Last weekend, I was interviewed by Radio 2GB/4BC on Australia’s housing crisis.

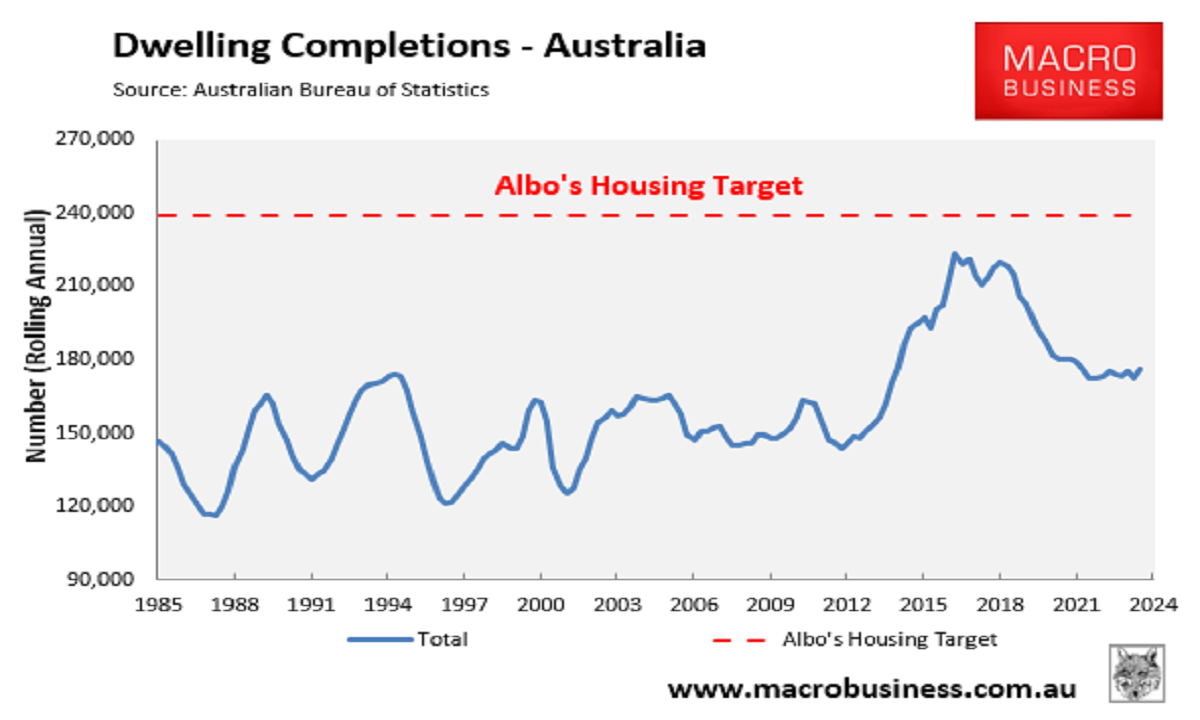

As readers know, the Albanese government has set a target of building 1.2 million homes over five years. This target requires 20,000 homes to be built per month, 60,000 homes per quarter, or 240,000 homes a year.

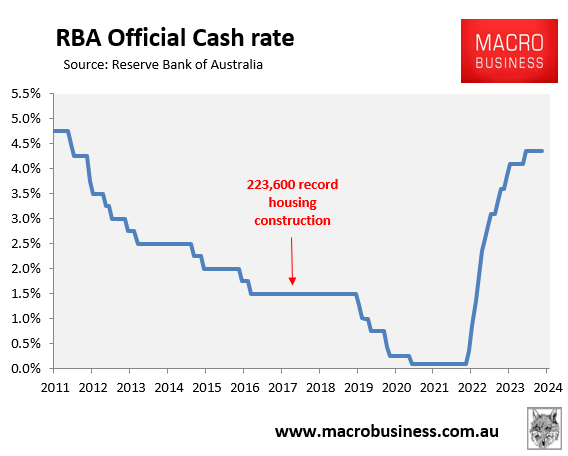

The record 12 month for housing construction in Australia was 223,600, set in 2017 when Australia built many quality high-rise shoebox apartments, riddled with flammable cladding, structural defects, and leaks. The Opal and Mascott Towers were prime examples of this shoddy construction.

Recent NSW government research showed that more than half of recently built apartment complexes suffered from serious defects.

To achieve the Albanese government’s 240,000 a year target, the rate of construction would need to be accelerated, which would likely result in compromised quality and defective apartment buildings.

The current rate of construction is currently tracking way below Labor’s housing target.

Only 176,000 dwellings were completed in the year to June 2024, 64,000 below target.

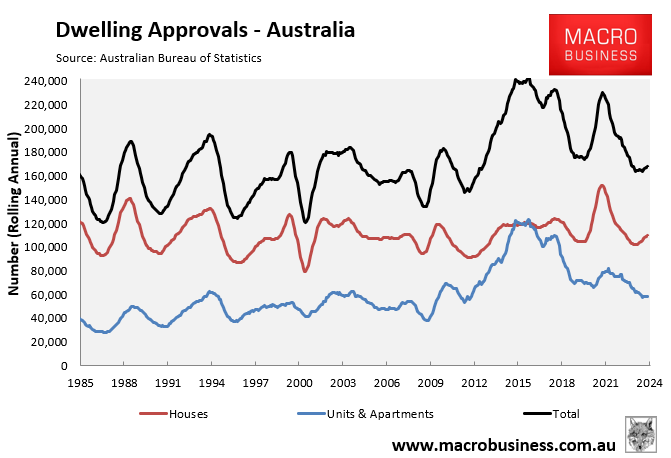

Worse, only 168,000 dwellings were approved for construction in the year to October 2024, 72,000 below the target.

Australia’s government’s solution to the housing crisis is to relax planning to allow the building of higher towers with smaller apartments, fewer carparks, less natural light, and less storage.

However, degrading the quality of apartments by forcing Australians to live in poor-quality shoeboxes is unlikely to solve the problem because the supply side of the housing market is severely bottlenecked by costs and labour shortages.

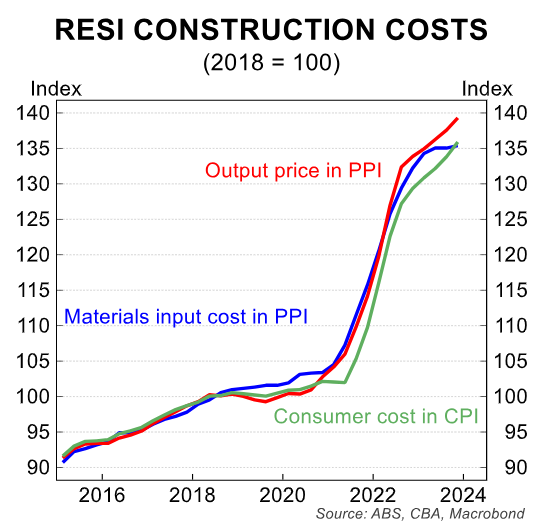

Dwelling construction costs have soared by around 40% since the beginning of the pandemic, making it unprofitable to build apartments.

Australia also has high interest rates. During last decade’s record construction boom, the cash rate was 1.5% versus 4.35% currently.

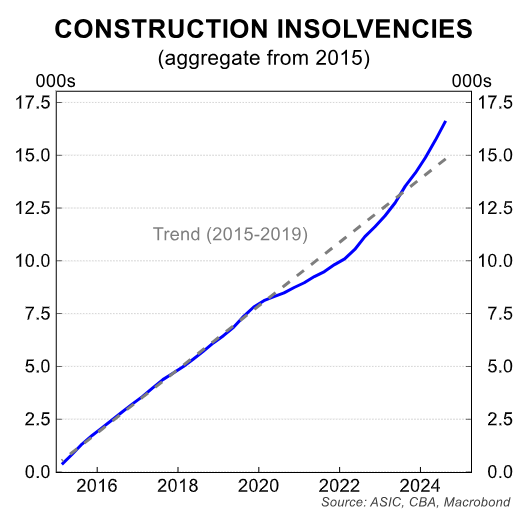

The sector’s capacity has decreased due to the bankruptcy of thousands of home builders.

Home builders are also competing with state government ‘big build’ infrastructure projects for labour.

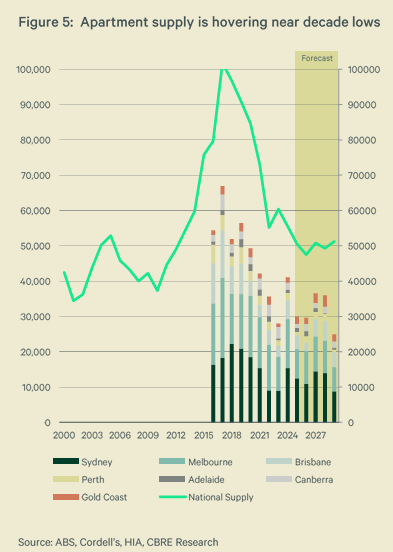

In October, CBRE forecast that Australia would only build around 50,000 apartments annually between 2025 and 2029, around half the level of the 2017 peak.

CBRE said that apartment prices would need to rise by more than 20% to make it profitable for developers to build.

Charter Keck Cramer likewise stated that apartment prices for established stock needed to rise by 15% and new apartment prices would need to rise by 30% to entice development.

However, if apartment prices rose so aggressively, then buyer demand would collapse.

Clearly, the notion that by building lots of apartments, affordability would improve is also false.

The reality is that Australia would not need to transform its cities into high-rise slums if the federal government grew the population slowly via moderate levels of net overseas migration.

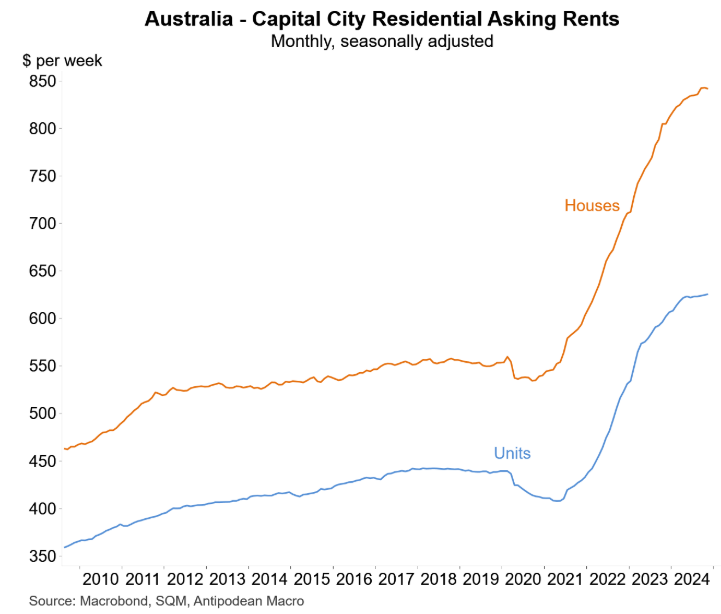

The Albanese government imported around one million net overseas migrants in its first two years in office, creating the current rental crisis.

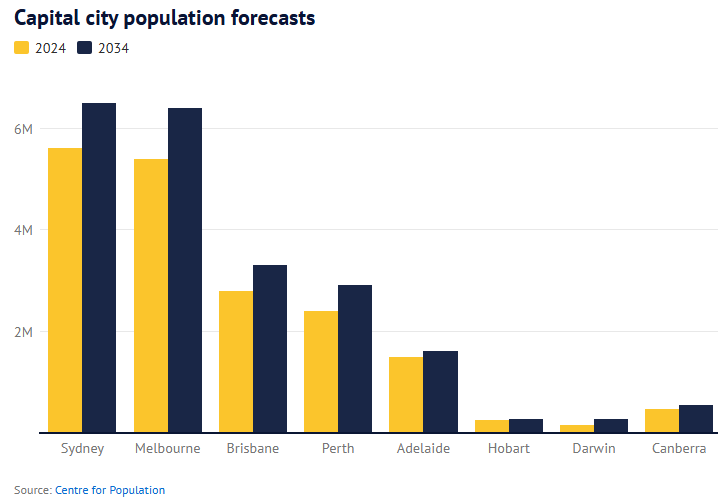

The Australian Treasury’s Orwellian Centre for Population released its 2024 Population Statement before Christmas, which forecast that ongoing high immigration will add 4.1 million residents over the next 10 years—most of whom will live in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Under the population projections, Australia would add nearly a Canberra’s worth of people every year for 10 consecutive years.

Melbourne’s population is projected to swell by one million people over the coming decade, Sydney’s by 900,000 people, whereas Brisbane’s and Perth’s populations are projected to balloon by 500,000 apiece.

Such rapid population expansion, driven almost entirely by strong net overseas migration, will inevitably worsen housing and infrastructure shortages.

The cheapest, easiest, and fastest solution to Australia’s housing supply problem is to reduce net overseas migration to a level that is well below the capacity to supply housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing crisis will continue to worsen.

Australia’s politicians and so-called “experts” paint Australia’s housing crisis as a lack of supply. However, the crisis is primarily a problem of excessive population demand.

Australia will never build enough homes so long as it adds so many people via immigration every year.