If you want a prime example of why I have little regard for academics, consider the below housing non-solutions from the University of Queensland on “How can we solve the housing crisis?”.

Dr Dorina Pojani, Associate Professor of urban planning School of Architecture, Design and Planning Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Information Technology, says that Australia needs rent control to solve the crisis.

“Rent control (or stabilisation) would provide some relief to sitting tenants, which comprise nearly one-third of Australian households, without burdening the public largesse. All that is needed is political will”, she says.

Professor Tim Reddel and Dr Laurel Johnson from the Institute for Social Science Research Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, claim that Australia needs more social and affordable housing to solve the crisis:

We suggest 5 action areas:

- Quality and accessible social housing that is co-designed with tenants and mixed throughout local communities, rather than located at their edges.

- Social housing seen as part of a housing ecosystem by the Queensland Government working with the Federal Government, community and private-housing sectors to respond to key challenges – including climate change, the trend to smaller household sizes, growing social inequity and rising homelessness.

- A more integrated person-centred service system aligned with improved social housing provision, particularly for people with complex needs.

- Better integration of the land use planning system with housing planning and delivery.

- Empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled housing organisations to enable self-determination through community leadership and shared decision-making with governments.

Stephanie Wyeth, MPIA Fellow, Professional Planner in Residence and Senior Lecturer School of Architecture, Design and Planning Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Information Technology, claims that the solution rests with better urban planning and design:

For those seeking to tackle the crisis this election there are seven key points to consider:

- Play the long game. The housing crisis will require sustained action over the medium to long term to address shortfalls and keep up with population growth and demographic change. There will be a national shortfall of 106,300 dwellings in the 5 years to 2027.

- Don’t forget the regions. Plans for affordable housing need to be uniformly applied across the state.

- It’s hot and getting hotter. We need data-informed scenario planning to deal with the impacts of climate change. Severe weather events and sea level rises will impact where and how we build as well as increase insurance premiums beyond just the far north.

- Adopt inclusionary planning. Mandatory inclusionary zoning is a tried and tested tool for delivering affordable housing in all levels of government in Europe and the US.

- Rethink how we design, plan and regulate. Partnering with industry to design homes for smaller households, use less energy and materials, and reflect modern life.

- Maintain the urban footprint. Don’t make the mistake of extending the urban footprint – as some have called the ‘carpet of suburbia’ – at the expense of protecting the state’s green spaces, waterways, good-quality agricultural land and natural resources.

- Listen to communities. Identify pain points with local planning and development projects and advocate for designs which deliver resilient, affordable and well-designed housing for all cultures and demographics.

Professor Cameron Parsell, ARC Mid-Career Industry Fellow School of Social Science Faculty of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, wants Australia “to commit to ending homelessness”:

A formal commitment to end homelessness, backed up with a detailed strategy, is the first step.

Second, and of crucial significance, ending homelessness in Queensland (and elsewhere in Australia) requires demonstrably increasing the supply of social and affordable housing. Homelessness is a problem of too few affordable housing dwellings…

Third, the government plan to increase supply is excellent, but it will not happen without wide and sustained public support. Ending homelessness requires not only supporting the notion of everyone needs a home, but also supporting and, ideally, advocating for more affordable housing in our neighbourhoods and communities.

Fourth, the commitment to end homelessness, the increased supply of social and affordable housing at the population level, and the active support for more of this housing where will live will be greatly enhanced when we as individual citizens actively see ending homelessness as a unifying endeavour.

Have you ever seen such a word salad of virtue signalling and motherhood statements?

As usual, there is zero discussion of the primary driver of Australia’s housing shortage, rental inflation, and homelessness: excessive population growth via net overseas migration.

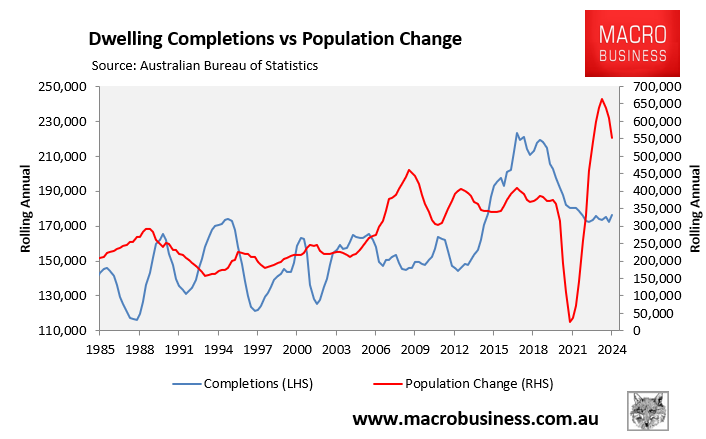

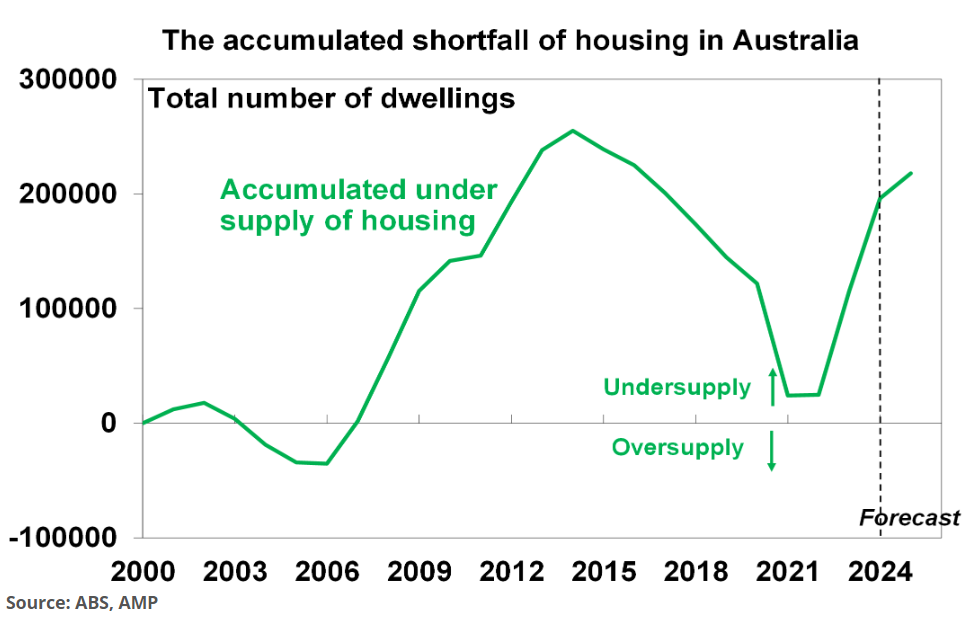

This extreme population growth since 2005 has driven the shortage of housing.

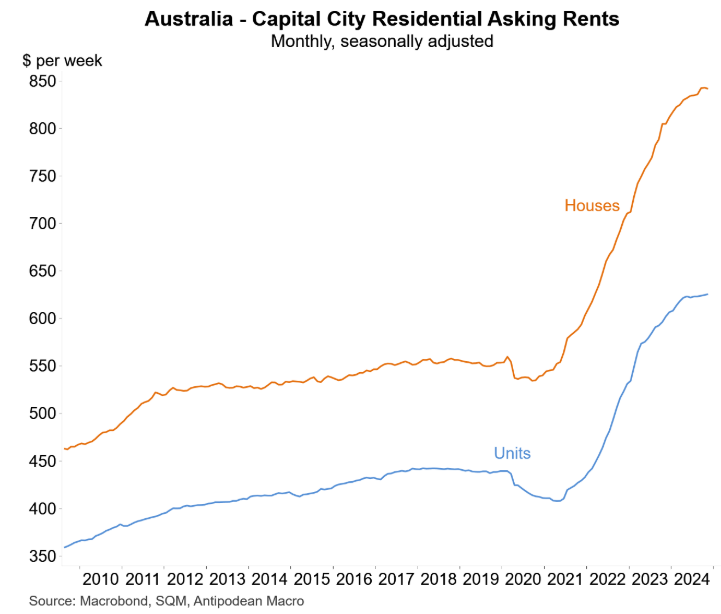

It has also driven the recent huge rise in rents and the corresponding increase in homelessness.

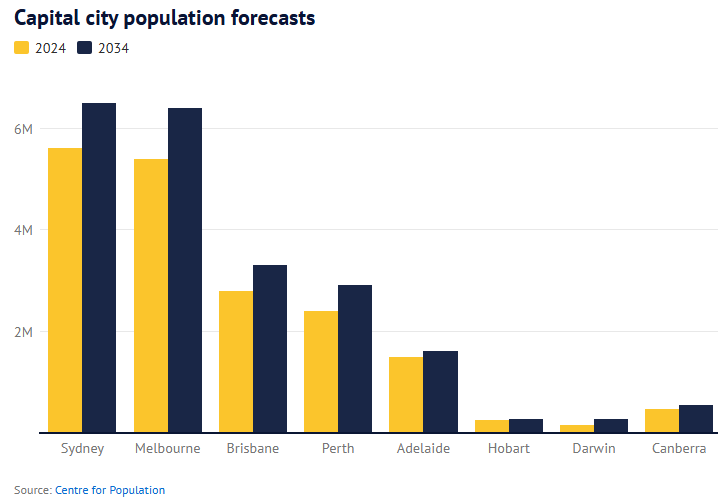

The Centre for Population’s 2024 Population Statement, released last month, forecast that ongoing high immigration will add 4.1 million residents to Australia over the next decade—most of whom will live in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Under these population projections, Australia would add nearly a Canberra-worth of population every year for 10 consecutive years.

Melbourne’s population is projected to balloon by one million people over the coming decade, Sydney’s by 900,000 people, whereas Brisbane’s and Perth’s populations are projected to swell by 500,000 apiece.

There is no getting around the fact that such rapid population expansion, driven almost entirely by net overseas migration, will worsen housing and infrastructure shortages.

Australia simply cannot build enough social or other housing to keep pace with such a population deluge.

The cheapest, easiest, and fastest solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to reduce net overseas migration to a level that is below the capacity to supply housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing crisis will worsen.

Why won’t Australia’s academics acknowledge these basic facts?