Australia’s homebuilding industry ended 2024 in a slump.

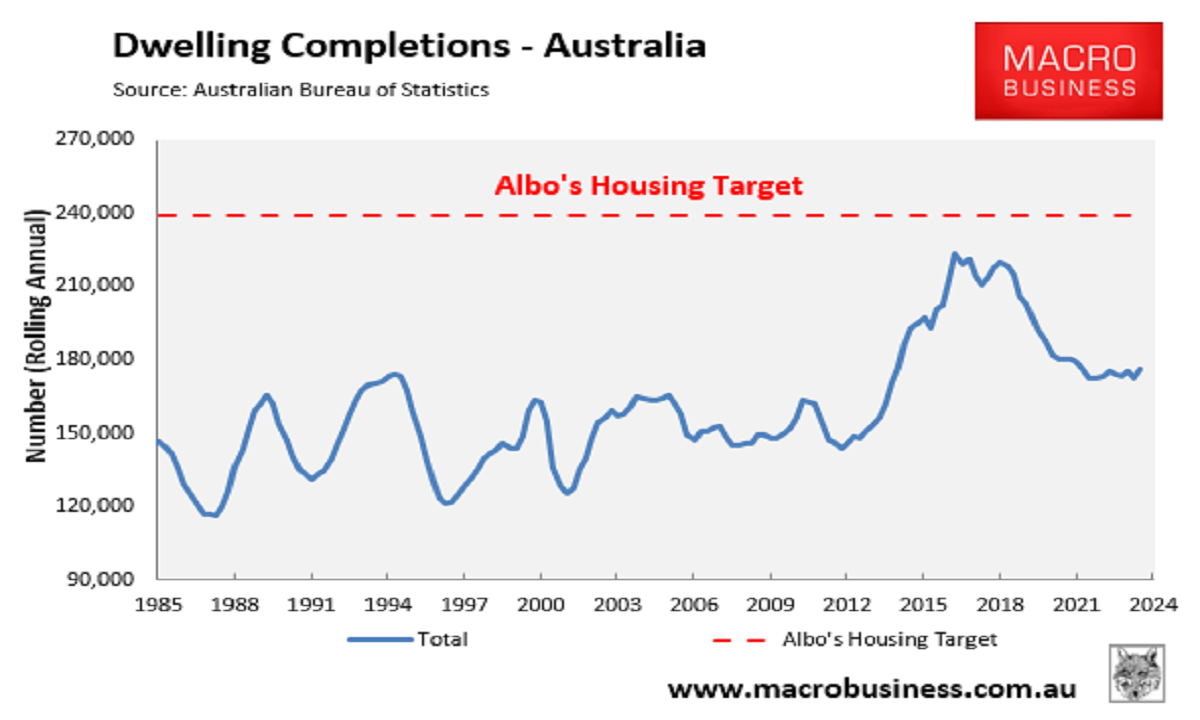

The latest data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that only 176,100 dwellings were completed in the year to Q2 2024, around 63,900 (27%) below the Albanese government’s target of building 240,000 homes annually for five years.

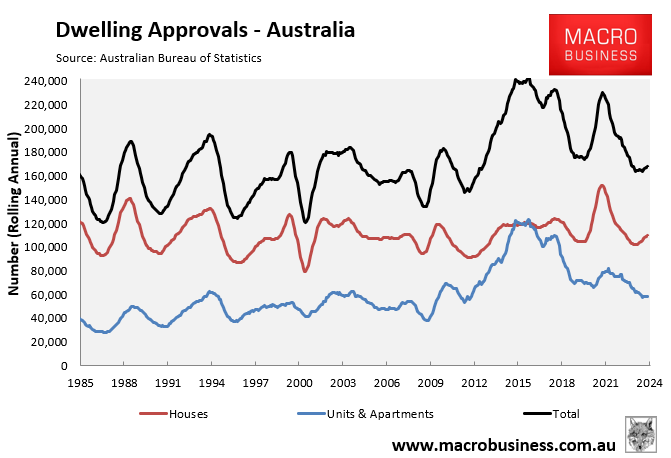

The forward-looking indicator of dwelling approvals is even weaker, with only 168,200 homes approved for construction in the year to October 2024.

PropTrack has released its Property Market Outlook, which forecasts that Australian housing will remain weak in 2025:

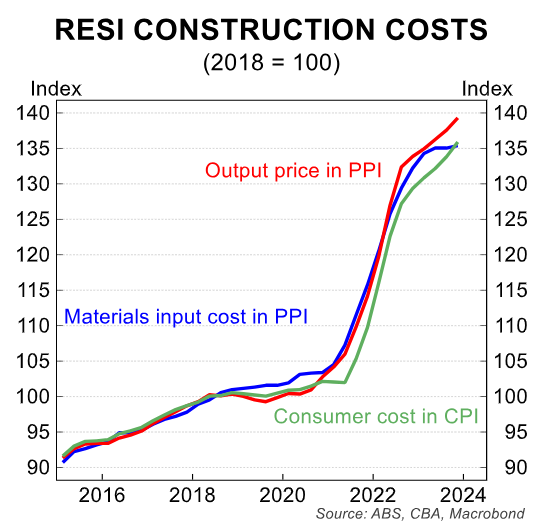

The surge in construction costs is expected to keep new construction activity constrained in 2025. Persistent shortages of labour and higher interest rates are likely to make reaching presale targets more difficult and finance for new construction more expensive to obtain.

The significant cost of constructing new properties means there is a price premium for new properties compared to existing. In turn, buyers are preferencing existing properties, which is resulting in less new housing being built and the overall shortage of housing stock being exacerbated.

What is being built is smaller, such as new houses on smaller lot sizes on the outskirts of our cities, or larger and more expensive units targeting higher wealth owner occupiers and/or downsizers.

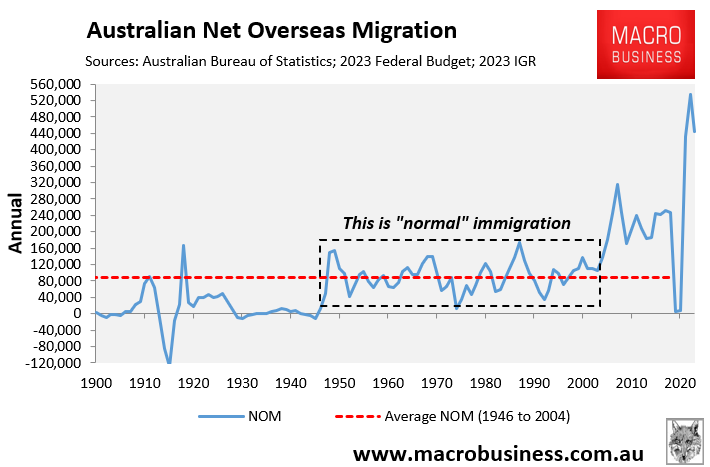

A further challenge magnified by the low volume of new housing construction is that the population continues to expand rapidly, largely due to the rapid rate of net overseas migration…We expect elevated levels of migration to continue.

The homebuilding industry faces a raft of constraints that prevent a strong rebound in construction.

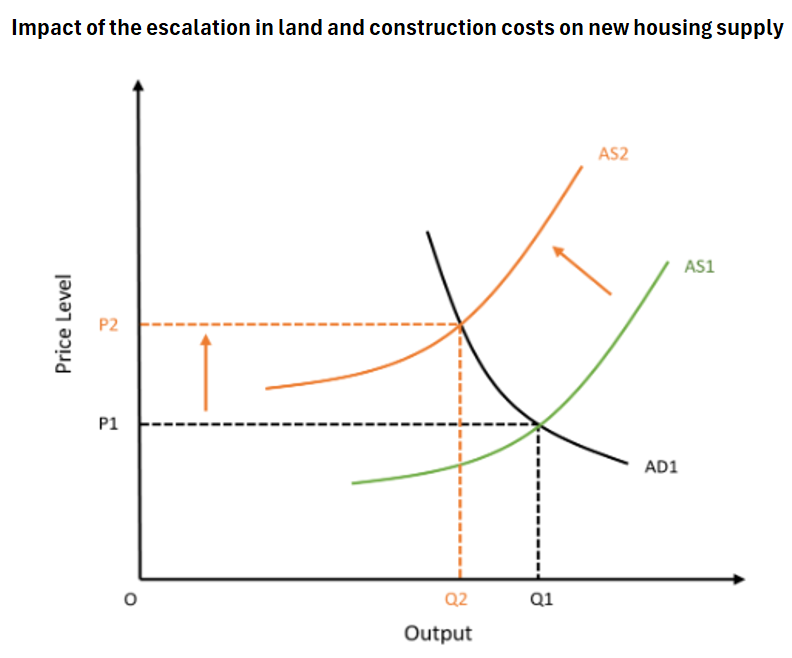

First and foremost, construction costs are now around 40% higher than they were pre-pandemic.

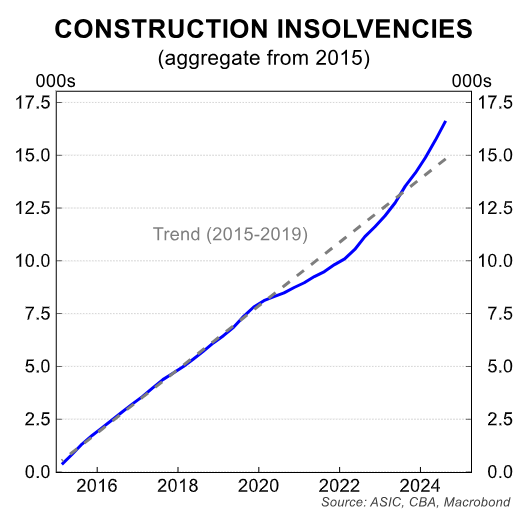

Second, a large number of construction firms have collapsed, reducing capacity in the industry.

Finally, Australian interest rates are likely to remain structurally higher than they were pre-pandemic.

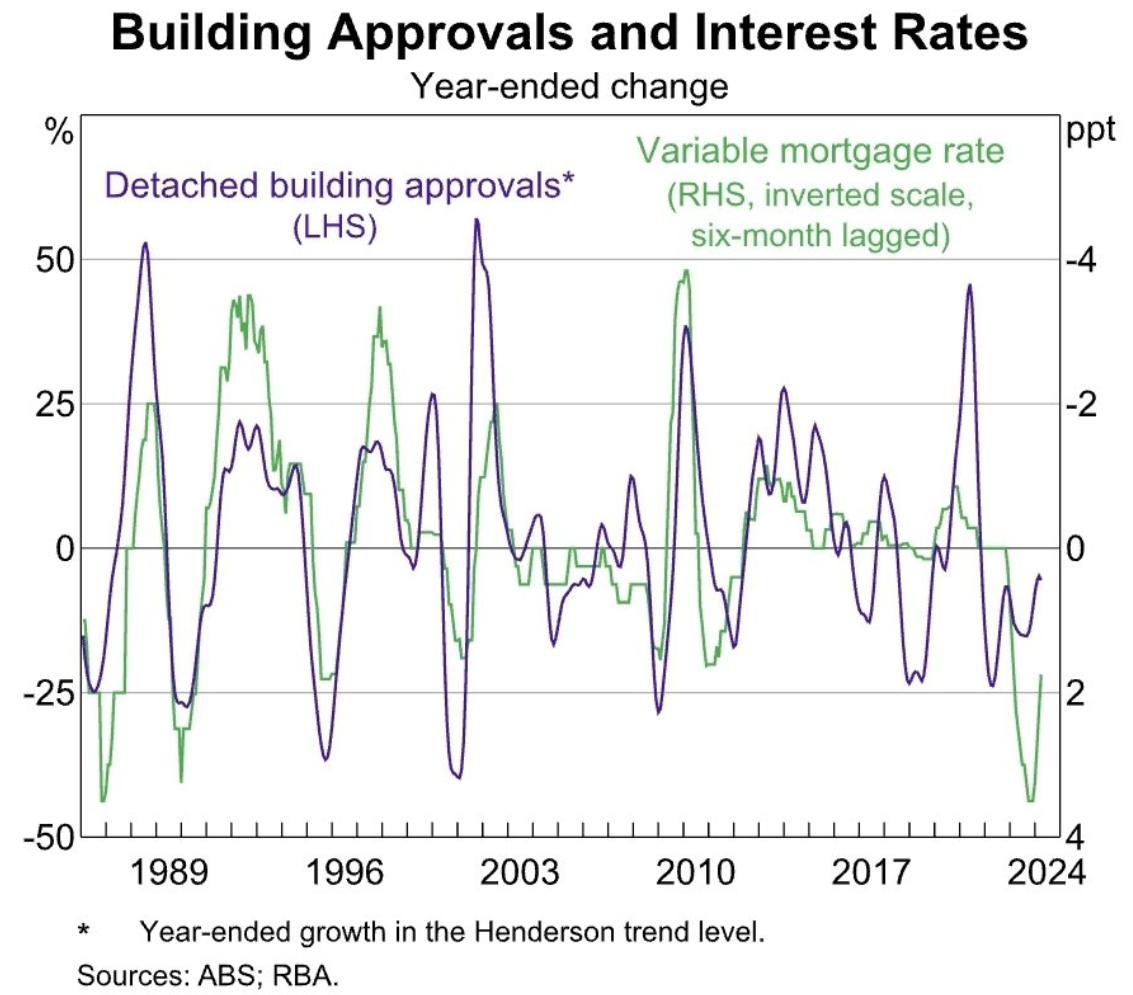

The importance of higher interest rates cannot be underestimated. As illustrated in the following RBA chart, there has historically been a strong correlation between mortgage rates and dwelling approvals.

In other words, there are multiple factors working against a significant rebound in housing construction. These factors have effectively shifted the supply curve for housing to the left, reducing capacity and increasing cost.

The logical policy response would be to reduce demand commensurably by cutting net overseas migration to a level compatible with the supply side.

Sadly, Australia’s policymakers refuse to take this option and instead try to present the problem as a supply issue, not an excessive demand issue.