The lunatic RBA is back. It was a label I used for years before COVID as the central bank was far too tight for too long.

Inflation in Australia is collapsing. It’s going to keep doing so on every measure.

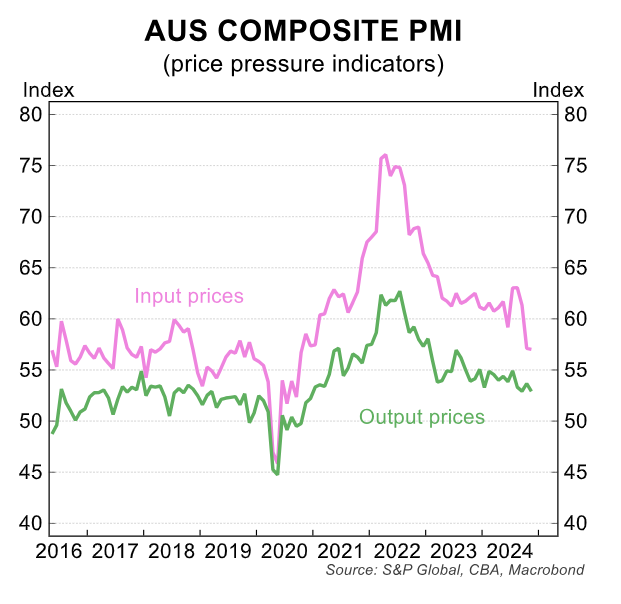

Input and output prices are already back in the lowflation range.

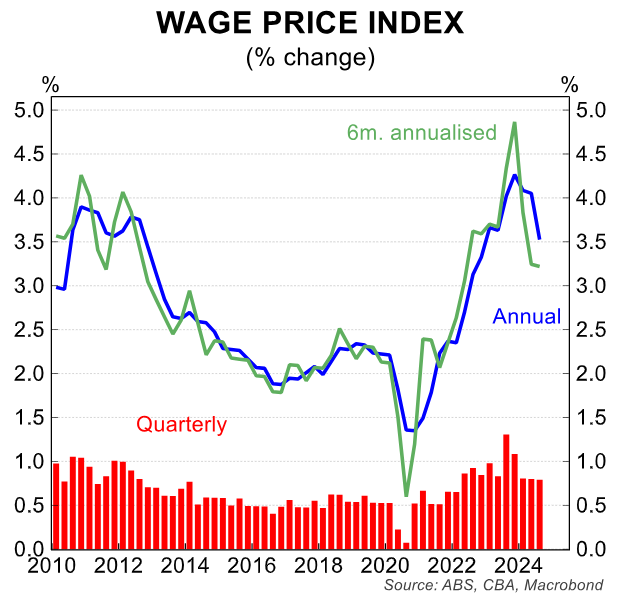

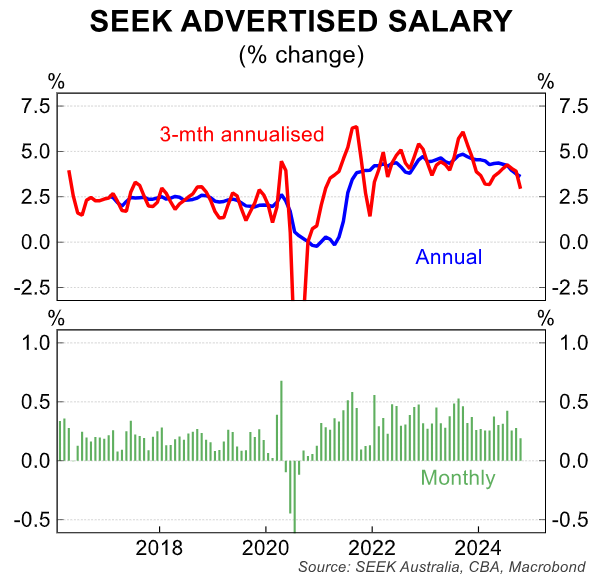

Moreover, inflation is being led lower by crashing wage growth.

This is particularly important for the RBA because it trashes its reasoning for keeping interest rates tight.

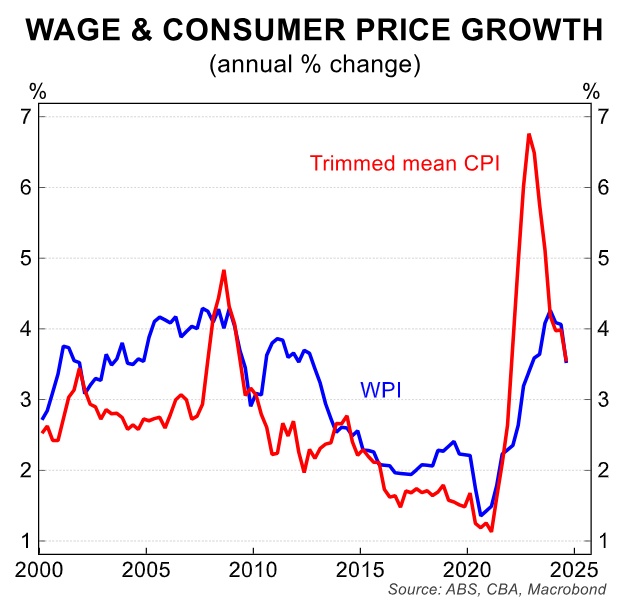

The RBA has gone to great lengths to explain that weak productivity and a positive output gap (by its measure) are going to keep wages and inflation strong.

This is poppycock, based upon a theoretical economy that does not exist today.

Australian growth is led by immigration and labour market expansion.

Such an economic model supplies its own labour in a permanent supply shock. There is no pressure on wages. Ever.

Australian wage growth has been stuck at 3.2% for nine months, a level consistent with 2.5% inflation.

And the leading indicators are pointing lower, not higher.

Second, weak productivity doesn’t lift inflation in a labour-market-led growth economy because population growth delivers profits without the need to lift prices.

Third, the stickiest part of Australia’s inflation is services. And labour-centric services are the area of the economy most impacted by wage growth.

So, falling wage growth means falling inflation.

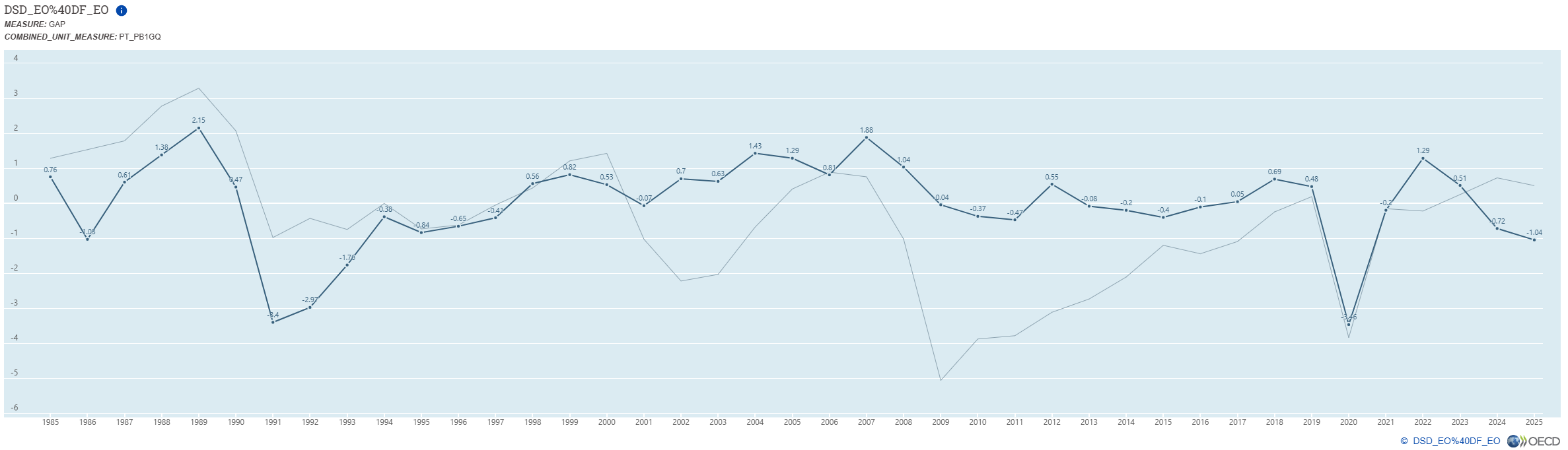

Fourth, alternative output gap measures, like that of the OECD, are much more consistent with falling inflation than the RBA’s dodgy version, which has again missed the turn in wages.

OECD measures are overshooting into the negative, where economic slack kills all prices (the narrow line is the US for comparison, which is already cutting rates).

The Bullock RBA has gone out of its way to apply these concepts to avoid making the mistakes of the Lowe administration, which couldn’t forecast its way out of a wet paper bag.

Productivity was cheered on under the Stevens and Lowe RBA’s but it was never central to setting the cash rate. The output gap was never mentioned.

However, the Bullock RBA has shifted its reaction function too far.

Productivity is a structural issue. Arguably so is the output gap in an immigration-led economy. Monetary policy is cyclical.

The Bullock RBA appears to be so punch-drunk by past failures of forecasting that its confidence in itself has collapsed, and it will only shift policy when deeply backward-looking data meets its targets.

Gareth Aird at CBA points out that:

The November RBA Board Minutes noted, “it is important to remain forward looking, avoiding an excessive reliance on backward-looking information that might lead the Board to react too late to a change in economic conditions”.

But we struggle to reconcile that statement with the line from the Minutes that in response to a scenario where inflation fell more quickly, “this could warrant an easing in the cash rate target, but that they (i.e. members) would need to observe more than one good quarterly inflation outcome to be confident that such a decline in inflation was sustainable”.

The policy setting process cannot be forward looking if the Board is on a predetermined path to wait for more than one ‘good’ quarterly CPI before being willing to commence the process of normalising the cash rate. Inflation is a lagging indicator, notwithstanding too the publication lag given the quarterly frequency.

Such reduced volatility in the cash rate only ensures greater volatility in the economy.

And further embarrassment for a fatefully stupid RBA.