The war of words between the Albanese government and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) over inflation and interest rates is heating up.

Following last week’s decline in headline CPI, Treasurer Jim Chalmers celebrated that inflation was now within the RBA’s target range.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese told a business dinner on Wednesday that inflation is falling, citing the headline inflation rate.

“The inflation figures tell that story. Two years ago, annual inflation had a 6 in front of it and was rising. Today, it has a 2 in front of it, and it’s falling”, Albanese said.

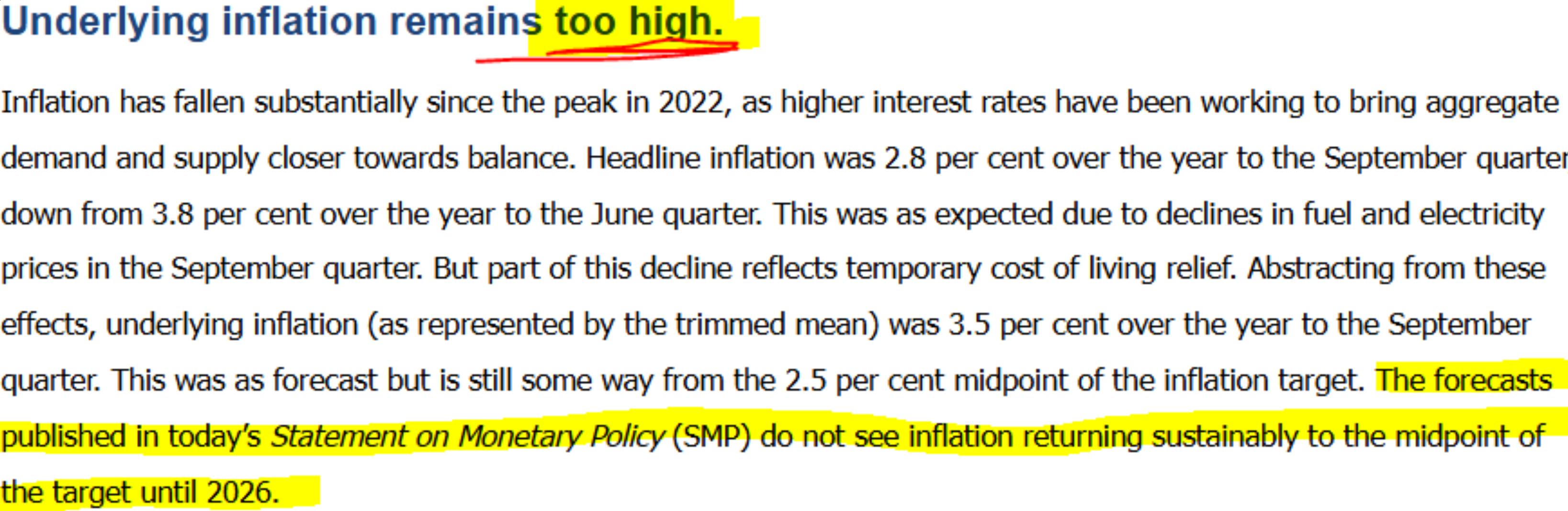

However, Tuesday’s monetary policy media release from the RBA noted that “underlying inflation remains too high” at 3.5%:

The release also noted that “growth in aggregate consumer demand” has remained “resilient” due to “spending by temporary residents such as students and tourists”.

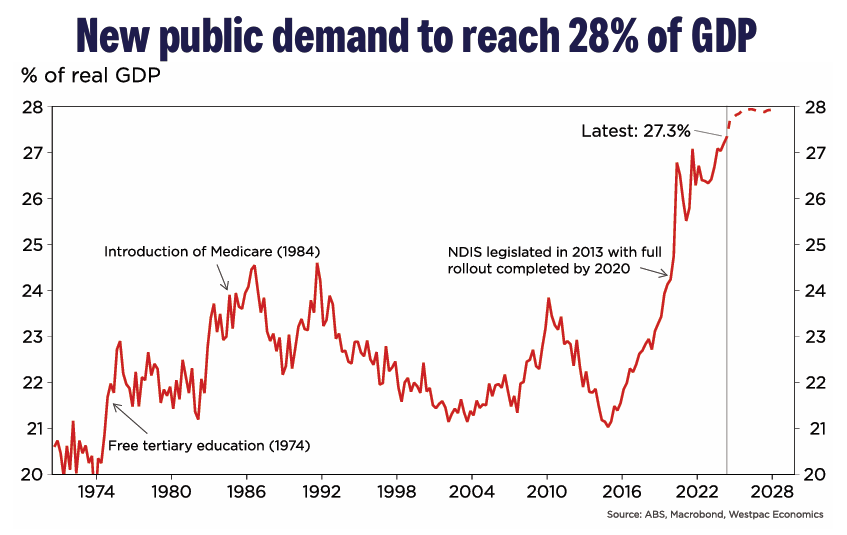

In her press conference following Tuesday’s monetary policy meeting, RBA governor Michele Bullock admitted that the Bank had been blindsided by record public spending, which has inflated aggregate demand and kept unemployment low.

“It’s not just the federal government, it’s the state governments as well”, Bullock said.

“The fact that we’ve had to revise up our public demand forecasts, it’s reflected the fact that there’s been more announcements and more things going on”.

This follows the RBA’s comments in August noting that the growth in government spending was one of the reasons it no longer expected underlying inflation to return to target until mid-2026.

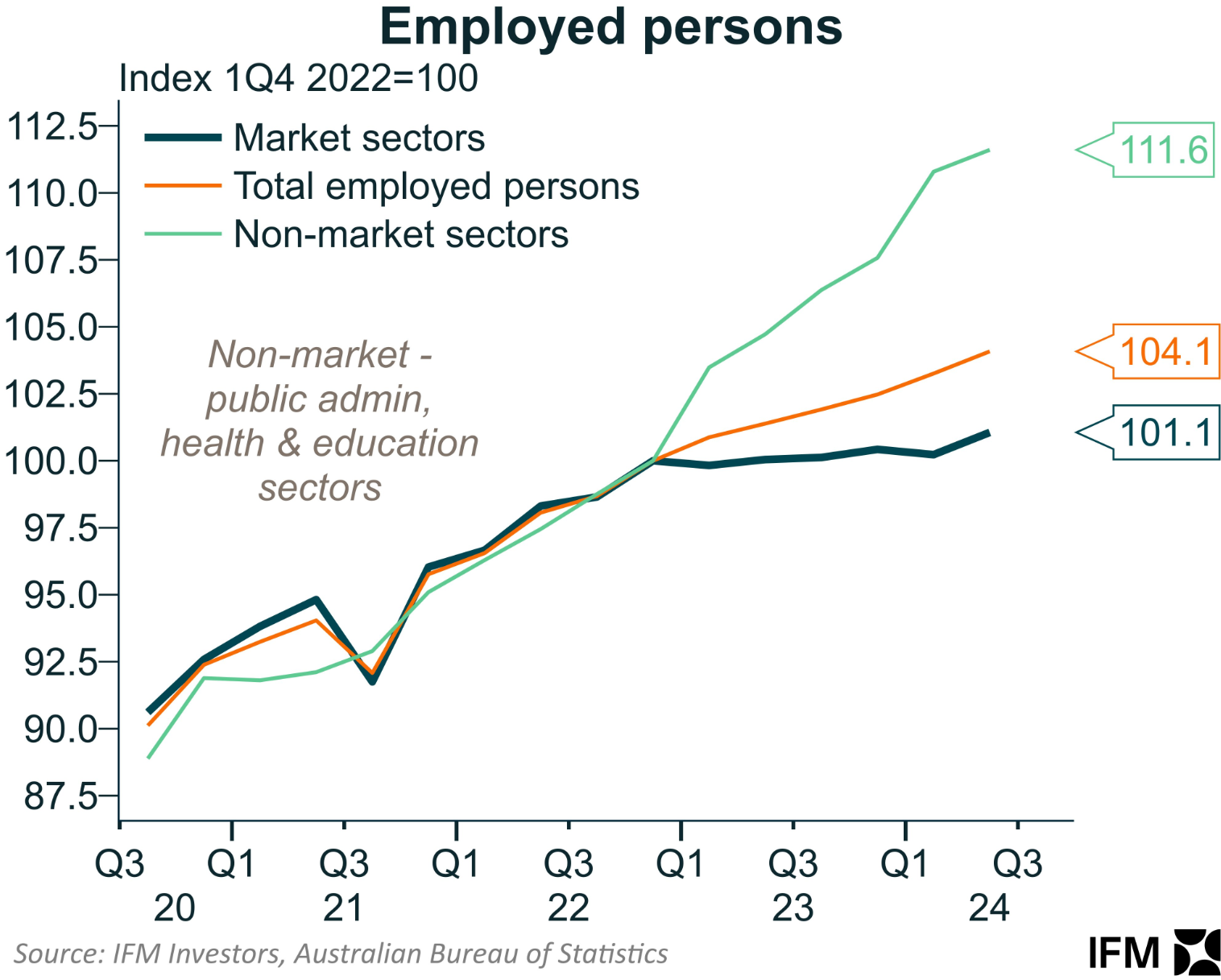

Nothing sums up the situation better than the following chart from Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Investors:

Since Q1 2022, just before the Albanese government came to office, overall employment across the Australian economy has grown by 4.1%.

Nearly all of this job growth has come from the non-market (government-aligned) sector, where the number of jobs has expanded by an extraordinary 11.6%.

In comparison, job growth across Australia’s market sector has stagnated, growing by only 1.1% over the same time period.

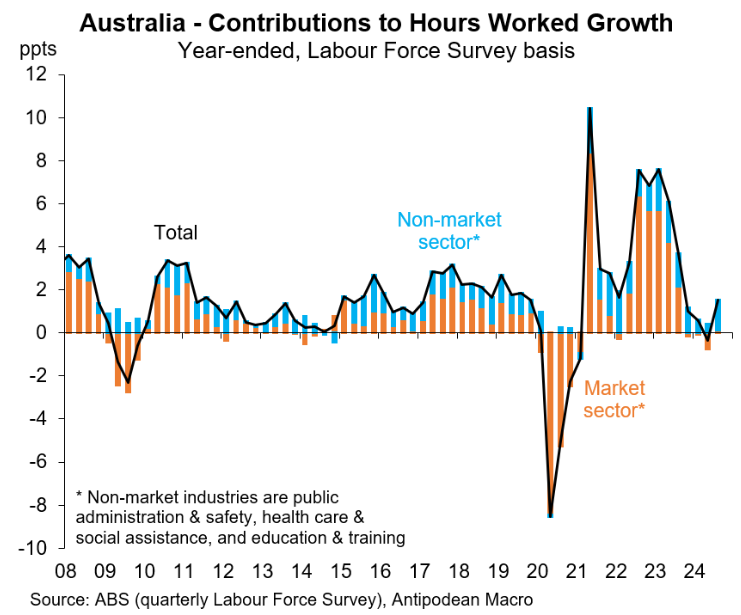

A similar story emerges with aggregate hours worked, where all of the 1.5% growth in hours worked in the year to September came from the non-market sector:

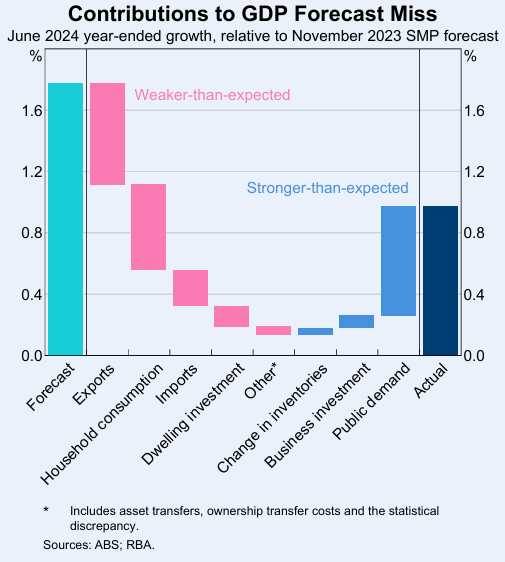

The impact of record public spending was reflected in the below chart from the RBA Statement of Monetary Policy, which showed that the growth in public spending was far stronger than anticipated.

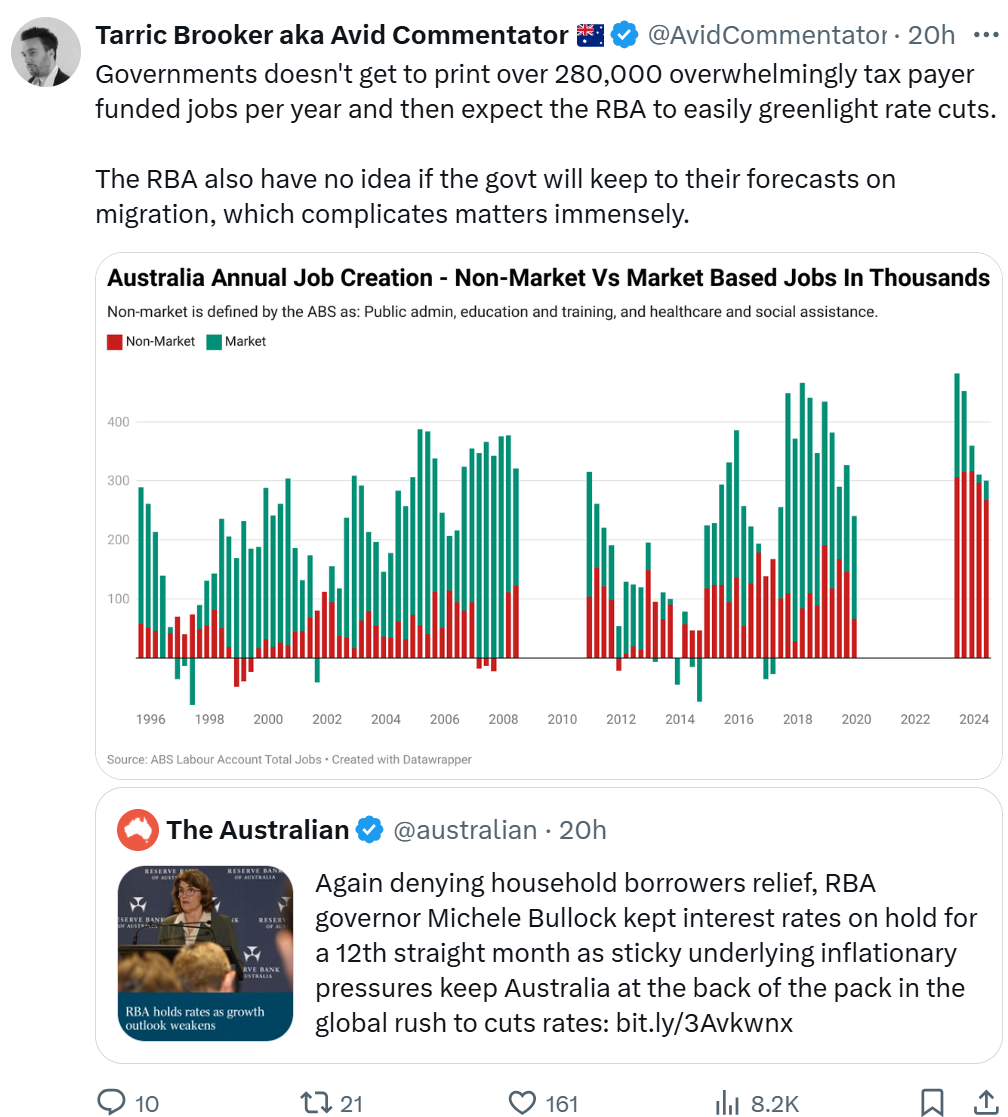

Independent economist Tarric Brooker summed up the situation nicely in the following Tweet:

It is a bit rich for the Albanese government to complain about inflation and interest rates when it has engaged in what Brooker terms “burnout economics”: pumping the demand accelerator via massive public spending and record immigration, while the RBA is trying to slow the economy via monetary tightening.

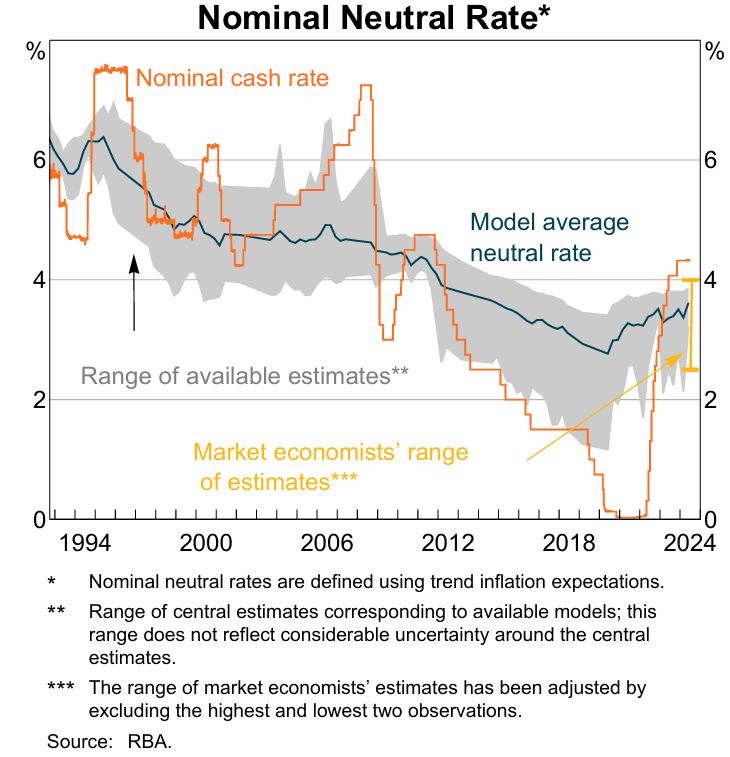

In any event, the RBA believes that monetary policy is only mildly restrictive, which means that interest rate cuts, when they arrive, will be fairly modest.