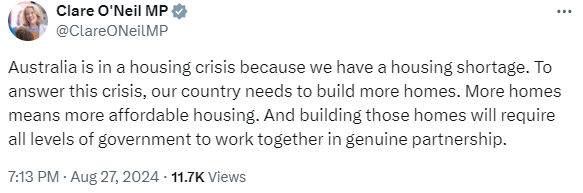

After creating the rental crisis via reckless levels of immigration, slick-talking Clare O’Neil was then shifted to housing minister in August 2024.

O’Neil even had the nerve to claim that “Australia is in a housing crisis because we have a housing shortage. To answer this crisis, our country needs to build more homes”:

O’Neil conveniently failed to mention that Australia has a shortage of homes because she, as Home Affairs Minister, imported one million net overseas migrants in only two years, which overwhelmed supply.

It is almost as if Australia’s Albanese government has taken its cues from Canada’s Trudeau government.

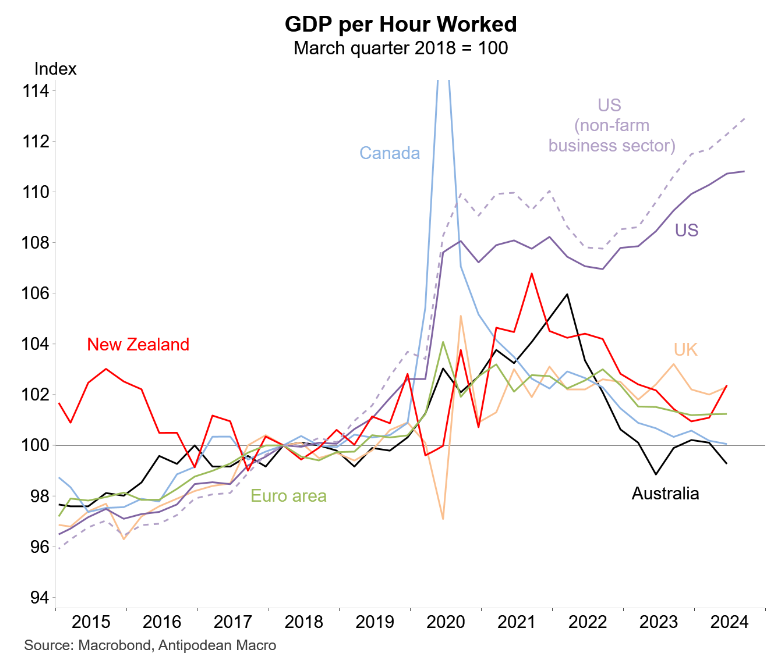

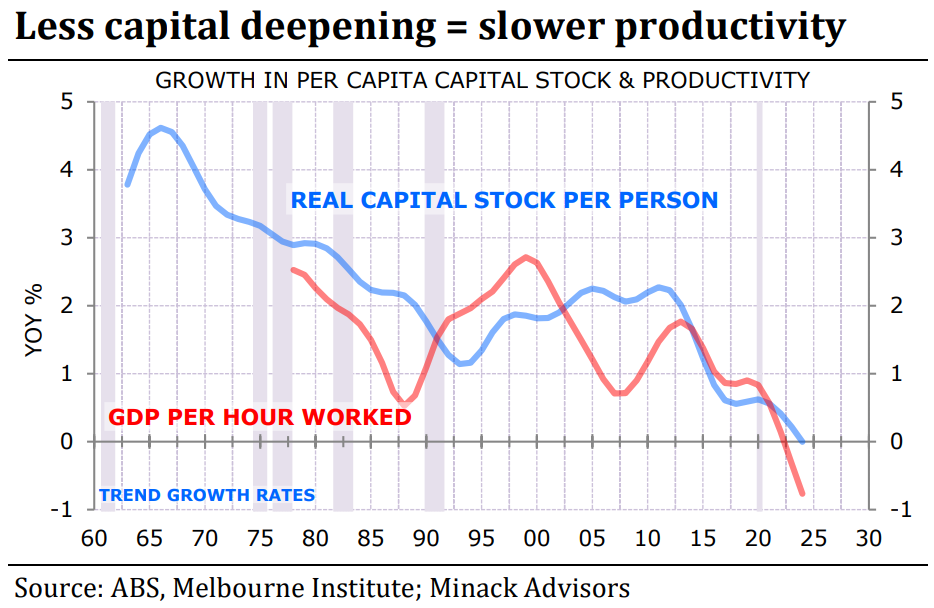

Both nations have been left with housing crises that will take years to repair (if ever) and stagnant productivity economies with collapsing living standards.

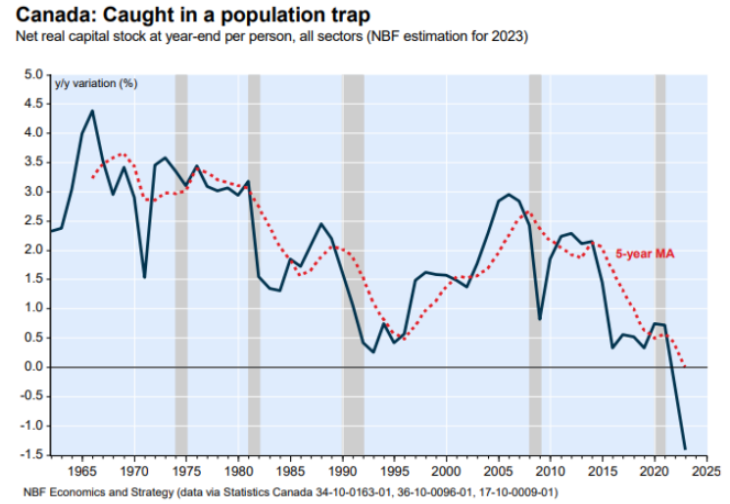

Both nations suffer from acute “capital shallowing” because population growth via high immigration levels has run well ahead of business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

Australian capital shallowing

Canadian capital shallowing

Both countries are textbook examples of what not to do if the goal is to raise the living standards of the incumbent population.