Over the weekend, I was interviewed by Luke Grant from Radio 2GB/4BC, discussing the current debate over Australia’s housing crisis.

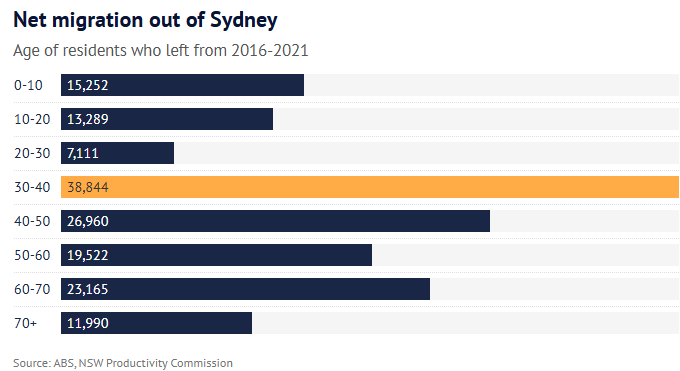

The interview was in response to last week’s impassioned article in The SMH bemoaning that young Sydneysiders were leaving en masse, driven out by exorbitant housing costs.

The article said nearly 40,000 prime-aged residents aged between 30 and 40 left Sydney in the five years to 2021.

NSW Housing Minister Rose Jackson proclaimed that the housing crisis is the state’s most significant issue and said it is the government’s “top priority”.

“We risk being a city with no future”, Jackson said. We risk being a city where young people don’t put down their roots here, they don’t start their families here, they don’t start their businesses here, they don’t make their careers here because of housing”.

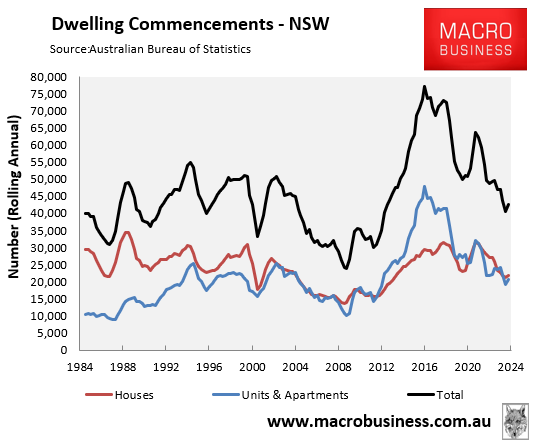

NSW has set an ambitious housing construction target that aims to build 377,000 homes over five years, or 75,400 homes per year.

However, current construction rates are nowhere near this level, with data released last week by the ABS showing that only 42,500 homes were commenced in the year to Q3 2024.

Thus, NSW is lagging in its construction target by 43% or around 33,000 homes.

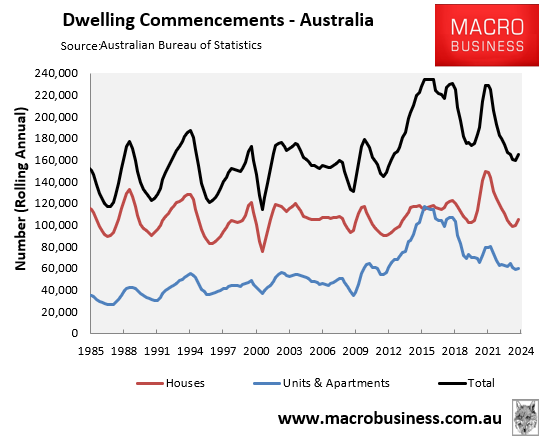

It is a similar situation nationally, where the Albanese government’s target to build 1.2 million homes over five years, or 240,000 homes a year, is running way behind target.

Only 165,048 dwellings commenced construction in the year to Q3 2024, 75,000 (31%) below the required run rate of 240,000 homes.

Australia’s dwelling construction will remain constrained for several reasons.

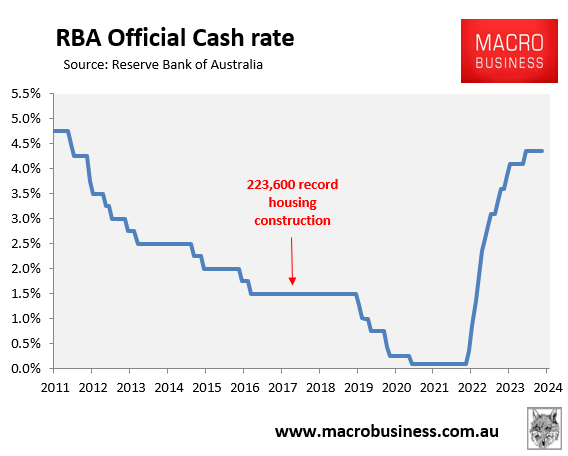

High interest rates have reduced buyer borrowing capacity and made it harder for developers to finance projects.

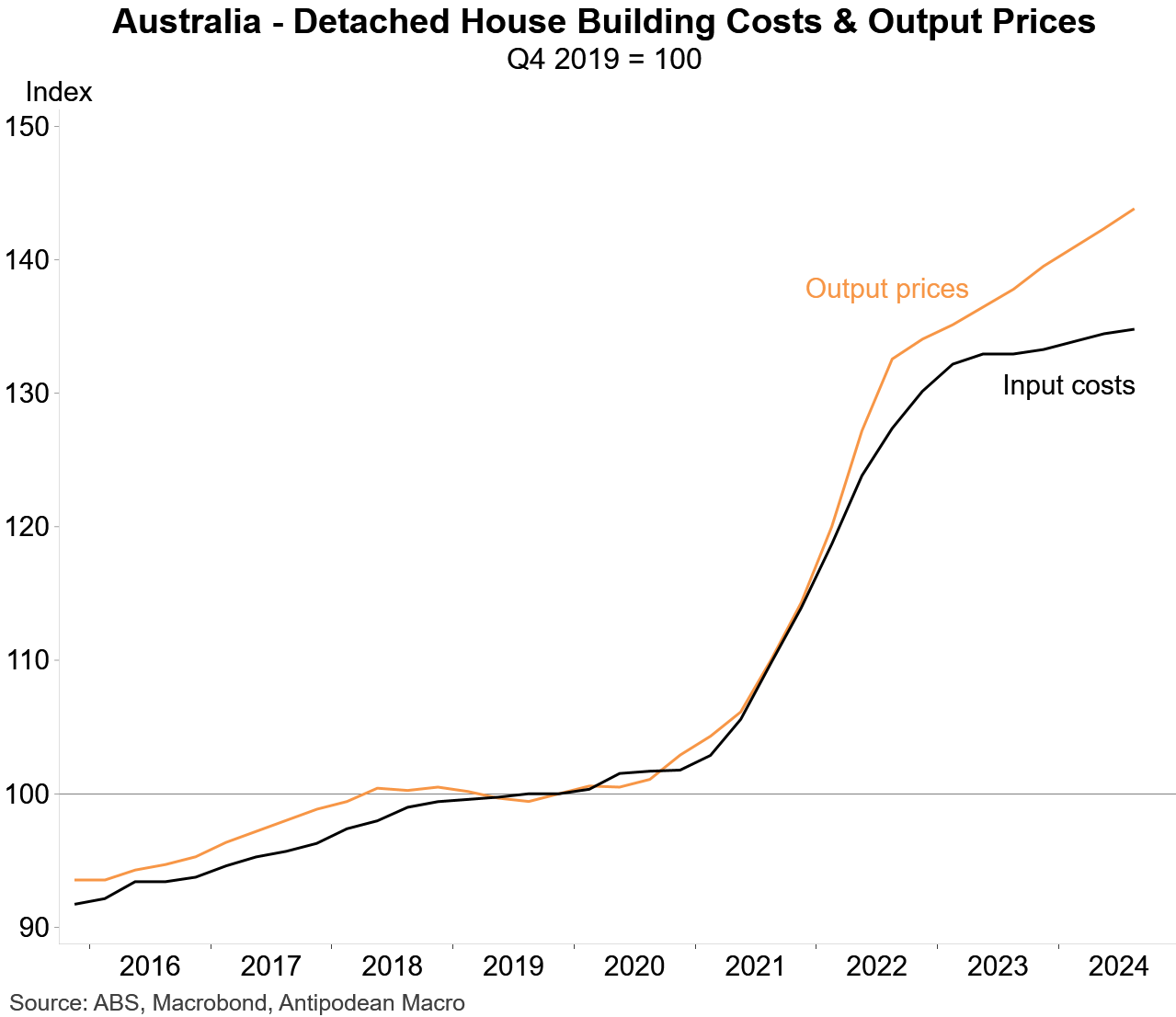

Construction costs have risen by around 40% since the start of the pandemic, pricing projects above what buyers can afford and making projects unfeasible.

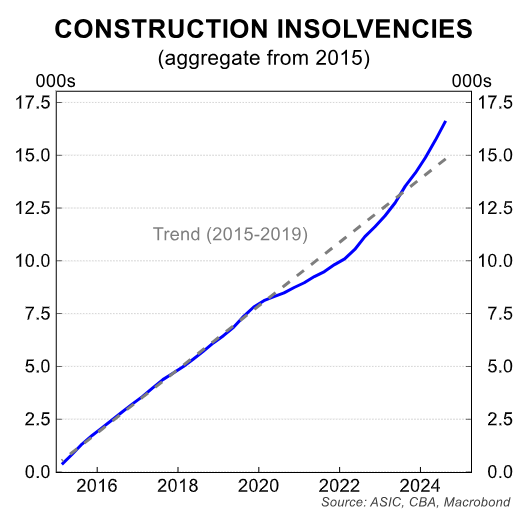

Thousands of home builders have gone bust over the past few years, reducing capacity across the industry.

Finally, builders are competing for workers with government ‘big build’ infrastructure projects.

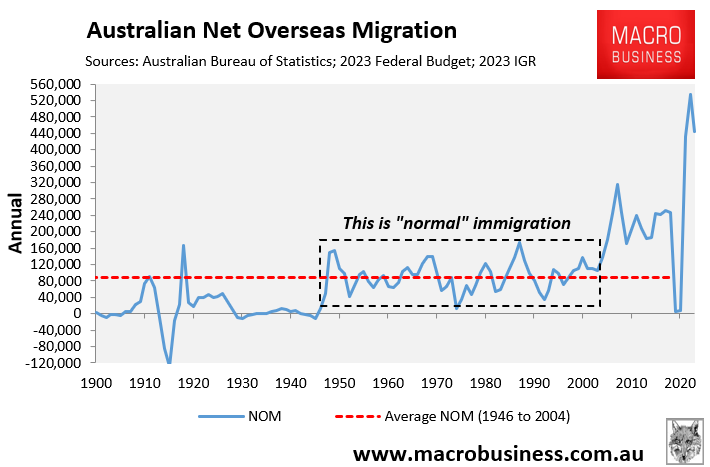

With housing supply constrained, the primary solution to the housing shortage is to reduce population demand by cutting immigration. Otherwise, the shortage will worsen.

As usual, the SMH article and Rose Jackson did not mention lowering immigration; instead, they merely presented Sydney’s housing crisis as a supply problem, not an excessive demand problem.

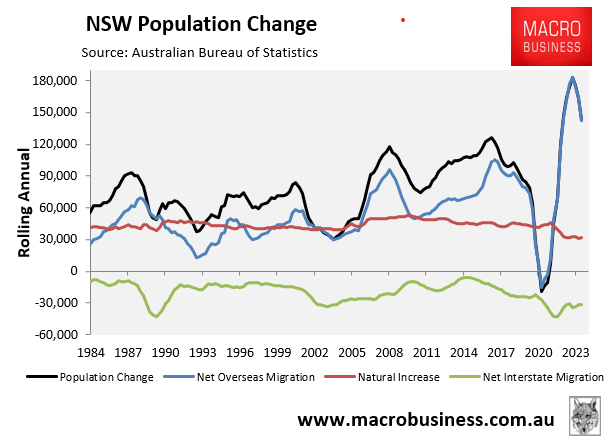

While the SMH bemoaned that NSW lost nearly 40,000 prime-age Sydneysiders in the five years to 2021, NSW added 331,300 net overseas migrants over the same period.

NSW added 142,500 net overseas migrants last financial year alone and has added 1.7 million net overseas migrants this century. Indeed, this century, 81% of NSW’s 2.1 million population growth has come via net overseas migration.

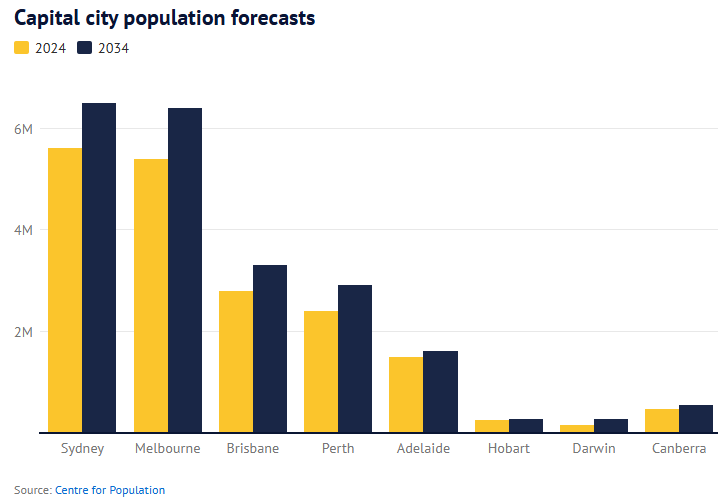

The Centre for Population’s latest projections, released in December, forecast that the nation’s population will balloon by 4.1 million residents over the next 10 years—most of whom will live in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Melbourne is projected to add one million residents over the coming decade; Sydney will add 900,000; and Brisbane and Perth will each add 500,000 residents.

Such a rapid population expansion, driven by net overseas migration, will inevitably worsen housing and infrastructure shortages across Australia.

The projected 410,000 annual population growth—almost equivalent to the population of Canberra annually—will guarantee that population demand forever overruns supply, putting upward pressure on home prices and rents.

The primary solution to the housing crisis, therefore, must be to lower population growth via immigration to a level that is compatible with housing supply.

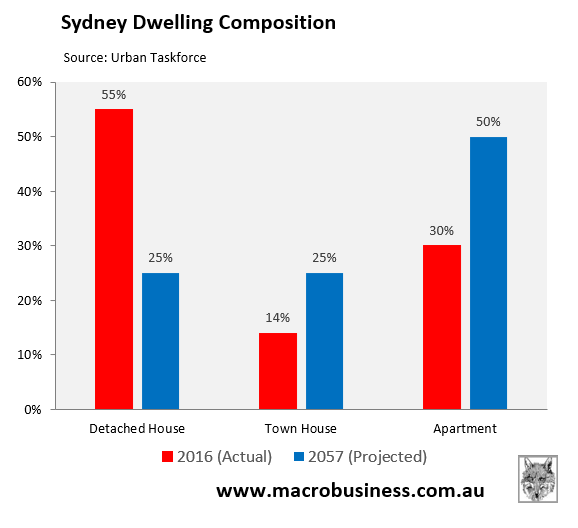

Doing so would also mitigate the need for our future children and grandchildren to live in highrise shoebox apartments.