There’s nothing like McKinsey blowing smoke at the AFR.

McKinsey blamed stagnating national productivity and weaker real incomes on two key trends.

First, the non-market economy, such as disability support, aged care and the public service, has had no productivity improvement for 20 years. These government-dominated industries are growing at almost triple the pace of the market economy.

Second, weak business investment in new tools and equipment has been stuck around 1990s recession levels for the past eight years, making workers less productive.

These are not causes; they are symptoms.

If you want to run an immigration-led economy, alternatively called a labour market growth-led economy, this is what you get.

Gerard Minack has explained this almost as many times as MB has.

The Australian economy has been on public sector life support for a year as a policy squeeze caused a recession-like slump in real incomes. Real income growth is probably past the worst, so there may be a tepid cycle recovery. But Australia faces structural headwinds caused by a combination of fast population growth and low investment which has crushed productivity growth. That points to structurally weak income and spending growth.

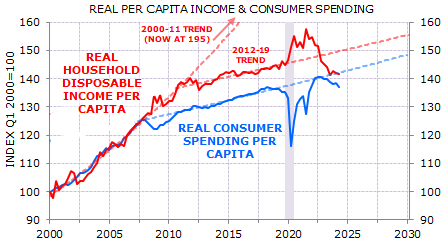

Rate hikes, tax hikes and price hikes led to a recession-like decline in real incomes over the past two years. Part of the decline was payback for the pandemic-era fiscal largesse. However, real incomes are now well below the anaemic trend that’s been in place since 2012 (Exhibit 1).

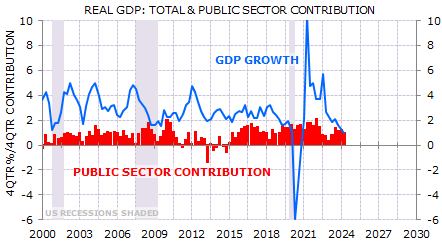

Private sector demand flat-lined over the past year. The economy was on public sector life support: the public sector has accounted for all of the (low) 1% GDP growth seen over the past year (Exhibit 2).

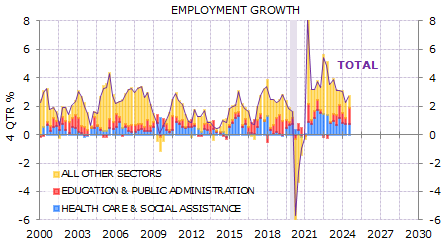

In contrast, labour demand has been exceptionally strong: employment growth remains near 2½%. However, jobs growth has been concentrated in publicly funded sectors while growth in private sector employment has sharply slowed (Exhibit 3).

Real income growth may be past the worst: income tax rates fell from 1 July, there are no more rate hikes in the pipeline – and there’s only a small tail of fixed rate mortgages yet to reset to floating rates – and headline inflation is falling. However, it’s also likely that nominal wage growth will slow, and the RBA has effectively signalled no rate cuts until 2025. Any recovery will likely be modest.

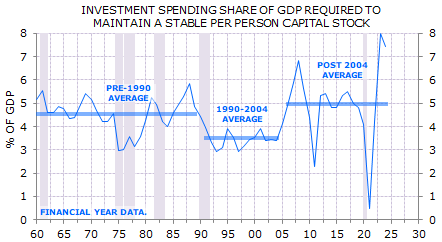

Australia faces serious structural headwinds even if the cycle improves. The first problem is low investment. Net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession (Exhibit 4).

The second problem is that investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth. Population growth naturally requires investment in public infrastructure and housing. This investment doesn’t improve living standards, it’s required to stop living standards from falling. If investment doesn’t match population growth, then schools, roads and hospitals become more crowded, and housing shortfalls increase house prices and rent.

Exhibit 5 shows an estimate of the investment needed due to population growth: the investment share of GDP required to keep a stable per person capital stock.

Over the past two decades, Australia has required an average investment of 5% of GDP to maintain a stable per capita capital stock. Currently, investment levels are approximately at this threshold, as illustrated in Exhibit 4. Excluding the mining sector, investment has been close to this level since 2012.

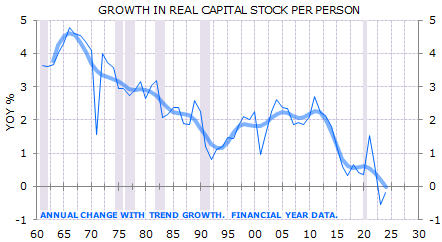

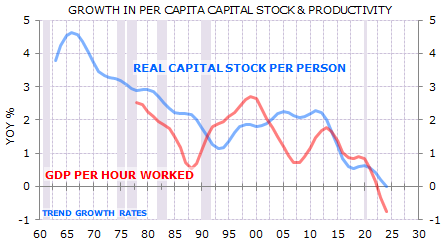

The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock (Exhibit 6).

Increasing capital per person – so-called capital deepening – is crucial to productivity growth. Less deepening means less productivity growth (Exhibit 7). To be fair, the pandemic shutdown and reopening led to large swings (up, then down) in measured productivity. But this is an issue that pre-dates the pandemic. Productivity increased by just 0.1% in FY2019, the year before the pandemic.

Australia’s structural growth problem has been increasingly obvious since the mining boom peaked in 2012: low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth. The renaissance in Australian productivity from the late 1980s to 2000 was undoubtedly driven by major structural reforms. But it also coincided with the slowest population growth of the post-1945 era.

The first thing we should do to fix the problem is stop digging the hole deeper.

Slash immigration so that the population stops growing.

This will lower capital costs as interest rates fall with the currency while construction costs and rents deflate.

Over time, wages will firm up and boost demand.

Both will trigger more business investment as firms look to defend margins.

It would also help a great deal to crush the gas cartel to crater energy costs.

Hilariously, the AFR would be at the forefront of resistance to these reforms.