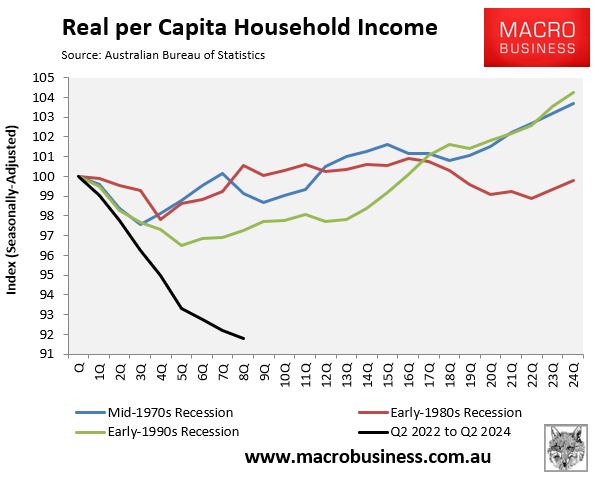

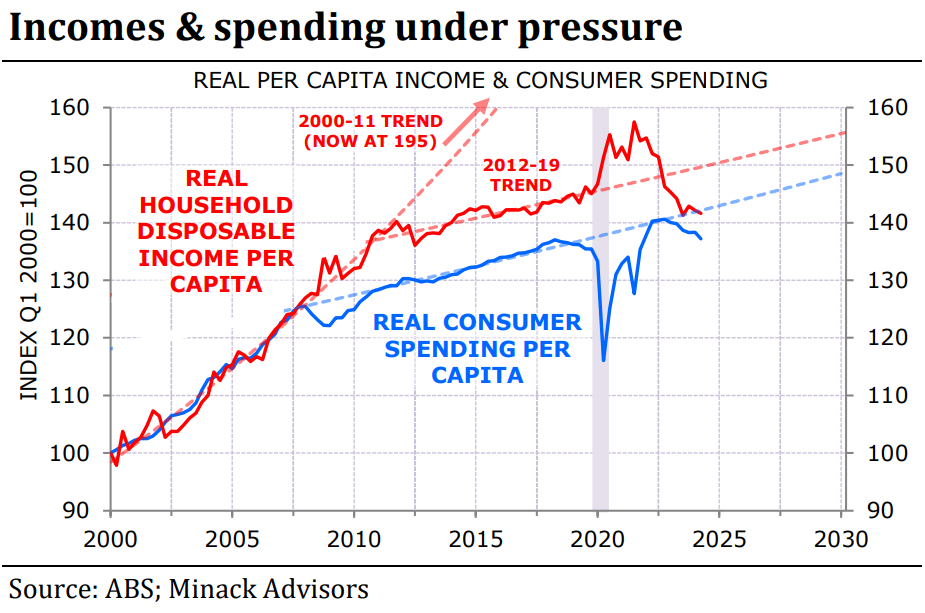

Australians are experiencing the sharpest decline in real household disposable incomes on record, as illustrated below.

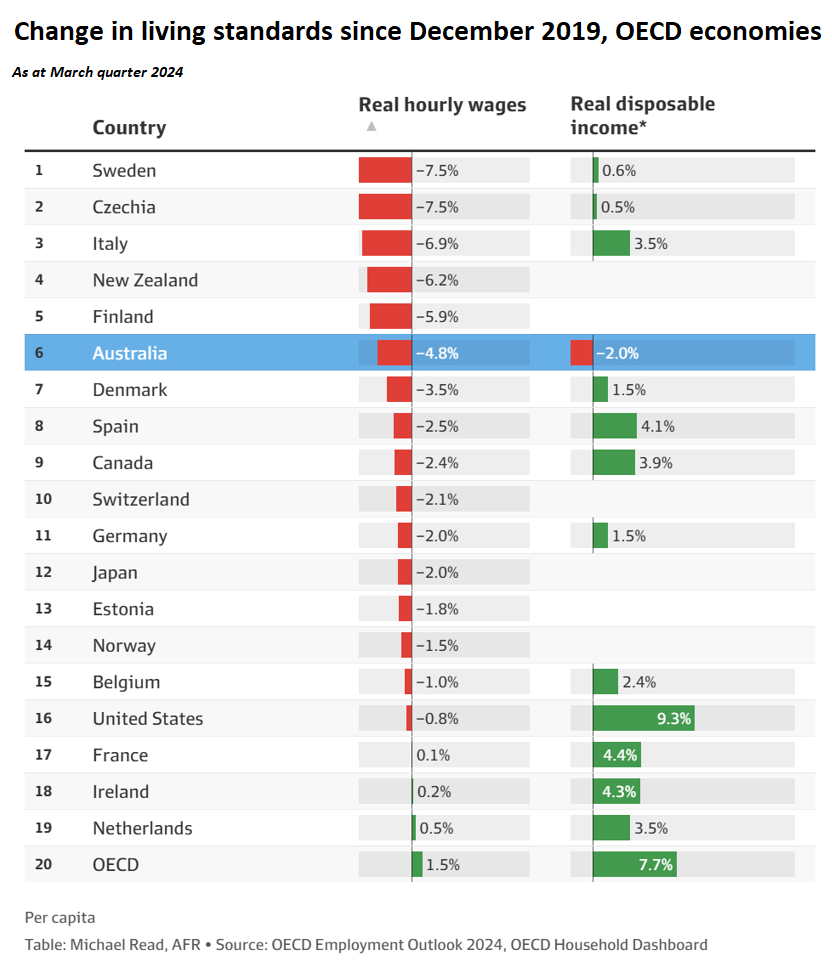

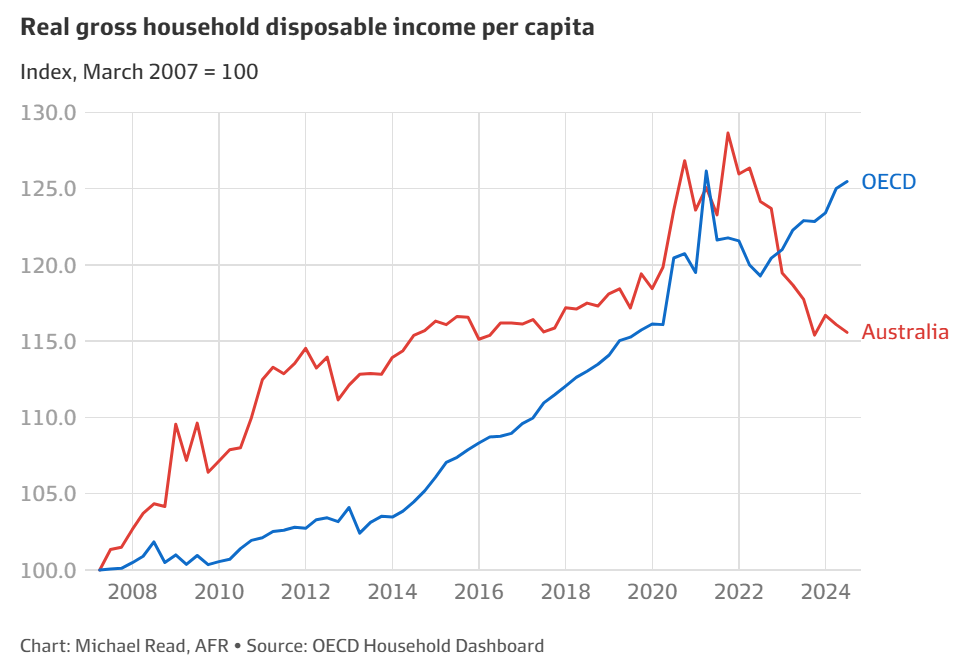

The AFR’s Michael Read published the following table showing that Australia experienced the largest decline in real per capita household disposable income in the OECD between Q4 2019 and Q1 2024.

Read notes that while Australia has experienced the sixth-largest decline in real wages, “Australians have experienced the sharpest decline in purchasing power across measured OECD economies over the past few years”.

“Disposable incomes are 2% lower than pre-pandemic levels in Australia, but 7.7% higher across the OECD”, noted Read.

There are three principal reasons why Australians have experienced the OECD’s sharpest decline in material living standards this decade.

First, as noted above, Australian real wages have grown at a slower pace than most OECD nations.

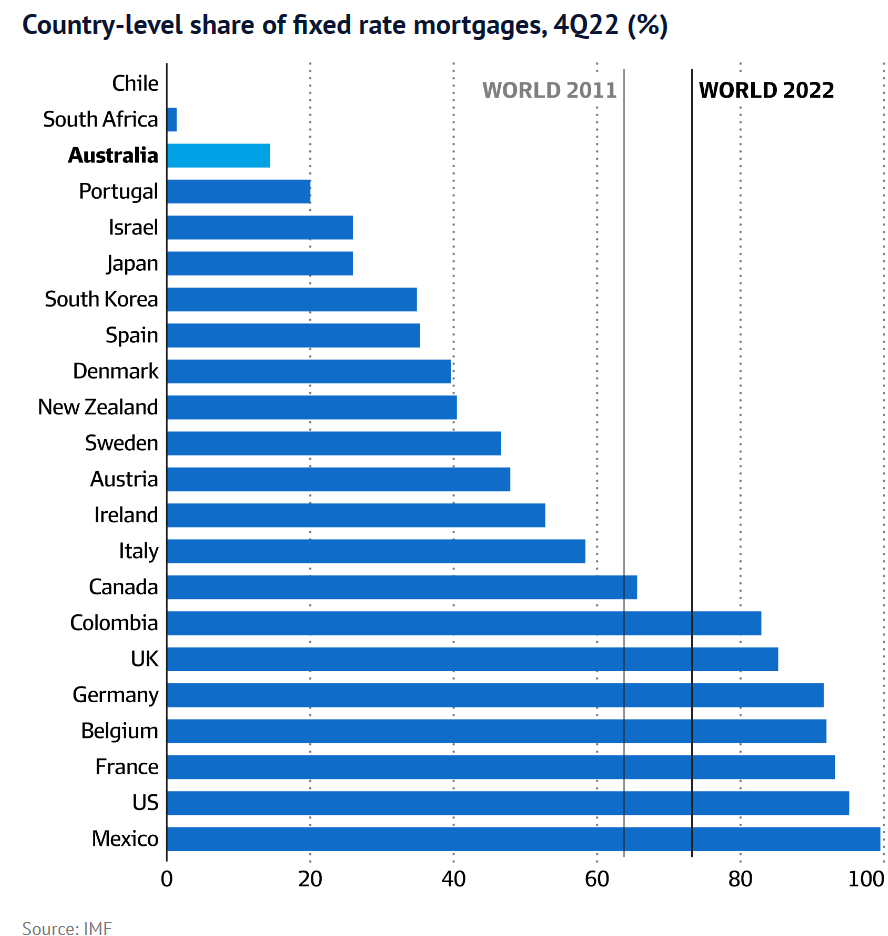

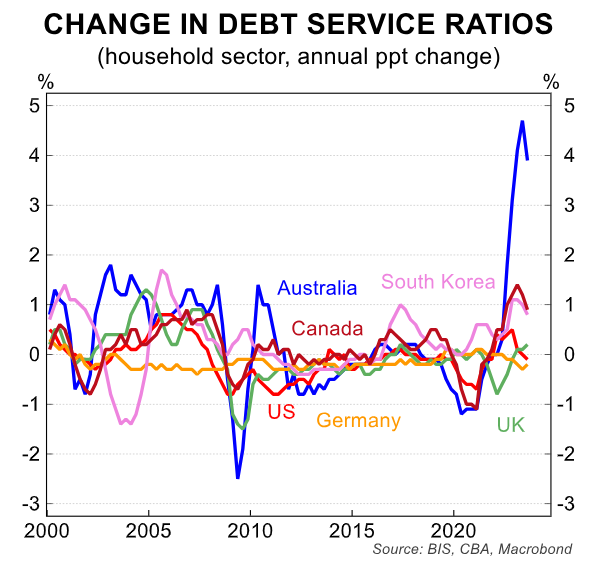

Second, Australia has one of the world’s highest shares of borrowers on variable mortgage rates.

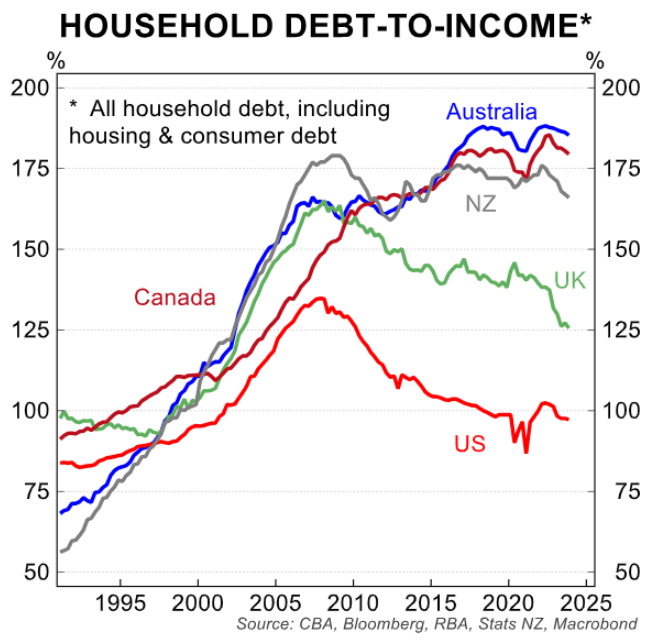

Australia’s household debt is also among the highest in the world.

Combined, these factors meant that Australian households were disproportionately impacted by the global rise in interest rates, reducing their disposable incomes.

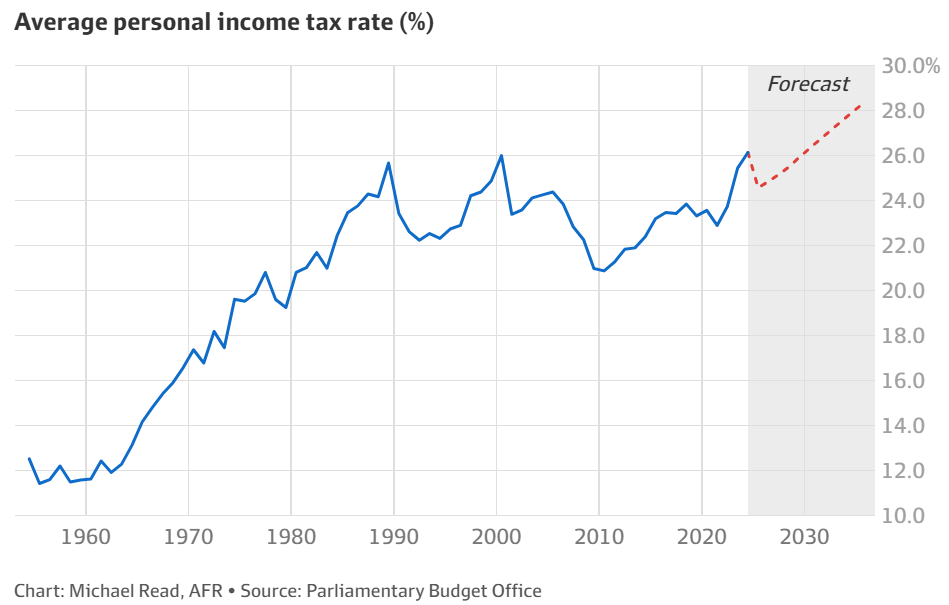

Finally, the combination of bracket creep (from inflation) and the expiry of the lower-middle-income tax offset lifted the average personal income tax rate to record highs.

This meant that Australian households took home less disposable income and the tax office took more.

The outlook for household disposable income is poor. While mortgage rates and inflation will inevitably fall, so too will wage growth.

As illustrated above, the share of income lost in taxes is also projected to rise.

Indeed, an analysis of the RBA’s forecasts in its statement on monetary policy for November suggests that real household income per capita will rise by only 1.3% in the current quarter, followed by growth of 1.2% in 2025 and 1.1% in 2026.

This would mean that Australians’ material living standards would still be 4.4% lower at the end of 2026 than at the time of the May 2022 federal election.

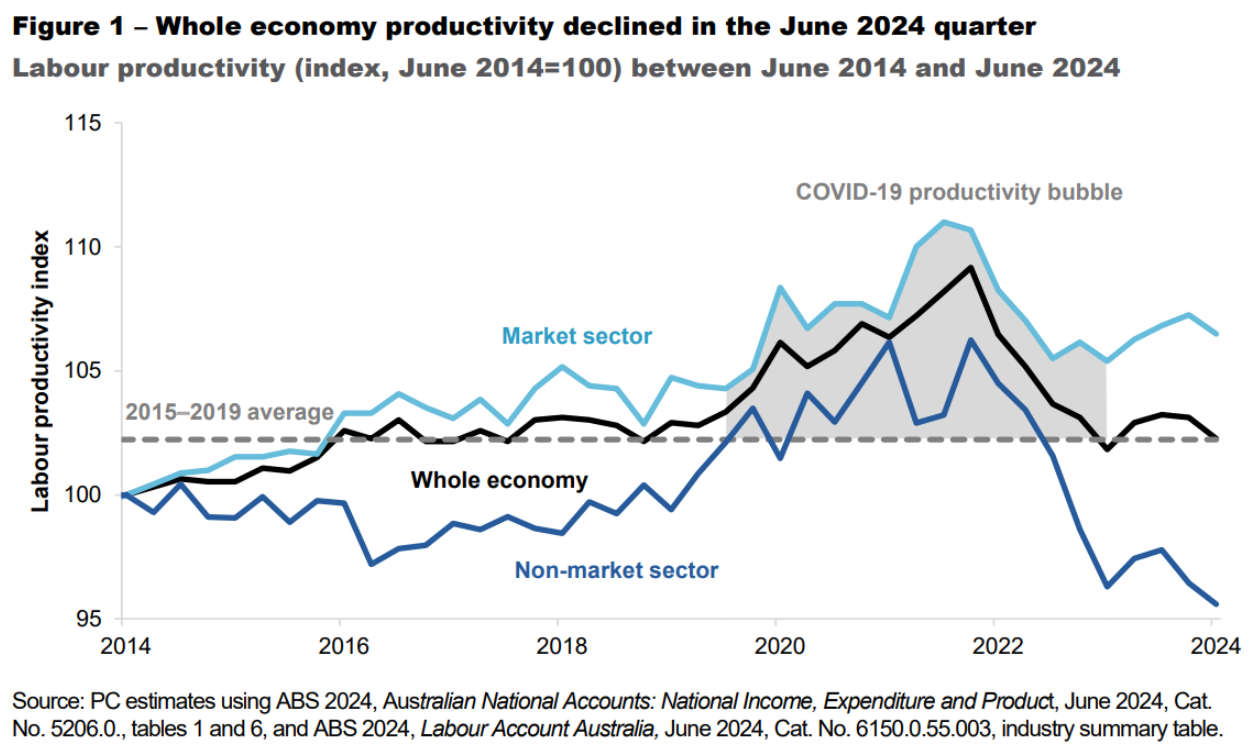

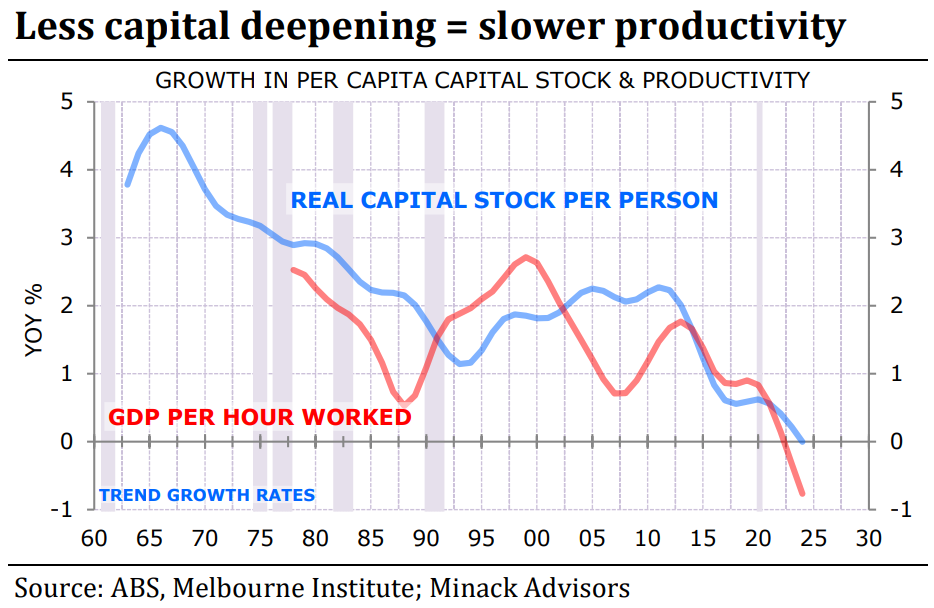

Ultimately, for real incomes to grow in a sustained way, Australia’s productivity growth must accelerate.

This seems unlikely, given that Australia’s economic model is centred around importing large volumes of people to work in lower-productivity service industries, much of which is government-funded.

This economic model has overrun business, infrastructure, and housing investment, delivering decades of capital shallowing and lower productivity.

Australia will be stuck in the low-productivity lane so long as it continues with the same ‘Ponzi’ growth model.