By Stephen Saunders

The way things are going, this new report on student-migration policy scarcely needs those last four words in its title.

In November 2024, the Coalition voted down Albanese Labor’s “cap” or “quotas” on student visas and their misleading misinformation bill.

This Australian Population Research Institute (TAPRI) report retraces the migration-policy year, illustrating a typical Labor progression: a double somersault with pike, jarring ministerial and portfolio discordances, studied misrepresentations, with scant regard for citizen voters.

Another recent TAPRI report rated housing affordability as “beyond the reach” of most aspirants. They attribute this to investor demand—both upgraders and new-home seekers—, especially from a “huge bank-up” of recently, arrived migrants.

This follow-up report considered the immediate housing “hotspot”—a lack of affordable rentals. Though Sydney has recently (September 2024) reported marginal gains in rental affordability, it is still “urgent” to relieve the overseas student deluge.

In late 2023, TAPRI asserts that Labor had reached a “similar” judgment regarding overseas students and rental affordability. But vested interest whingeing induced them to “change course”.

The government had initially promised to restrict student visas via a “genuine student” test, implying that fake students were previously welcome.

But once the moaning began, Labor regrouped. Under Plan B, the Education Department would impose “quotas” for (post-secondary) education providers. These “quotas” would add up to 270,000 students for 2025.

That’s the academic or calendar, not the budget or financial year. It includes university and vocational sector students, but not higher-degree students, or English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS). It also doesn’t seem to include accompanying family. Tricky, tricky.

The media were inclined to present this intricate ploy as tough stuff.

Quotas for 2025 have already been allocated. TAPRI estimates that the actual number of student visas issued will be “close” to the towering 2023 total. At best, they will be “fractionally” down.

“Students” are half of immigration

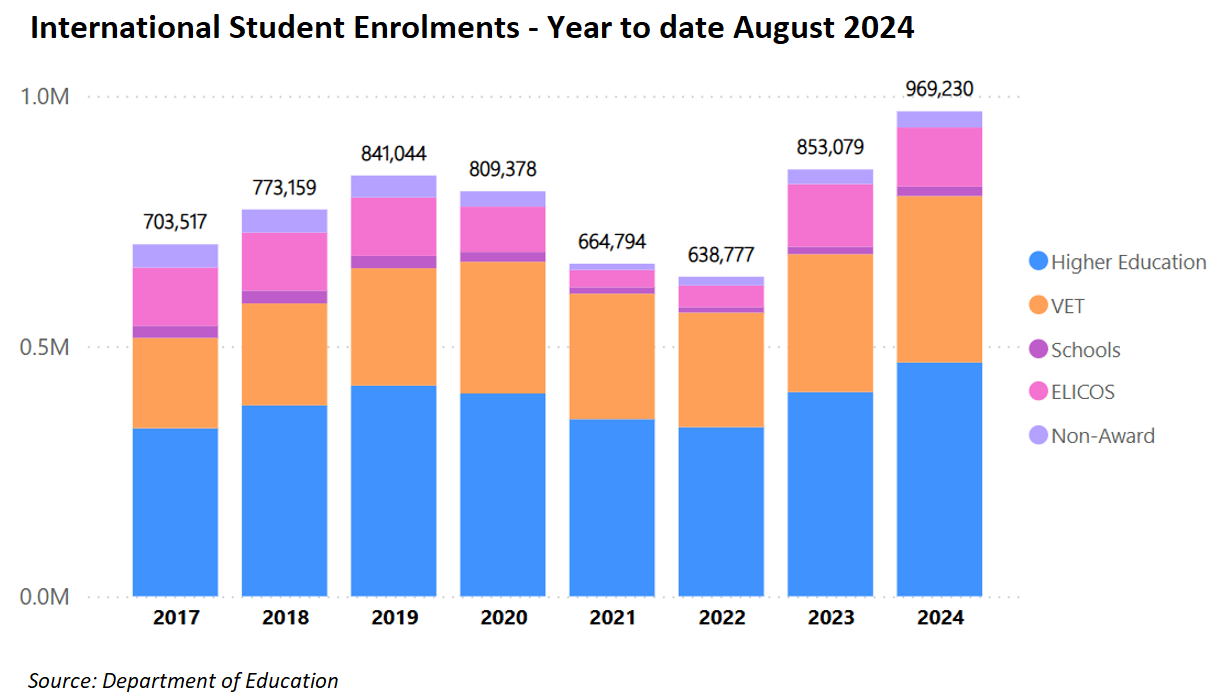

The report calculates that “students” (vocational, university, other) made up more than half of the overwhelming 518,000 net migration in 2022–23. The government’s own Population Statement says much the same.

Many students come to Australia as a “way to enter the labour market”. That is, a way to stay for the duration. To that end, they “hop” between visas, of which the Department of Home Affairs happens to offer a helpful selection.

In theory, the “genuine student” test promised to arrest this student influx and the large numbers staying on for “years afterwards.”

“Genuine student” policies

These measures, TAPRI assesses, were “not token” and “hit hard”.

Under Home Affairs Ministerial Direction 107, Vocational and ELICOS felt the heat: bigger application fees, barriers to visa-hopping, plus a higher English-language hurdle.

In the five months to May 2024, primary (not including partners) visas for vocational and ELICOS halved, relative to the same period in 2023. Primary visas for higher education also fell by less than a quarter, down to about 200,000.

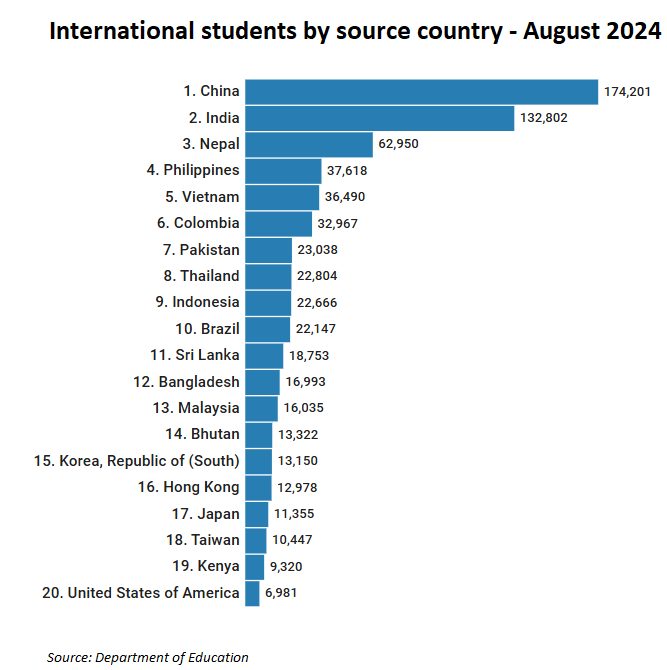

Direction 107 had presumed correctly. Indian students at second-tier universities are much keener to stay on than Chinese students at elite universities.

The backlash and the retreat

The universities (and allies) complained that Direction 107 was stifling enrolments for 2024. This would cripple their corporate finances and employment numbers, also hurting immigration-loving state economies. Oh dear.

A September 2024 Financial Review article, quoting Universities Australia, asserted a “wipeout” of $4 billion in university revenues. The migration-addled and debt-ridden Victorian Government directly repudiated any federal reductions in student visas.

Or, as I would interpret it, Victoria’s Indian loyalties overruled their Australian loyalties.

During this back-and-forth, there was an assumption that “quota legislation” would eventually replace Direction 107. It would reduce student intake (not true) and mitigate the housing crisis (also false).

The Education Department was on a different page from Home Affairs. As early as May 2024, their minister was talking up “sustainable” (is there any other kind?) growth in student numbers.

TAPRI infers that the new quota regime and its allocations will “rescue” rather than reduce the 2025 numbers, especially at universities that enrol students who aren’t up to the “genuineness” test.

However, following the legislative defeat in November, the implementation of these Education Department quotas may need to remain within the purview of Home Affairs. The “genuineness” test looks tattered.

Students and housing demand

In the ABC and university narrative, incoming students exert a magically light touch on our accommodation market. Twenty people crammed into a two-bedroom Sydney apartment. But in ABC and university terms, it is still a supply-side problem. It might be too racist to allude to the demand side.

Ironically, the Education Department’s own September 2024 Factsheet knocked the paint off this preferred narrative. As TAPRI notes, the Department estimated that half (135,000) of the 270,000 overseas students slated for 2025 would enter our rental market.

But remember, that initial 270,000 doesn’t include visas for accompanying family or ELICOS sector visas. It also doesn’t take departures into account.

What really matters is the all-up 2025 “net expansion” via all students—net migration. That’s how many warm bodies might need accommodation. Not the 135,000.

Conservatively, TAPRI calculates that expansion as 200,000, which is below the current trend.

Extrapolating from Census and migration data, they estimate that even this 200,000 would lead to an “additional rental demand” of about 40,000 dwellings in Sydney plus Melbourne. However, these cities’ current supplies of (student-friendly) medium- and high-density dwellings are only about half of that.

Reforming the universities – maybe

“Whoever wins the 2025 Election will have to diminish the demand side for housing if there is to be immediate progress in solving the housing crisis,” TAPRI concludes. “The most feasible option is a reduction in the overseas student influx.”

Clearly, Labor’s student “reduction” won’t cut it. The Coalition claims they would make deeper cuts—without really saying how. As for the Greens, the mere mention of the m-word triggers hysterical accusations of “migrant bashing” on a “race to the bottom”.

TAPRI argues that genuine reductions in student numbers could enhance the electoral appeal. More so if universities were also required to put local students first. Now there’s an idea.

TAPRI also suggested that Australia could cut its net migration aggregate by requiring more students to go home. Instead of the blight, we have a large “underclass” of “permanent temporary” students.

Or not – reforming the universities

This report is valuable as a stepped record of migration-policy pivots. It reverts to a familiar pattern: a surge in immigration levels and rapid population growth. This pattern is the bane of voters but beloved of governments, in service of influential “stakeholders.”

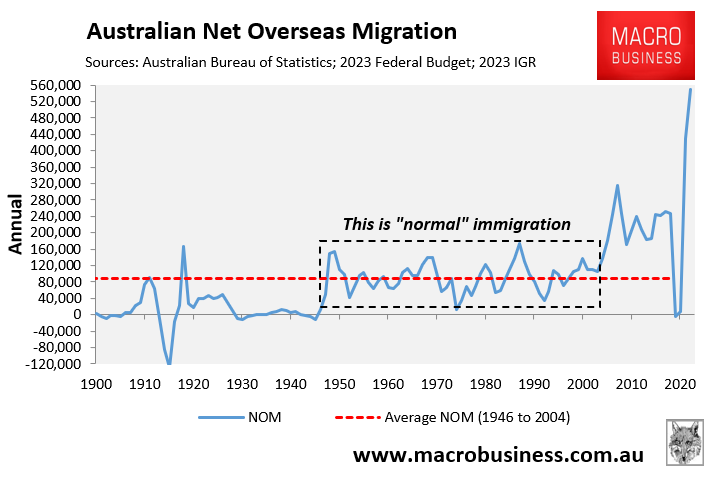

Net migration exceeded 500,000 in 2022-23 and 2023-24. I expect it to exceed 400,000 for 2024–25.

Even compared to the pre-COVID Big Australia years, these Labor numbers are off the charts. They’ve pushed the population growth rate twice as high as the rate of economic growth.

But “stakeholders” are unlikely to face drastic reductions in net migration after Election 2025. They will be able to keep on with what they enjoy most. Sensible conversations among their entitled selves towards a sometime-never population plan.

The current chief of the Prime Minister’s Department helmed the University of Melbourne for a record 14 years. Where we are at now, the corporate rot at our universities would be devilishly difficult to undo.

Yet it’s only 20–25 years ago that the so-called export education (and Big Australia) really took flight with a leg up from internationalist (globalist, we’d call them nowadays) mandarins at the Education Department.

No other major OECD nation exhibits such a pronounced reliance on the student-migration boondoggle. TAPRI describes this as a rejection of any “alternative means” for financing its universities.

Our captured media, academia, and mandarins love the Universities Australia upside of export education. And they are more than willing to overlook the unedifying Daily Mail downside.