Anyone with half a brain knows that reducing the number of international students (and migration in general) will help to ease the rental crisis.

The association between the increase of international students and temporary migration is clear.

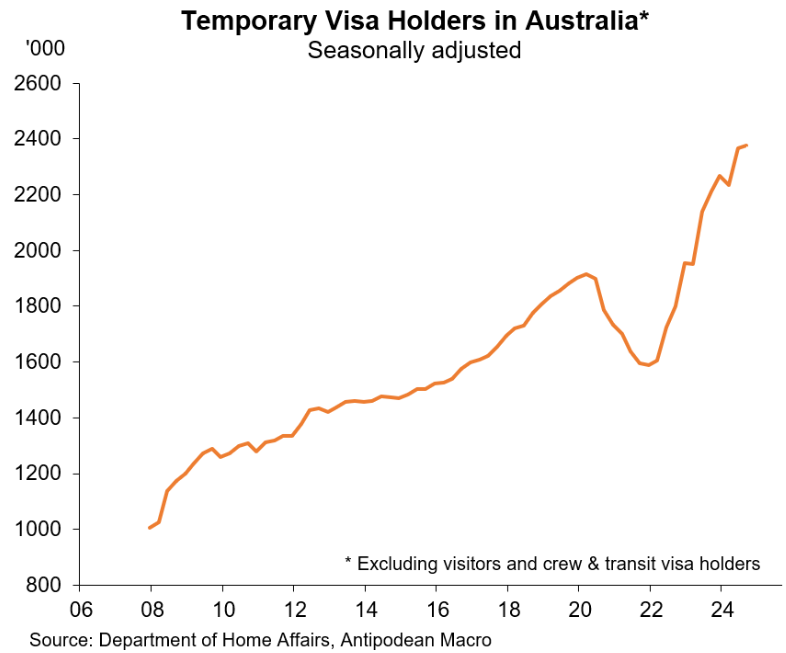

Temporary visa numbers in Australia have increased by around 500,000 over the pre-pandemic peak, as shown in the following chart from Justin Fabo of Antipodean Macro.

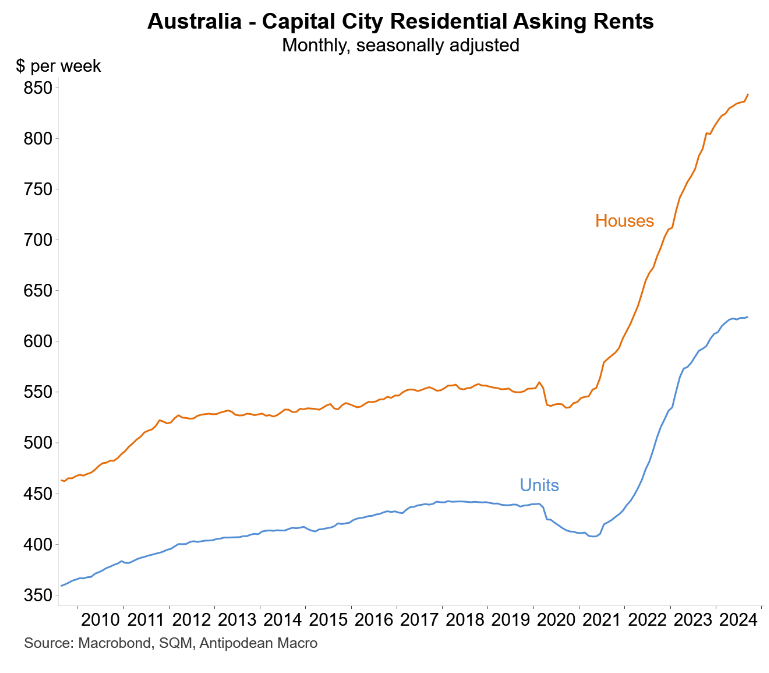

As expected, asking rents increased commensurably.

Importing an additional 500,000 renters, including via the international student pathway, will obviously increase the demand for rental housing.

Yet, there is no shortage of shills who claim that international student numbers and immigration more generally have little impact on the rental market.

Earlier this year, the Property Council of Australia’s student accommodation organisation, the Student Accommodation Council (SAC), released a propaganda report claiming that the record surge in international student numbers has had minimal impact on the rental market.

The SAC claimed that international students utilised only 4% of the nation’s rental housing stock.

The SAC’s report was officially debunked by a fact sheet from the Department of Education, which found that international students utilised 7% of Australia’s rental accommodation or one in every 14 rental homes:

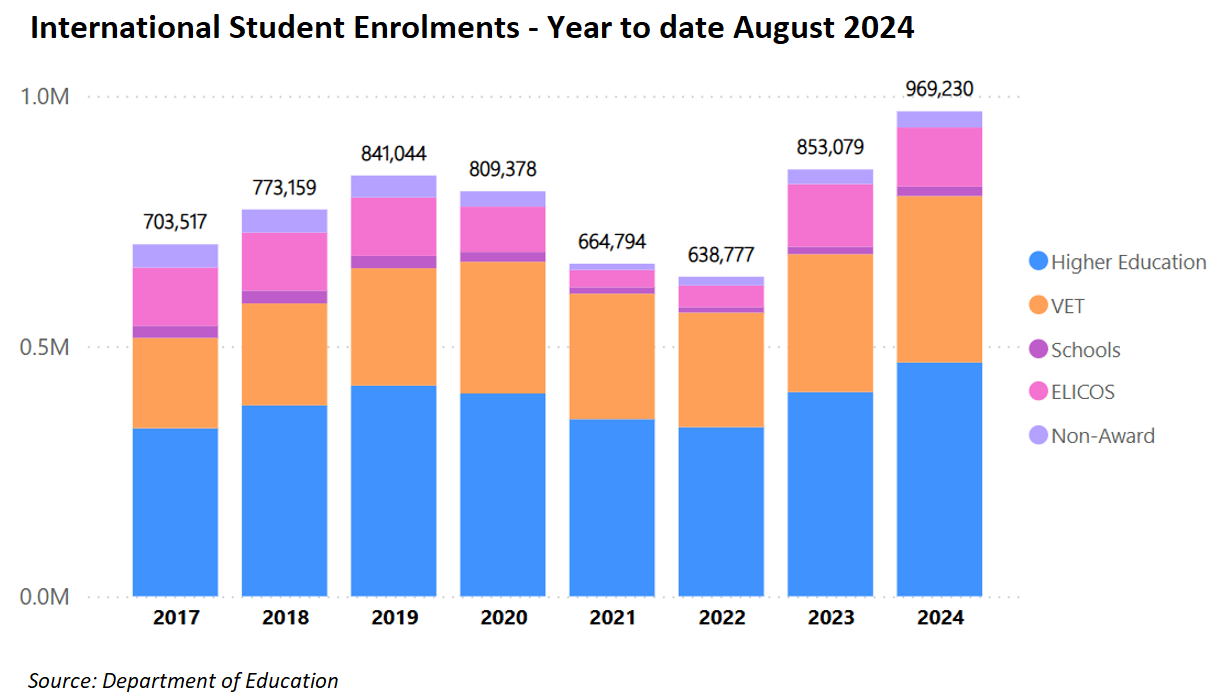

“The Department of Home Affairs Number of temporary visa holders in Australia report (BP0019), 31 July 2024, shows 696,162 student visa holders in Australia. This represents a 91.3% increase in the number of student visa holders when compared to the 2021 census data from which the 4% figure was derived”.

“All other things being equal, this means that the 4% national average figure based on the census would be more like 7% based on 31 July 2024 figures”, the Department of Education estimates.

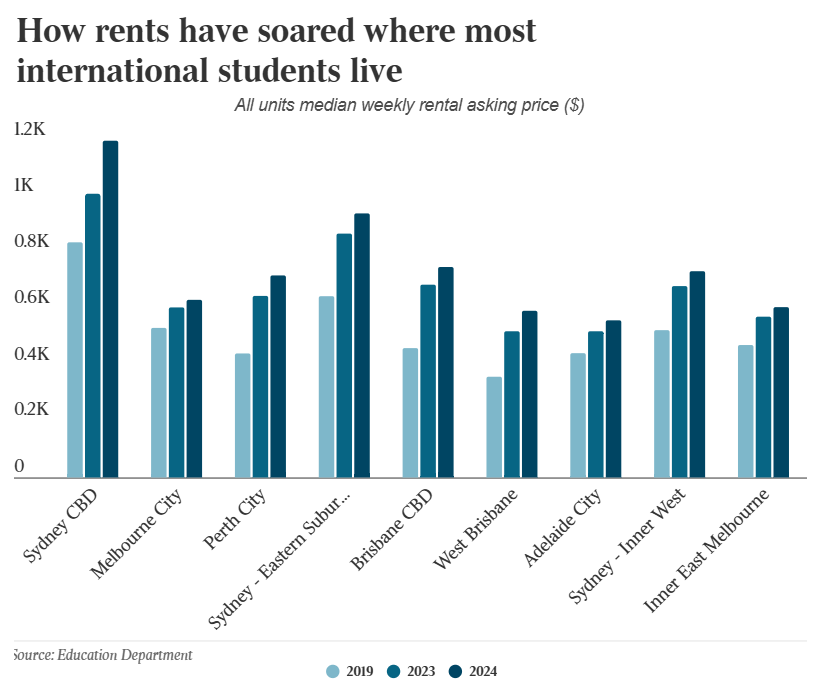

The fact sheet notes that the 7% figure was a national average across all rental markets and that the concentration is much higher in major capital city areas:

The Department of Education also explained how the surge in international students has very likely driven up rents:

“The Reserve Bank of Australia estimated that a 1% increase in dwelling stock results in the cost of rentals decreasing by 2.5%”.

“A 1% reduction in the demand for private rental properties has an equivalent impact as a 1% increase in dwelling stock and would result in a decrease of rental prices across the market, especially in inner-cities”.

The SAC has returned with more propaganda, claiming that capping international student numbers and migration more generally is an ineffective way of easing rents and will harm the economy.

“It’s not the fault of international students. Migration and natural population growth are factors on the demand side, but not the sole demand factor”, Torie Brown, executive director of the Student Accommodation Council said.

“A shift to smaller households, the rise of one person dwellings, the increase in people using their spare bedrooms for home offices instead of as a share house or a flatmate, the rise in Airbnb has also had an impact”.

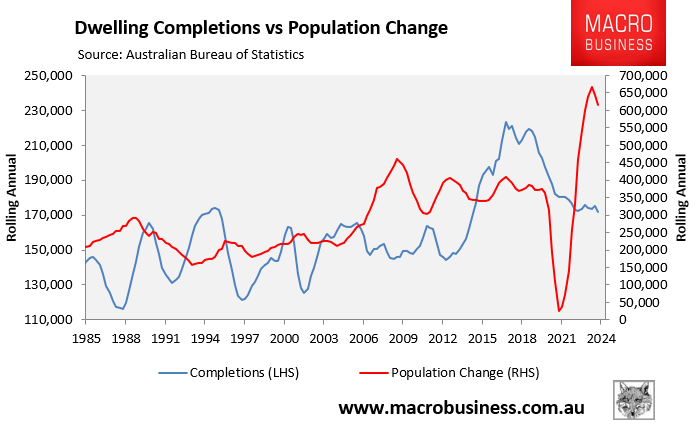

The SAC can gaslight all they like. However, it will not change the facts: housing demand via immigration-driven population growth is running way ahead of supply.

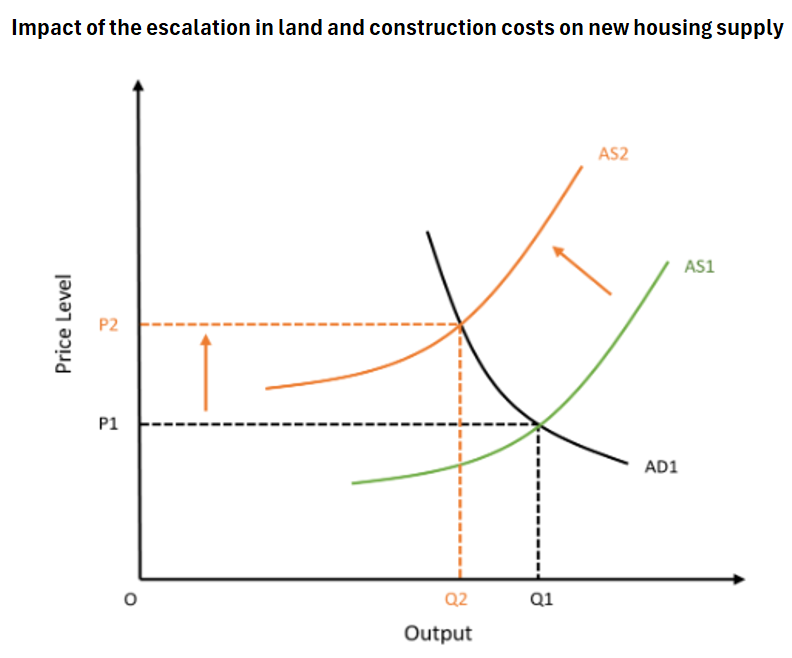

A number of factors that are likely to persist have hampered the supply side of the housing market, including:

- Structurally higher interest rates.

- Structurally higher construction costs, following a ~40% increase in costs post-pandemic.

- A reduction in the number of home builders available to build homes following a wave of insolvencies.

- A structural reduction in labour in the homebuilding industry due to poaching from government big build infrastructure projects.

These factors have effectively shifted the supply curve for building homes to the left, reducing capacity and making it more expensive at every price point.

Given that the supply side of the housing market has been structurally hampered, a commensurate reduction in demand is required to balance the market out.

This necessarily requires a reduction in international student numbers and immigration more generally.

Otherwise, the housing crisis will become permanent.