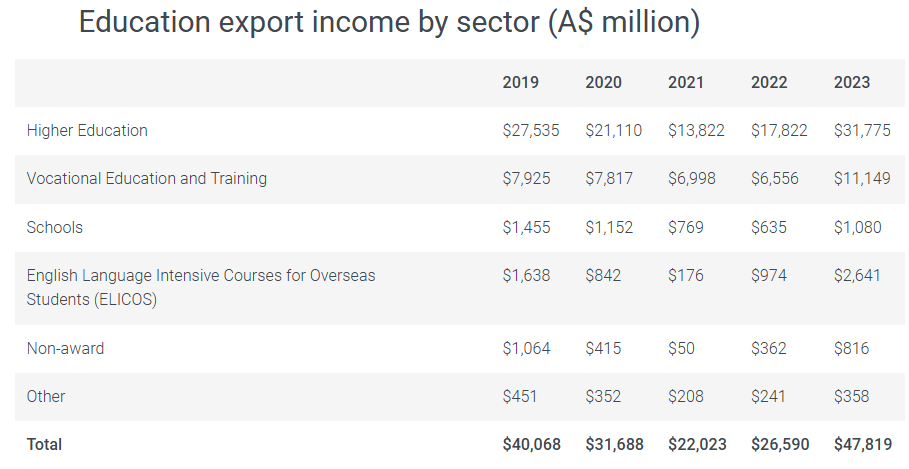

I have argued repeatedly that the purported $48 billion education export figure published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is exaggerated and massively overstates the benefits of international students to the Australian economy.

Source: Department of Education

The ABS obtains this impressive export statistic using “an average spend estimate from Tourism Research Australia … supplemented by the addition of the total expenditure on course fees”.

The ABS improperly labels all spending by international students as exports, even when the expenditures are paid for with earnings from Australia.

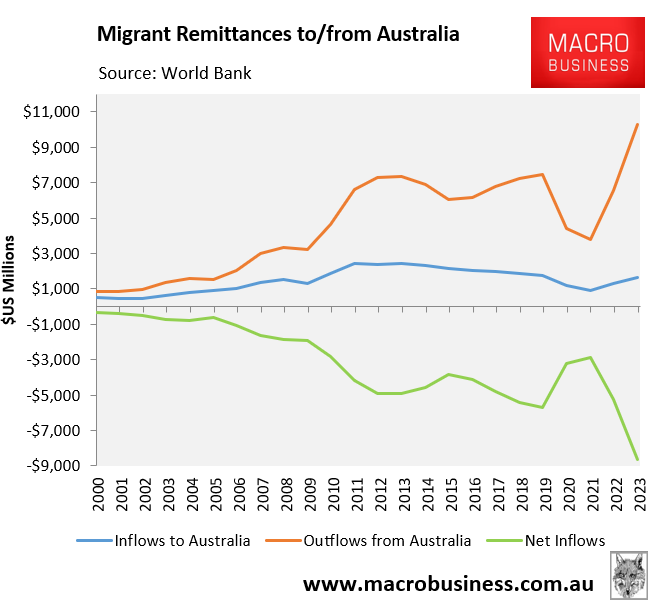

The following chart displays World Bank data on migrant remittances to and from Australia:

In 2023, migrant remittance inflows to Australia were only worth $US1.6 billion, while outflows were at $US10.3 billion, resulting in a record net outflow of $US8.6 billion.

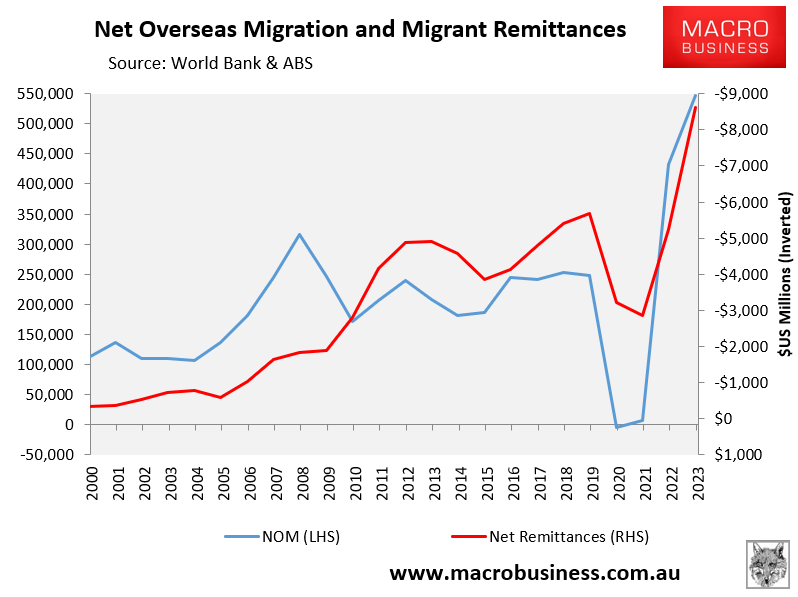

The net outflow of migrant remittances has also paralleled the rise in net overseas migration (students):

As net overseas migration (students) rose, so did the outflow of migrant remittances.

The truth is that a significant chunk of Australian expenditure by international students is funded by them working locally.

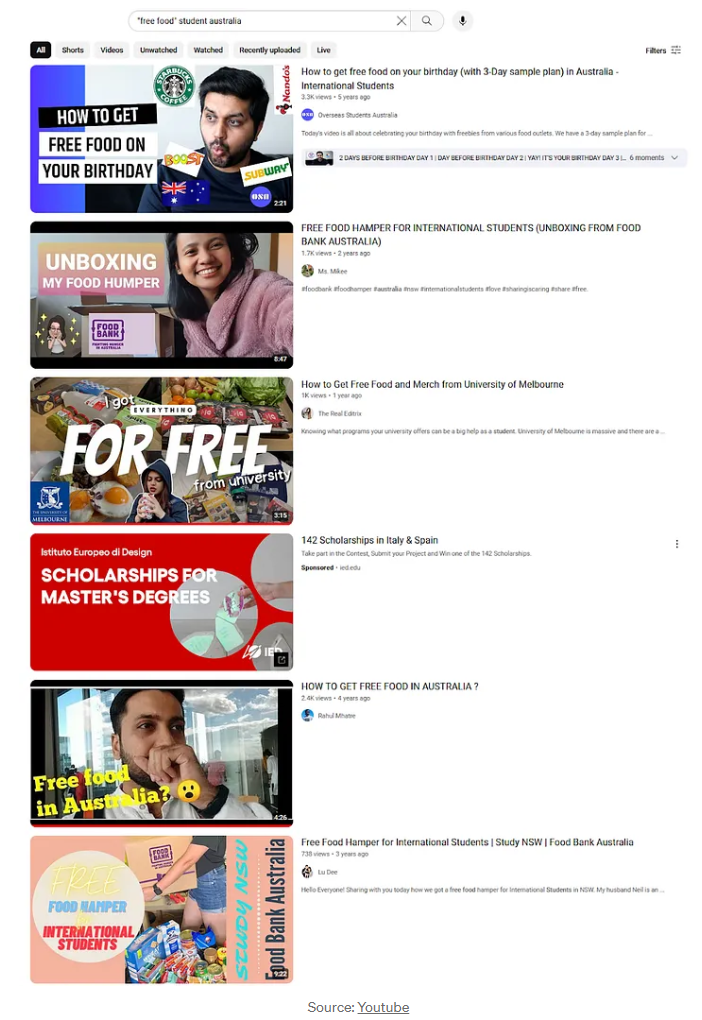

In his recent magnum opus on Australia’s political economy, Matt Barrie noted that “YouTube and Tiktok are full of videos from international students explaining how to rort free food out of the system:

“I’m not sure why we’re providing visas for international students who can’t afford to feed themselves”, Barrie said.

“This is supposed to be an “export” not a humanitarian program”.

Last year, the Herald-Sun reported that demand for free food services and food banks had soared across Melbourne’s universities, with 85% of this demand coming from international students.

“We can grab five basic items, such as rice, milk, pasta, tomato sauce, soup – it’s a lifesaver”, international student Krithika Venkatanath said, while admitting that she used the free food service most days.

“It’s so hard to juggle work and study, especially with the upfront costs and higher tuition fees for international students”, she said.

Recently, ACA ran the following report on the proliferation of people turning to food banks in Melbourne:

The reporter noted that “the line is full of students” before interviewing a foreign student who stated, “This [food bank] is good. This is very helpful for us for international students”.

On Tuesday, The SMH reported that “demand for the University of Sydney’s student-run food welfare service, FoodHub, which offers free food and essential items such as toiletries, rose 60% in the past year, with international students making up 93% of the 57,000 students who used the service in 2024”.

The queue for Sydney University’s food welfare service stretched well outside the door on Thursday. Almost all were international students.

“International students have also driven demand at UNSW’s student-run free food service, which feeds 1500 students each week, up from 150 when it opened in May 2020. In July, Western Sydney University started a service after a student survey found 50 per cent were food insecure”.

“Queues at the services can now stretch over an hour, with online booking systems used to ensure they do not run out of food”…

“Among the students relying on food welfare services is Shuyin Li, a 23-year-old master’s student who arrived in Sydney last year after completing her undergraduate course in her native China”…

“Li collects frozen and canned food each week, but also takes essential items such as toothpaste and tissue boxes”.

“Muhammad Hasnan Sazzad, a 34-year-old Bangladeshi PhD student, started attending UNSW’s food welfare service during the pandemic, when he and his wife were unable to keep a steady wage”.

While we sympathise with their plight, what good is having international education “exports” who are the working poor?

These students must work to cover their living expenses, compete with younger Australians for jobs and relyfull-timeAn increasing on charitable services to make ends meet.

When international students become a drain on charitable services, you know that the economic and human value to Australia has turned negative.