The AFR’s Ronald Mizen has published an article describing Australia’s broken ‘skilled’ visa system, which is importing many purportedly skilled workers who end up working in menial jobs such as driving Uber.

The article profiles engineer Muhammad Ahsan Siddiqi, who migrated to Australia from Karachi in Pakistan in 2010 to drive Uber and work security.

“More than 620,000 permanent migrants work below their skill levels and qualifications, according to Deloitte Access Economics”, writes Mizen.

“And of these, about 60 per cent, or 372,000, arrived in the skilled migration system”.

It is a story that is as old as the hills.

Last year, The AFR’s education editor Julie Hare wrote that an “army” of migrant engineers is driving Ubers.

“Only 50% of qualified engineers born overseas currently working in Australia are working as engineers – a reality that is impacting the nation’s ability to address the national infrastructure deficit and generate economic growth”, Engineers Australia chief executive Romilly Madew told Hare.

“An army of well over 100,000 qualified, skilled engineers are currently in Australia, driving Ubers or doing some other kind of work that is not related to engineering. This is an emerging national disaster”, she said.

The malfeasance of Australia’s ‘skilled’ migration system cannot be overstated. We are depriving poor nations of their talent while exacerbating skills and housing shortages at home. It is a lose-lose situation.

The macroeconomic data backs this view.

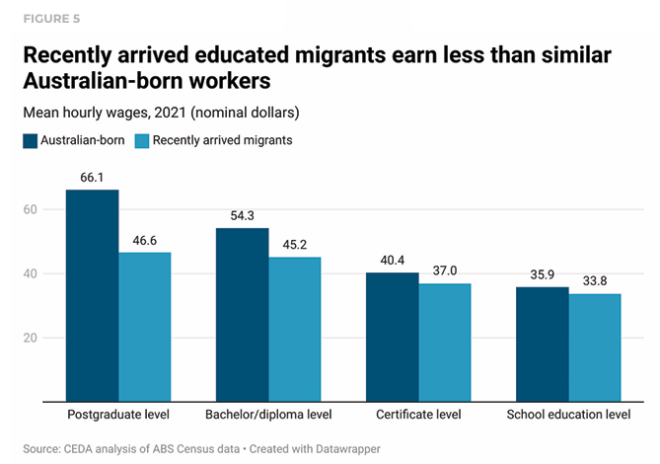

Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) research showed that half of skilled migrants work in occupations below their qualifications and earn significantly less than Australians with the same skills.

Even with identical qualifications, migrants living in Australia for 2-6 years earn at least 10% less than Australian-born citizens (see chart below).

CEDA stated that their incomes could take up to 15 years to catch up to locals.

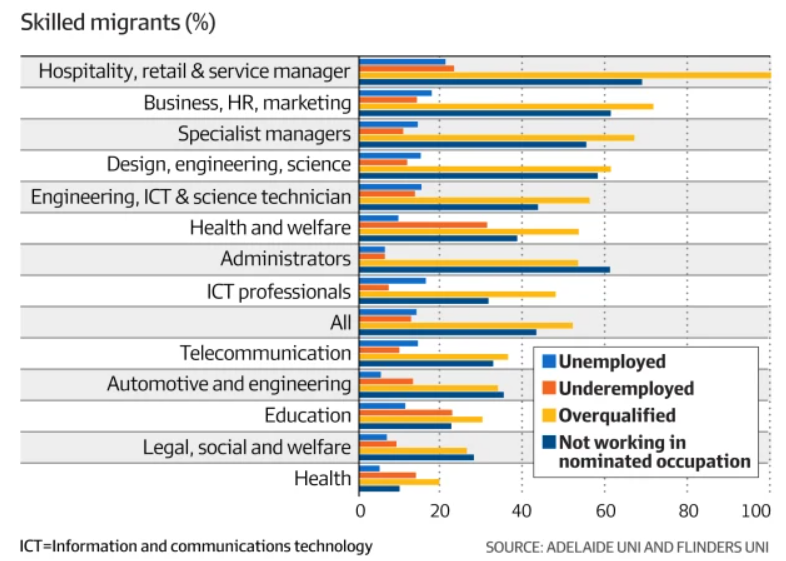

Research from Adelaide University’s George Tan showed that 43% of skilled migrants who used the state-government-sponsored visa system were not engaged in their nominated occupation.

The vast majority of skilled migrants worked in retail, hospitality, and service managers and were overqualified for their positions.

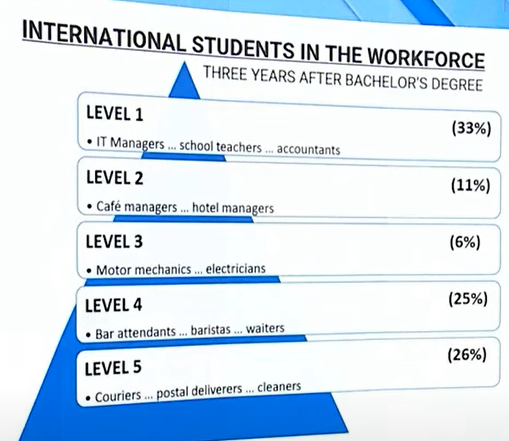

The 2023 Migration Review from the federal government revealed that 51% of overseas-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review (2023)

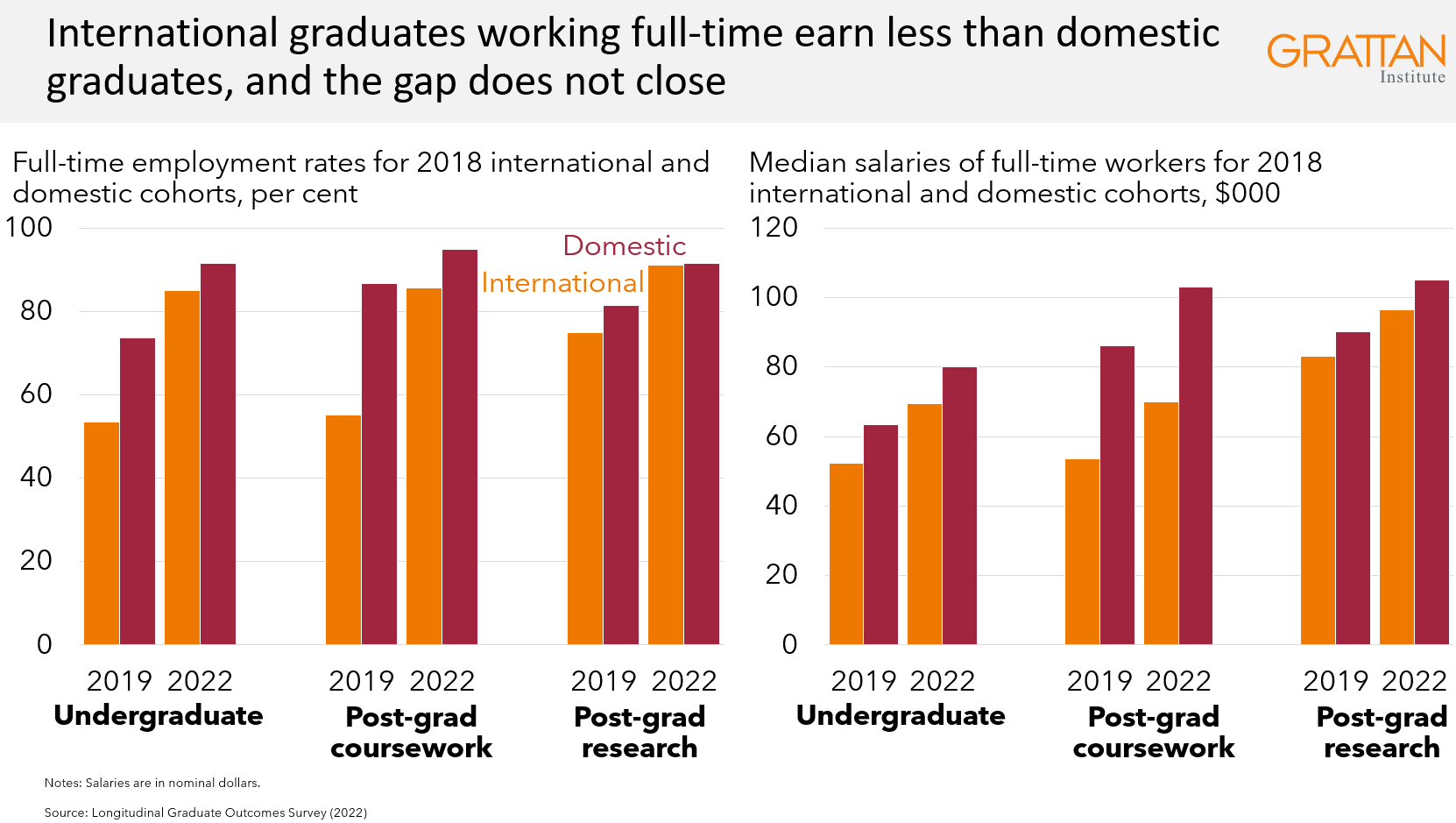

Finally, the Graduate Outcome Survey revealed that student graduates earn far less than local-born graduates and have worse labour market outcomes:

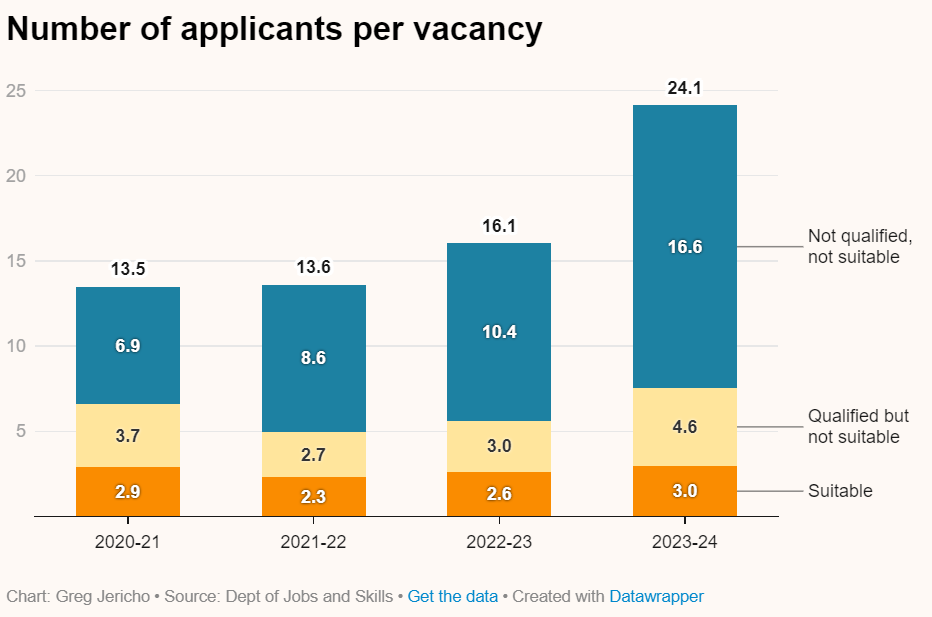

Greg Jericho from The Guardian released research in October showing that “we still have very high skills shortages” despite record levels of migration.

Jericho also showed that these shortages were not because we lacked applicants, which have swelled in number. “There are a lot more people applying for each job”.

Rather, it was because there was a lack of “qualified and suitable candidates applying for jobs”:

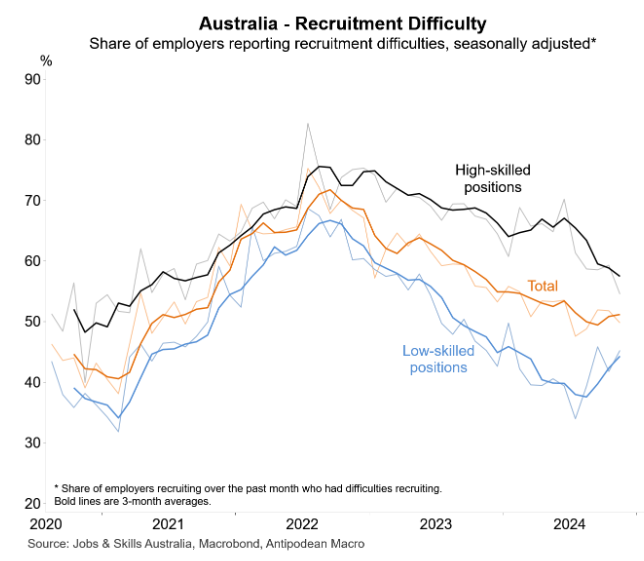

The below chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro likewise shows that despite record immigration, Australia is suffering from a chronic shortage of highly-skilled workers but is well supplied with lower-skilled workers:

All Australians should question why we have such a massive immigration program given the majority of the migrants we import work in unskilled jobs, often unrelated to their area of qualification.

Surely the optimum strategy would be to make all skilled visas employer-sponsored, allowing qualified migrants to start working in their field of competence as soon as they arrive?

Australia should also raise the minimum pay for all skilled visas above the median full-time wage (now around $90,000).

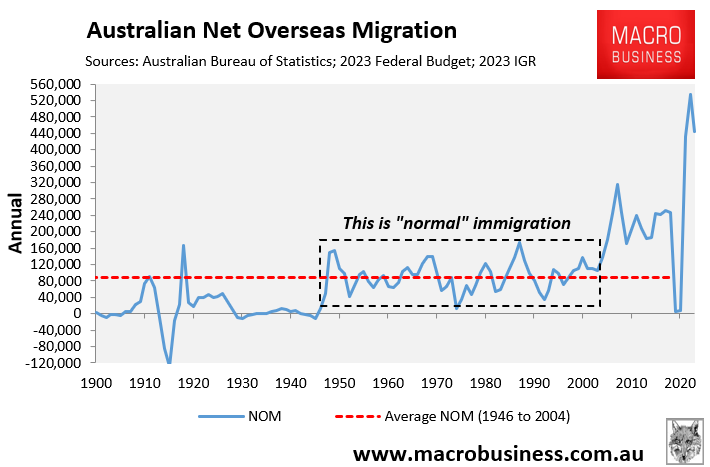

The fact that Australia’s population has grown by 8.5 million people (45%) this century alone, while skills shortages are worse than ever, demonstrates the inherent flaws in Australia’s purportedly ‘skilled’ migration system.

The current system creates skills shortages by supplying the economy with the incorrect types of workers and worsening housing and infrastructure shortages.

Australia requires a much smaller immigration system focusing on the skills we need.