By Stephen Saunders

Stabilising population, argues the report Big thirsty Australia, is the safest and cheapest avenue to meet arid Australia’s water needs. It’s not what government wants to hear, is it?

Our water (and urban) planners are whizzes at supply-side solutions. But they don’t engage meaningfully with the population-demand side. That’s not our department, mate.

Shouldn’t rampant population demand fit in with limited and heavily exploited water resources? No, Down Under, it works the other way around.

In eight informative chapters, this Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) report attempts to put P-for-population back into the water-planning equation:

“[Treasury] assumptions of water abundance are dangerously flawed. Expanded desalination, rather than being a solution, is a further symptom…

Constant expansion of water infrastructure to accommodate population increase is a costly exercise in running to stand still… stable population would be by far the cheapest way to meet Australia’s water requirements…

The fatalistic acceptance of official population projections has meant there is a population blind spot in Australia’s water planning.”

Big Thirsty Australia

First, the report checks water-extraction cultures and customs, from indigenous times to the present. Then fondly recalls that Peter Cullen died 2008.

He was an endangered species among our water scientists, linking “water deficits” to “rampant population growth.”

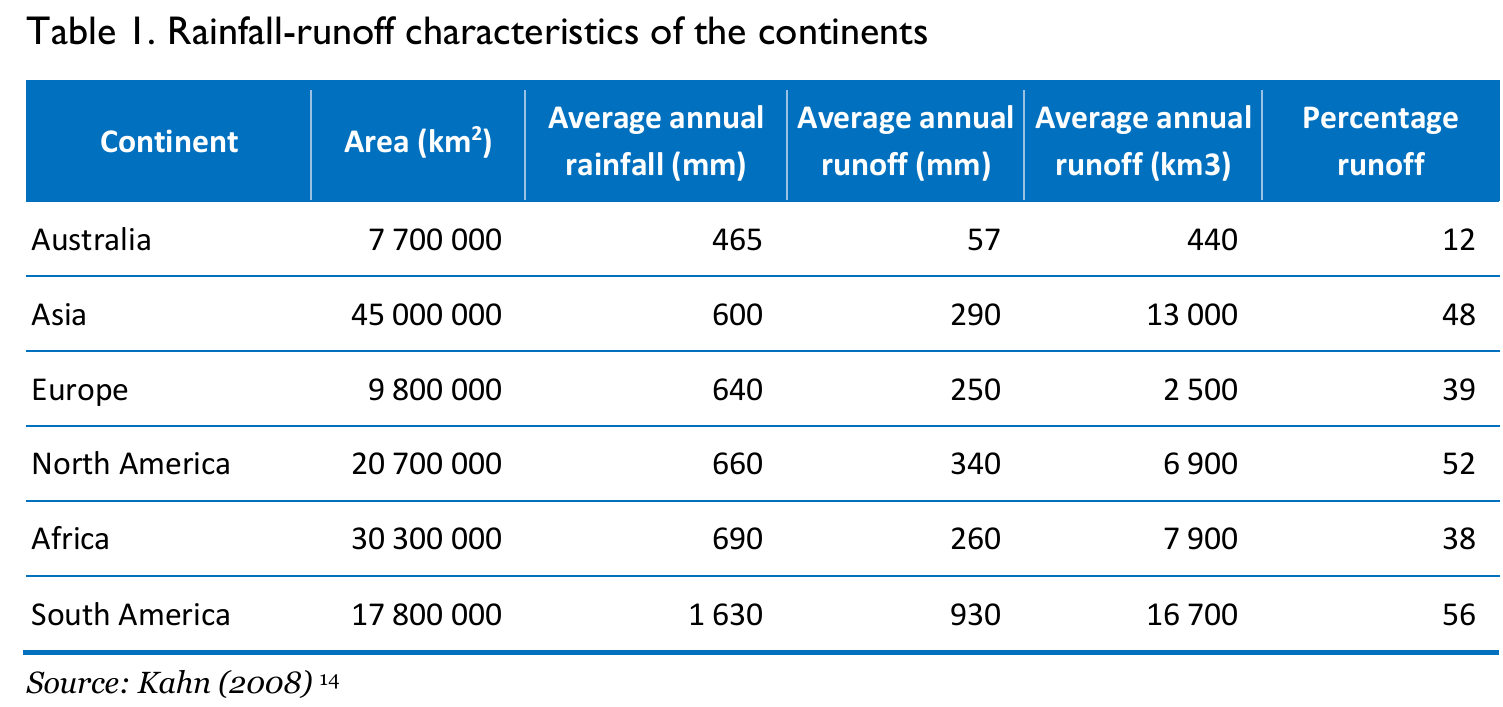

It’s not just the low rainfall; it’s also low runoff—12% of rainfall compared with 40-50% on other continents.

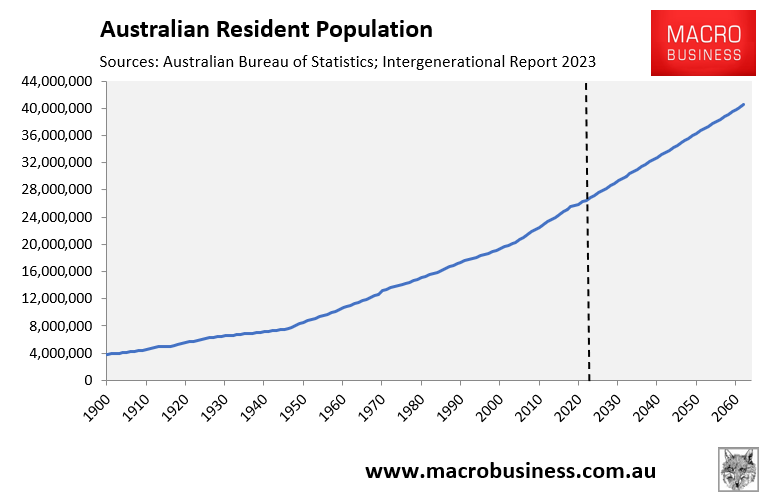

Yet population growth skyrocketed after 2000, hitting 2.5% annual growth in 2023. At 27 million, the population is suddenly eight million higher.

“Whether a town or city has enough water to meet added demand is not considered.” Assuming, proliferating desal plants can re-secure the system.

Though the Millennium Drought triggered “reform” in the Murray Darling Basin (MDB), the MDB Plan has yet to deliver the goods for traditional owners or others.

“Sustainable” water security

Be wary, cautions SPA, of “sustainable” water claims.

Aussie water planning operates on weak sustainability. “A sliding scale where ecosystems can be incrementally diminished to accommodate the imperatives of forever growth.” In pub parlance, she’ll be right.

It should be strong sustainability, “to prevent further loss of natural habitats and ecosystem functions”.

Stretched water resources

Half of Australia gets less than 30 cm of rain annually. We’ve got much more variable rainfall and runoff than other continents. This century, average rainfalls have diminished in the well-populated southeast and southwest.

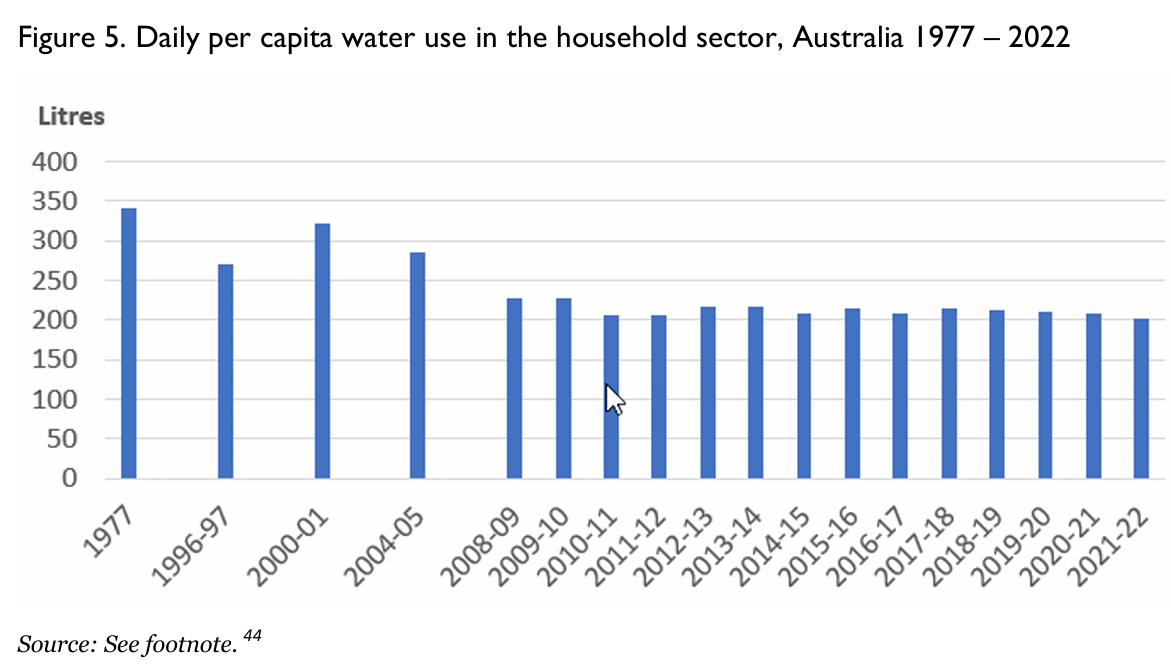

Easily our biggest water user is agriculture. Though the population has doubled since 1977, remarkably, aggregate water use is said to have “slightly reduced”.

Victory laps for irrigators and planners, eh? Problem is, we’ve hit the wall.

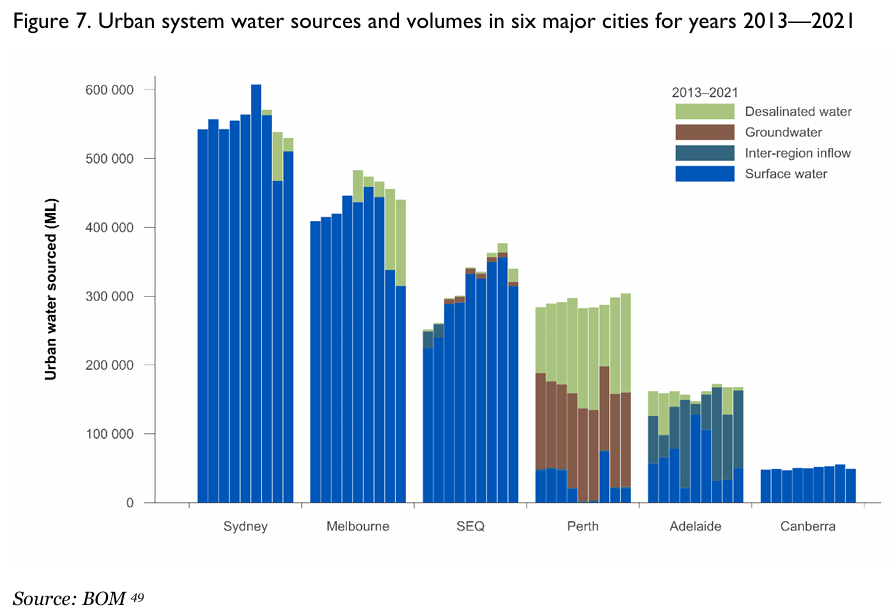

Household water-use efficiency has barely improved since 2010. Our top six cities still get nearly 60% of their take from surface water. But groundwater (25%) is increasingly stressed and overallocated, with heavier reliance on desal (12%).

The indirect water-consumption “footprints” of eastern-seaboard cities are 8–10 times higher than what they use directly. If you doubled their present populations, MDB would struggle to feed them. At affordable prices, that is.

Climate and water supply

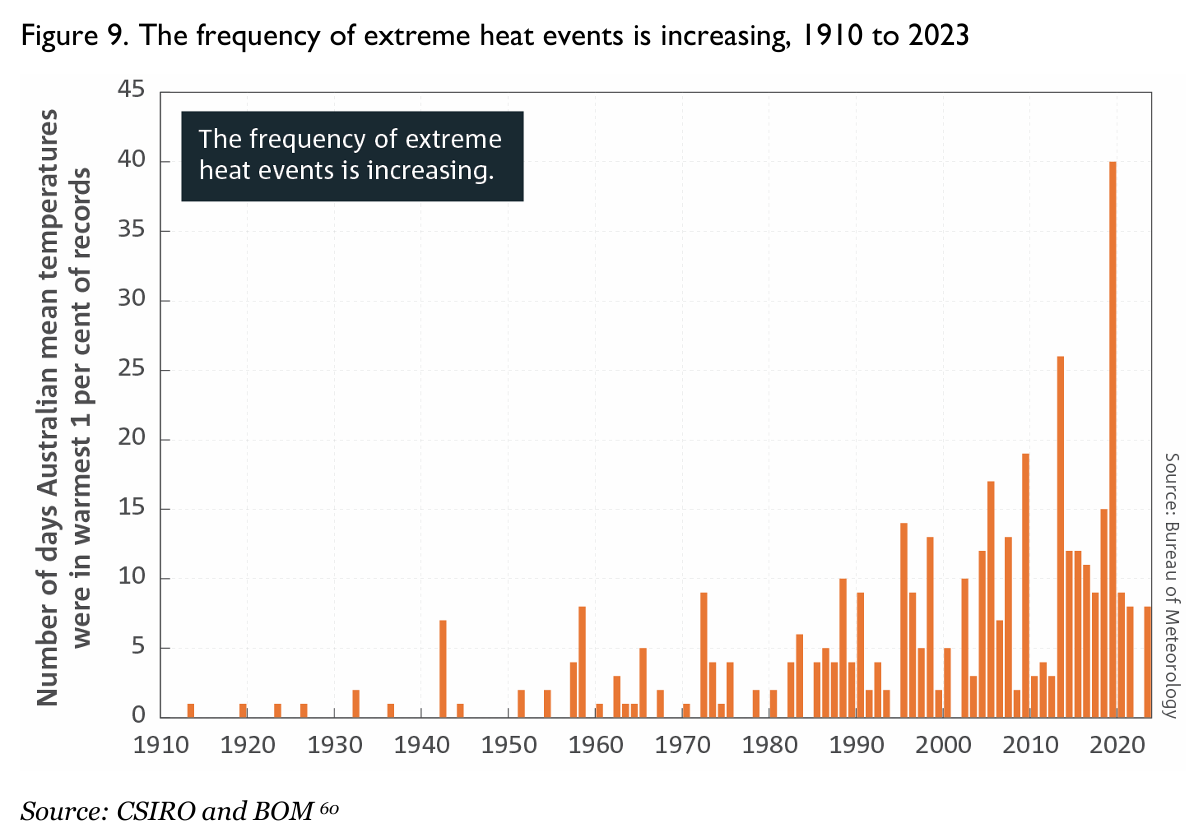

Australia is trending hotter and drier, with 2019 being the driest year on record. Inflows into west-coast dams and east-coast Murray River are declining. Extreme heat and rain events are increasing.

“Droughts, flood, and bushfires” damage soil, vegetation, and catchment water quality. With few viable sites left, building extra dams won’t cut it. Many regional towns have already experienced severe water shortages.

Comparing with our 2000-year paleoclimates, the 20th Century looks “wettish” and Millennium Drought “moderate”. Australia endured mega-droughts, in these paleo times. Urban-rural water planning should take heed.

Increasing desal dependence

By 2000, urban water demand had reached the maximum that could be “reliably” supplied by “conventional” rainwater and groundwater. Significantly, no city deployed desal.

Now, we’ve got six plants in five states. Perth is particularly reliant on desal and groundwater.

Studies over 2010-16 found desal might be “better” than extra dams as a “long” term option. They didn’t factor in population growth.

Mainland capitals are “planning” to massively boost their water supplies over the coming decades. Brash Melbourne reckons it might hit 80% “manufactured” (desal, recycled, storm) water by 2070.

At 2020, dozens of NSW and Queensland towns had insecure water supplies. Of necessity, desal’s coming into play in regional WA and SA.

Desal cross-dresses as an environmentally “sustainable” and climate “resilient” adaptation for further population growth.

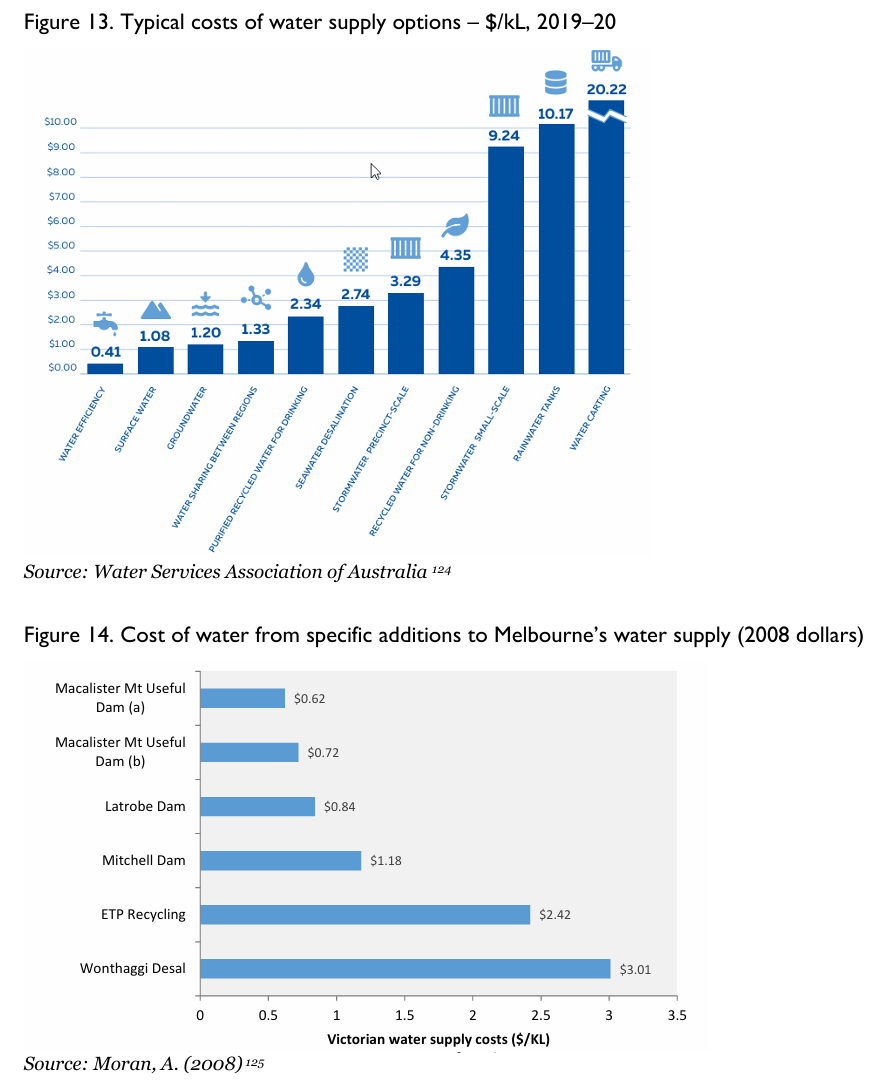

That’s playing down its punishing construction and running costs. It is much dearer than “conventional” water extraction, with consumers footing the bill.

What if costly desal somehow enabled an extra 13 million (largely imported) punters to camp out on our wilting landscapes? Maladaptive, contends SPA, not adaptive.

Stop ignoring population

Like a seasoned rugby pro, water-industry thinking sidesteps the population issue.

Water Services Association of Australia (WSAA, 2009) had us “well positioned” for population growth of any magnitude. A notable 2011 report said water wasn’t “a severe constraint” on population growth. Another (2018) said water-security risks could be “effectively managed”.

WSAA (2020) and the Productivity Commission (2020, 2024) are putting “all options on the table”. On the supply side, that is, not the population demand side.

Apparently, as “technical” specialists, water (and urban) planners feel obligated to appease “whatever” demand growth is forecast.

New water paradigm

“At the core of the techno-optimist mindset,” the report declares, “is a conviction that technology can treat symptoms rather than causes while continuing business as usual.”

Exhausting rain and groundwater, we’ve conjured a “diverse” water portfolio, including desal. Like housing, adequate water becomes less a right, more a commodity.

SPA urges a new ethos – water as a “commons not a commodity”. The so-called market won’t generate the right answers. Not with Big Australia up against a “heating, drying” climate.

“We have a choice about whether this growth continues”. The hell we do, retort Treasury overlords.

In conclusion, the report tags rapid population-growth as a “Faustian bargain”. Sacrificing voter wellbeing for “short term interests of an elite few”.

Compromised water-planning

The report could have said more about slack rural water planning and regulation. Aggregate usage of surface, ground, and floodwater resources is poorly measured and monitored.

Even along MDB river plains, a significant proportion isn’t metered, with casual theft and “mysterious” disappearances of huge volumes. Nonchalantly regulated floodplain “harvesting” is a persistent woe.

Rigged on to this creaking irrigation contraption is our 21st century MDB water market. It is delivering rather what you’d expect – prosperous marketers, if not necessarily farmers and communities.

Though SPA does question why state-local governments accept Treasury’s onerous population diktats. When they’re the ones who must deliver the infrastructure—and water.

I’d go further. Nearly all the key “stakeholders” are on the Treasury team.

Usually, I categorise them like this: Federal politics; federal agencies; states and cities; industry and developers; economists, planners and demographers; the media; universities and unions; think tanks and interest groups.

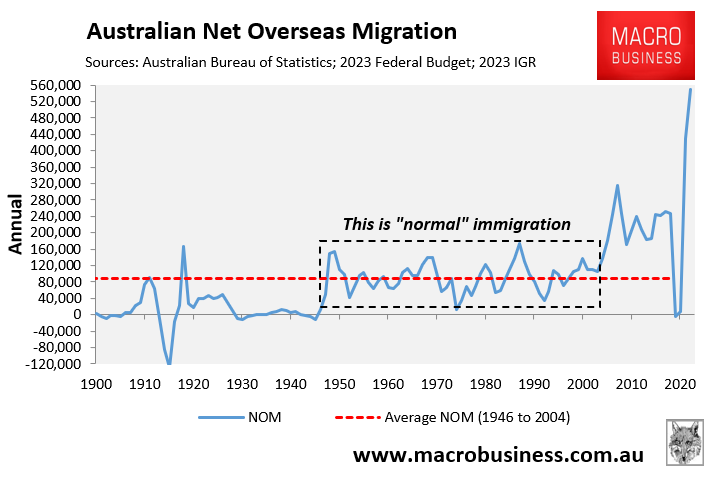

Among these, it’s not greatly controversial that this government’s heading for nearly 1.5 million in net migration over its three-year term. In a Big Thirsty, this ought to be highly controversial.

We’re thrashing the 2006-19 Big Australia years. Pulverising by a factor of six, the historical average from federation to date. Why doesn’t this perplex water-planners?

Like our climate-besotted urban planners, they’ve hobbled their own professionalism. Though very ingenious, they’re also embedded “influencers”, not always in a good way.

Check the Australian Water Association website. There’s no flashing light; that equitable water security is a forbidding mountain to climb on top of a steeply rising population.

Rather, they’re busy “connecting people…to inspire positive change…for a sustainable water future”. First up, the “diversity and inclusion” statement.

At WSAA, the new buzz is Nature Positive Water. “Net zero” and “circular economy” for vibrant water utilities. Never mind the population ballooning in the water catchments.

Then check out the Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists. Tey have gone woke since co-founder Cullen died.

Their 30-year Blueprint professes to fix water and the landscape. Set sail for “net zero”. Whilst waving through high population growth.

AWA, WSAA, Wentworth – they are climate techno optimists in full appeasement mode.

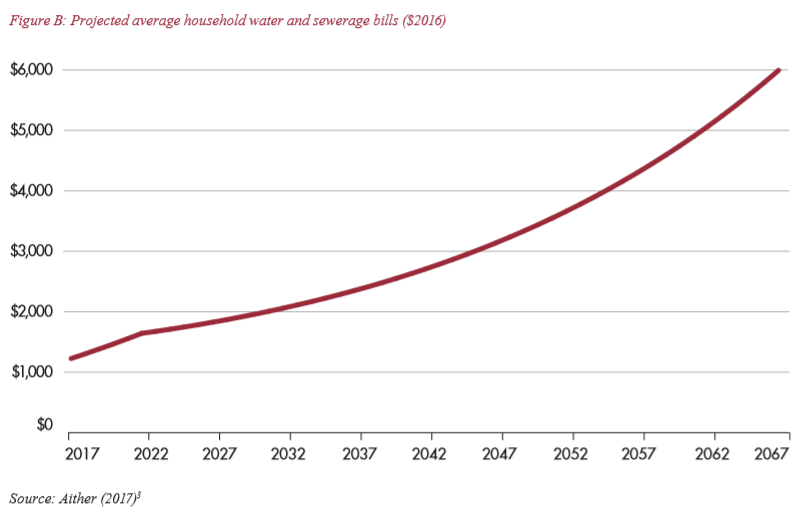

Good luck with that stance, guys. When water bills explode, it’s your Sydney Water taking the rap, not the Treasury.

Ominous water-futures

For decades, a handful of sterling agencies and individuals have tried to knock sense into the Aussie endless-growth environmental and population policy. Rude or respectful, none has stopped the rot.

For elite not voter welfare, arid Australia still insists on daft levels of population growth. This perpetuates damaging levels of housing and educational inequity and institutionalises costly, divisive, water insecurity.

Only a political unicorn (extraordinary leader, “natural” calamities, stakeholders themselves uprising) can begin to change that.

Should that unicorn ever materialise, our trendoid water-planning culture might have to recut its cloth for a parched continent’s escalating water liabilities.