A KPMG survey of 320 C-suite executives and board directors about their major challenges over the short and medium term cited high house prices and skyrocketing rents as the top areas of concern affecting the economy.

“Forty-eight per cent of business leaders named “meeting the challenges of housing availability and affordability” as the top social issue affecting their operating environment – more than any other topic, according to KPMG’s seventh annual Keeping Us Up At Night report”, reported The AFR’s Michael Read.

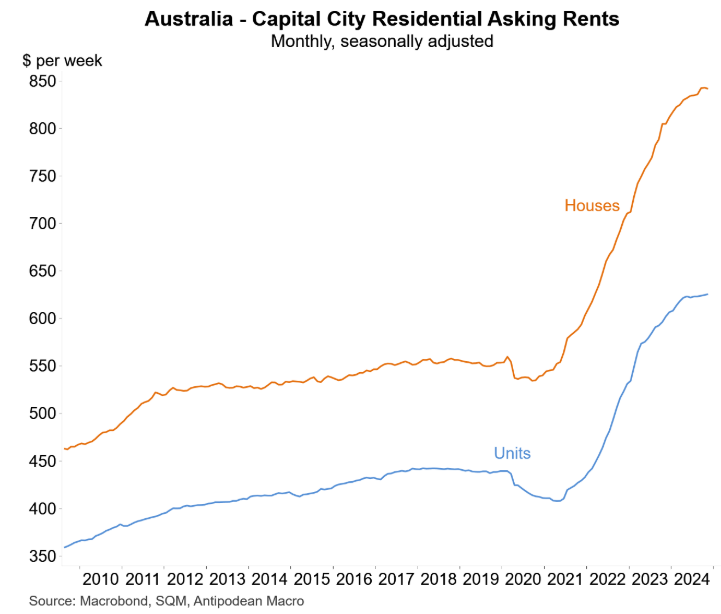

“The median capital city dwelling now costs just shy of $900,000… Rental affordability has also worsened over the past couple of years due to a chronic supply shortage”.

“We just simply haven’t built enough. So what that’s then created is this recognition within businesses that their workforce is finding housing affordability even more of a problem, which then starts to limit individuals choosing places to work. It makes it harder for people to work out where to live and how to travel to work”, KPMG chief economist Brendan Rynne said.

“There is a direct effect on housing policy and business performance, and what’s happened in the last couple of years is that it’s all crystallised”, he said.

Rynne added that the influx of migrants after the pandemic exposed the nation’s housing problem.

Hilariously, a separate CEO survey undertaken by the Australian Financial Review called for more ‘skilled’ migration to alleviate skills shortages.

“We can more actively manage the migrant intake to target the skills we need,” Mr Miller told this year’s Chanticleer survey”, Westpac chief executive Anthony Miller said.

“To meet the government’s housing targets and infrastructure pipeline, we need to increase skilled migration while also investing in training for young people”, Lendlease chief executive Tony Lombardo said.

“Skilled and unskilled immigration must increase”, Stuart Tonkin, who runs $18 billion gold producer Northern Star Resources, said.

No matter what the circumstances, the business lobby also demands more immigration. It has been going on for decades.

For example, a Senate Inquiry from 2002, put forward by the Howard Government on behalf of the business lobby, complained of ‘serious skill shortages and skill gaps’ in Australia and warned that unless we did something about it – i.e. import a lot of workers – Australia’s economy would not develop and would simply end up going backwards.

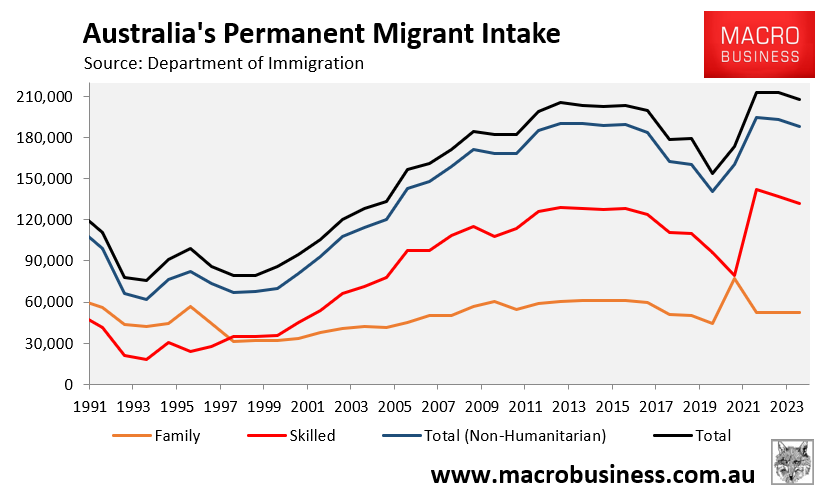

Successive federal governments lifted Australia’s permanent and temporary migrant intakes to record levels in the name of skills shortages.

In turn, Australia’s net overseas migration more than doubled after 2004, with most of it purportedly ‘skilled’.

Despite the record migration, which has driven an 8.5 million population increase this century, Australia’s skills shortages remain. And the business lobby continues to demand more immigration.

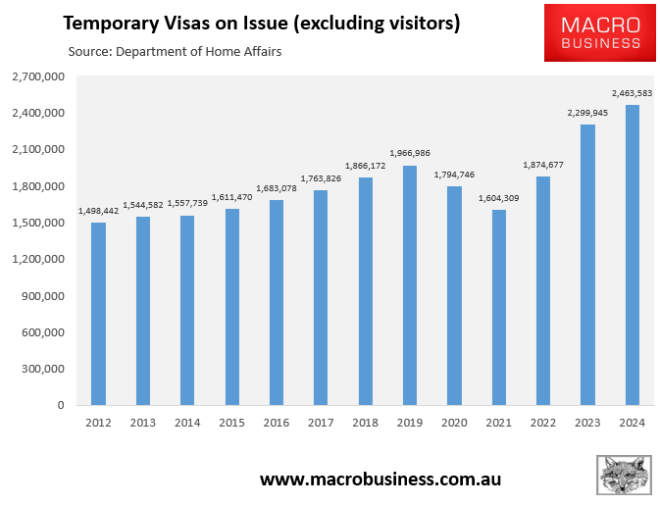

The reality is that most of Australia’s immigration is low-skilled.

Not only has Australia received record volumes of temporary foreign students and working holiday makers, who work in low-skilled jobs, but most migrants and their spouses imported under the skilled stream also work in lower-skilled jobs.

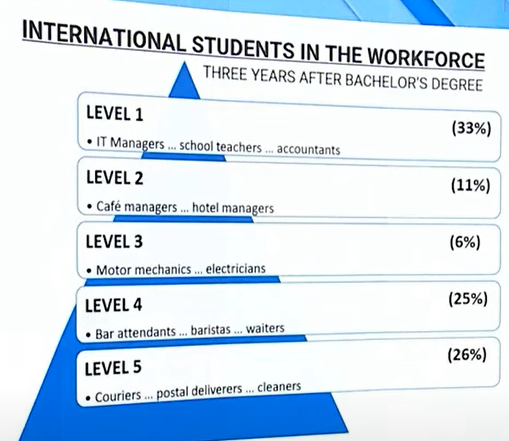

For example, the Migration Review showed that 51% of international university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were working in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review (2023)

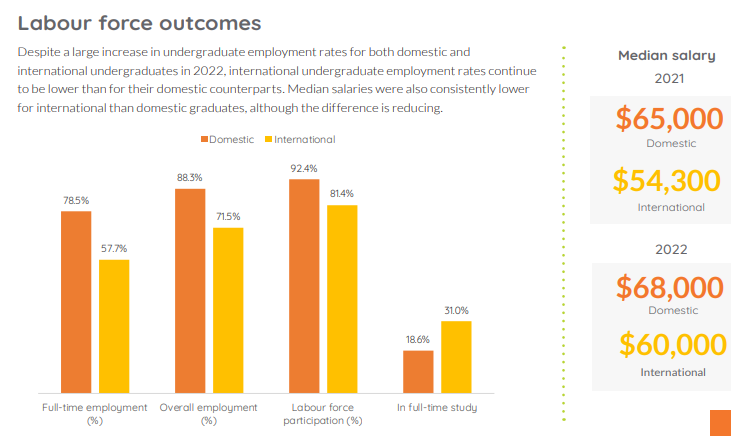

International student graduates earn significantly less than local-born graduates and have worse labour market outcomes:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey

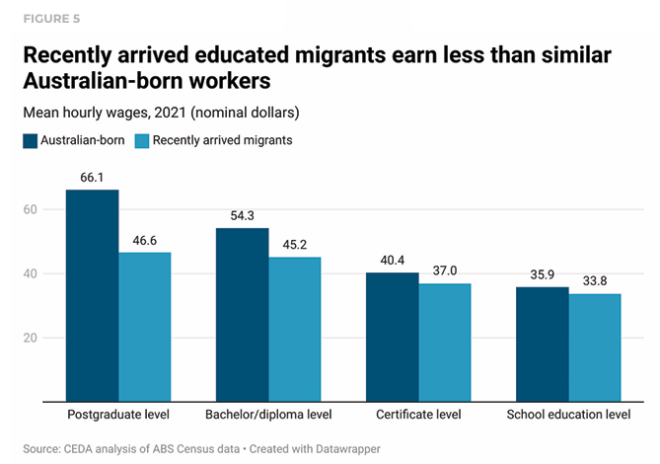

‘Skilled’ migrants get paid over 10% less than local workers:

For example, 60% of Australian engineers are foreign born and nearly half of them work in low-skilled jobs unrelated to engineering, such as driving Uber.

Cover of Engineering Magazine, “Create” in November 2021.

If this is what the business lobby means by “skilled migration”, then the nation is in deep trouble.

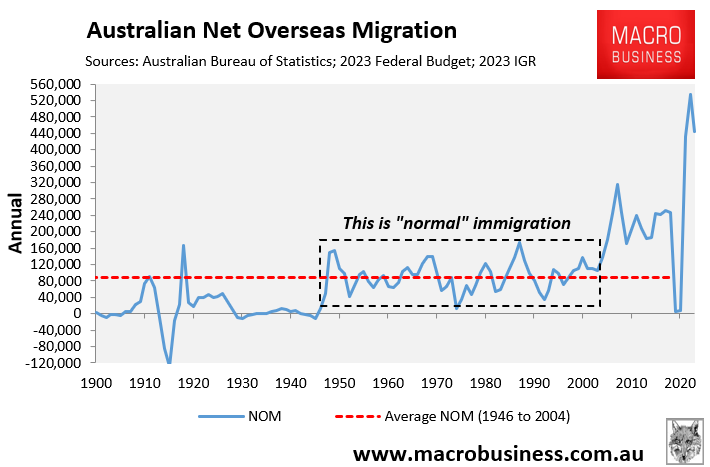

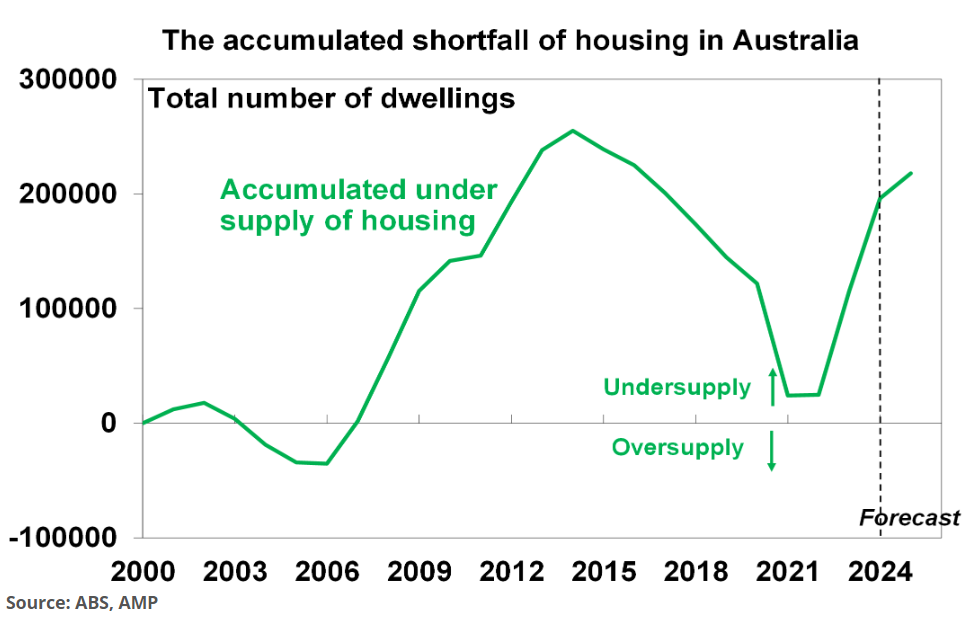

Meanwhile, persistently high immigration is behind Australia’s housing shortage, rental inflation, and rise in homelessness.

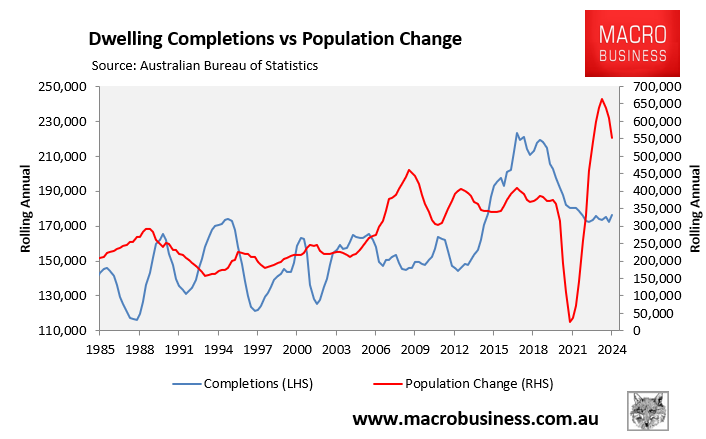

This extreme population growth since the mid-2000s has driven the shortage of housing.

It has also driven the recent huge rise in rents and the corresponding increase in homelessness.

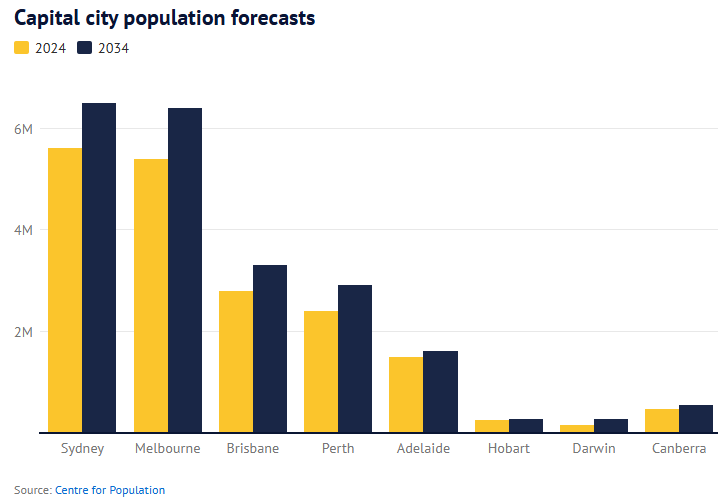

The Centre for Population’s 2024 Population Statement, released last month, forecast that ongoing high immigration will add 4.1 million residents to Australia over the next decade—most of whom will live in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Under these population projections, Australia would add nearly a Canberra-worth of population every year for 10 consecutive years.

Melbourne’s population is projected to balloon by one million people over the coming decade, Sydney’s by 900,000 people, whereas Brisbane’s and Perth’s populations are projected to swell by 500,000 apiece.

There is no getting around the fact that such rapid population expansion, driven almost entirely by net overseas migration, will worsen housing and infrastructure shortages.

Australia simply cannot build enough housing or infrastructure to keep pace with such a population deluge. The past 20 years is all the empirical evidence one needs.

The cheapest, easiest, and fastest solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to reduce net overseas migration to a level that is below the capacity to supply housing and infrastructure. It is basic logic.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing crisis will worsen.

Yet, here we have Australia’s lying CEOs pretending to care about housing affordability while lobbying for more immigration. Their rank hypocrisy is unbelieveable.

No wonder public trust in the business sector has collapsed.