My latest interview on Professor David Flint’s Save the Nation program explained why Australia’s productivity and living standards are declining.

The interview discusses a range of topics, including:

- The drivers of Australia’s poor productivity growth.

- Australia’s record per capita recession.

- Why Australia’s economy faces a low-growth future.

- The actual cause of Australia’s housing shortage.

Below is an edited extract of the productivity discussion.

The drivers of Australia’s poor productivity growth

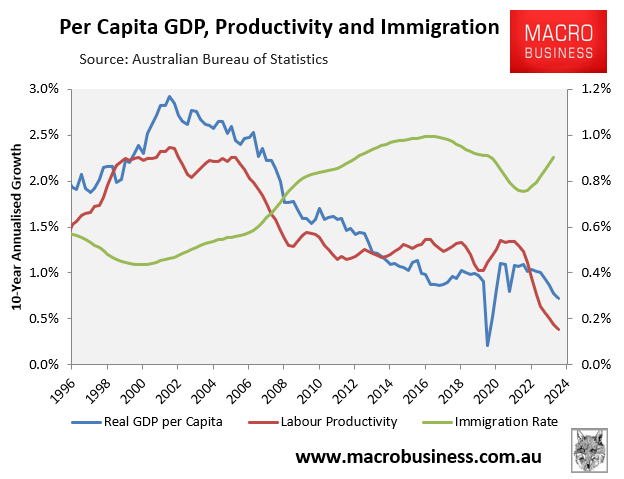

Australia’s labour productivity growth has fallen to 2016 levels.

Labour productivity measures how much output Australia produces per worker. And the amount of output per worker has actually fallen to 2016 levels. So we have gone backwards eight years in productivity terms.

Australia’s productivity growth has been falling since the mid-2000s. Labour productivity growth has fallen for the better part of 20 years and Australia’s per capita GDP growth has also fallen for about 20 years.

Interestingly, it coincides with Australia’s massively ramped-up immigration intake in the mid-2000s. The federal government has more than doubled Australia’s net overseas migration and has ratcheted up recently.

The harmful impact on productivity has come about through what economists call “capital shallowing”.

When a nation’s population grows faster than its business, infrastructure, and housing investment, it will deliver less capital per worker, which makes it less productive and reduces its per capita growth rate.

To give a real-world stylised example, imagine you run a cafe with one coffee machine and two staff members operating that machine and producing 100 coffees per hour.

If you double the number of staff operating that machine, so you have four staff, you are not going to double your output. Because those four staff will have to wait for each other to finish making their coffees, they will bump into each other, you will get congestion, etc.

Instead of producing 200 coffees per hour, which keeps your labour productivity constant, you’ll make, say, 150 coffees per hour.

Therefore, you have increased the number of people working but haven’t increased the capital stock—i.e., the number of coffee machines—to go with those people.

This means you can’t produce as many coffees per person and your labour productivity has declined.

This is effectively what the Australian economy has experienced for 20 years. We have grown the population aggressively—since 2000, Australia’s population has ballooned by 8.5 million—but we haven’t had the infrastructure, business investment, or housing to go along with that.

As a result, we have seen massive rises in congestion, less capital per worker, and ultimately lower productivity growth.

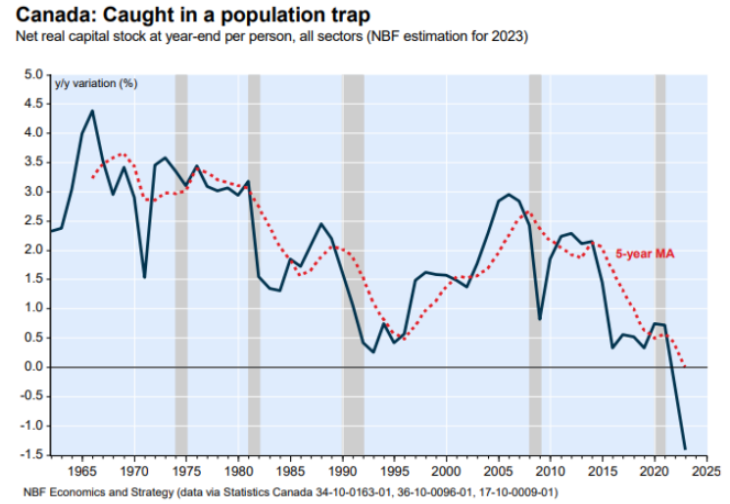

This capital shallowing has also happened in Canada as well. Canada has embarked on precisely the same policy.

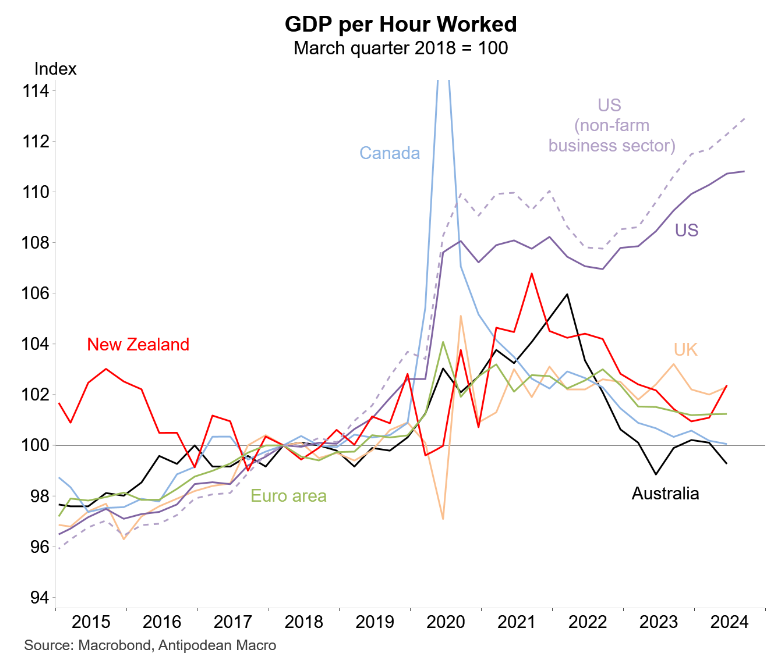

Canada has had a massive immigration boom and also has terrible labour productivity growth.

Both nations’ productivity growth has collapsed. They are both growing in an aggregate sense because of population growth, but per head, they are shrinking. And this is really a capital shallowing story.

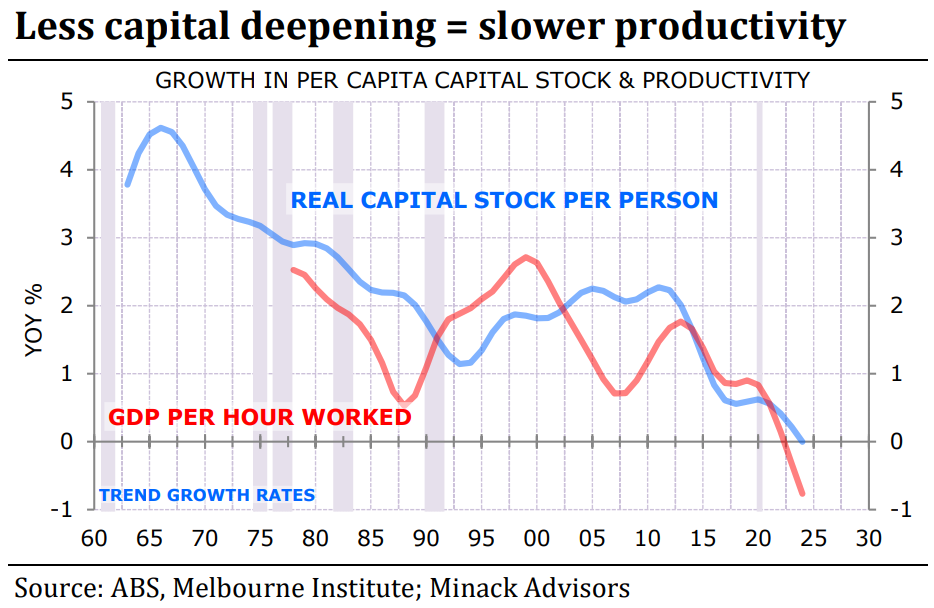

An excellent Australian economist named Gerard Minack, who is the former chief economist of Morgan Stanley and now runs his own advisory, has done a lot of research on this capital shallowing issue.

Minack has proven that Australia’s net capital investment as a share of GDP has crashed to around recessionary levels at the same time as we have grown our population aggressively.

As a result, Australia has diluted its capital stock and become less productive.

Australia has also diluted its enormous mineral wealth among more people.

Again, Australia’s population has ballooned by 8.5 million people this century. That is 8.5 million more people to share the nation’s mineral wealth among.

The lesson here is that if you grow your population too fast and you grow it faster than you can build infrastructure, business investment, and housing, you become poorer because you spread those things over more people and become less productive.

I wonder why more economists don’t discuss Australia’s capital shallowing problem. High immigration directly lowers Australia’s productivity growth via this capital-shallowing effect.