Over the past decade, the number of cafes nationwide has reached an unsustainable level, and many are struggling to survive.

I moved to my home suburb of Ashburton, Melbourne, in 2006. At the time, the local High Street shopping strip had only a few cafes.

The number of cafes peaked at around a dozen in 2002-23. This number was never sustainable, as most struggled to attract customers.

Over the past 18 months, several cafes on High Street have closed, and their storefronts remain empty.

For the first time since I moved to Ashburton in 2006, the number of cafes operating is shrinking.

A similar situation is unfolding across Australia.

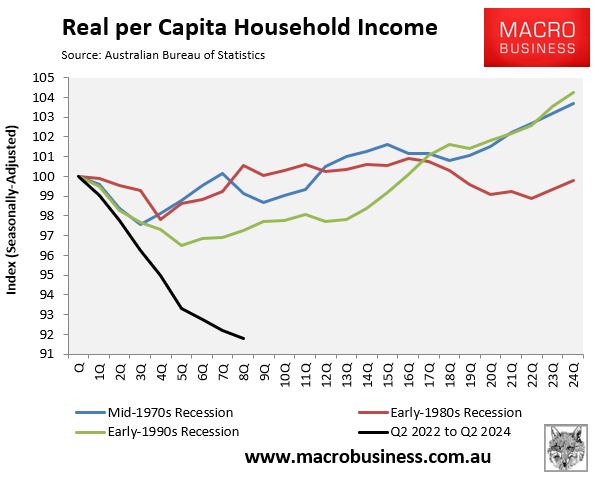

Australians are experiencing a cost-of-living crisis encapsulated by households experiencing their sharpest-ever decline in real disposable incomes.

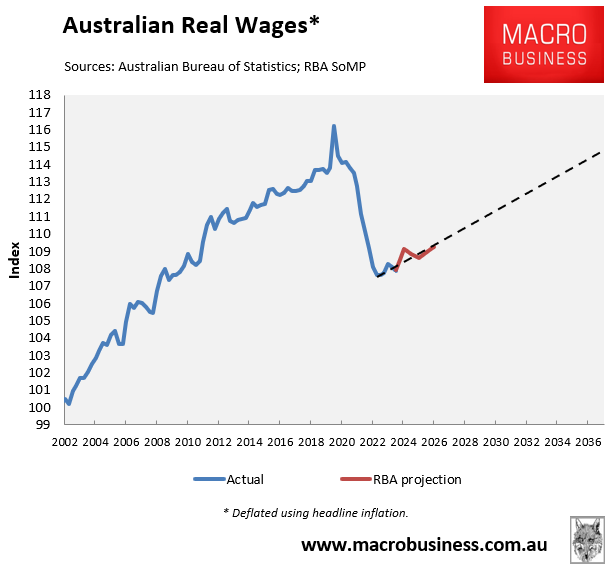

Australian real wages have also collapsed and are not forecast to recover to their former peak for at least a decade.

As a result, Australians are cutting back on discretionary spending and cafes are in the firing line.

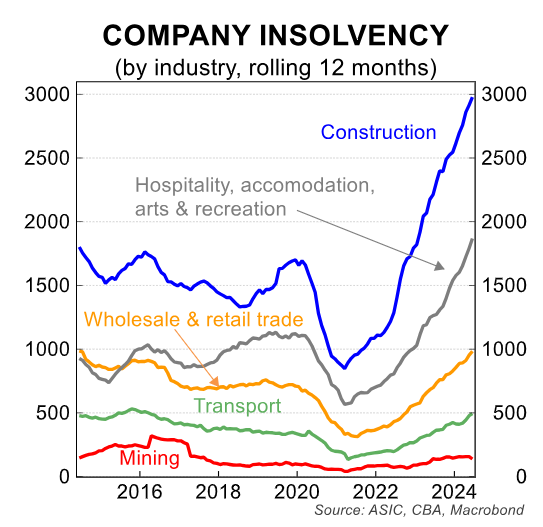

Insolvencies in the hospitality industry are approaching double pre-pandemic levels, indicating the implosion of Australia’s cafe bubble.

The reality is that most Australians cannot afford to spend more than $5 on a coffee or $20 for smashed avocado on toast.

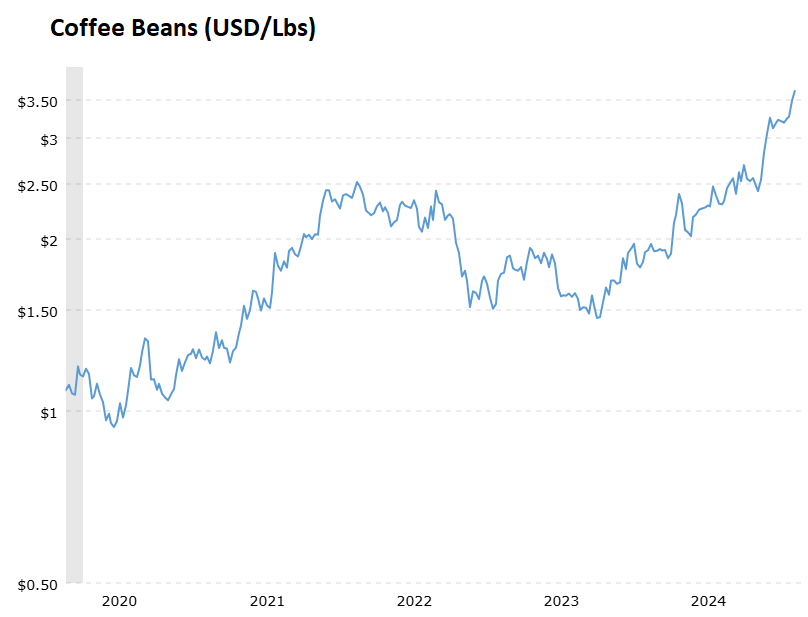

To add further insult to injury, global coffee prices are soaring.

As illustrated in the following chart, the price of coffee beans in USD has more than doubled over the past 15 months. The devaluation of the Australian dollar adds to the pain for Australian cafes.

“The real story is that supply has fallen much faster than demand. It really is that simple”, said Trishul Mandana, managing director for Volcafe, one of the world’s largest coffee traders.

“The tightness in Brazil and the current differentials are telling us the real story of the 24/25 crop – and which will no doubt quickly lead to the disappearance of certs (arabica-certified stocks at ICE). And things could get messy rather quickly”, Mandana added.

Therefore, coffee bean prices are expected to rise further in the months ahead.

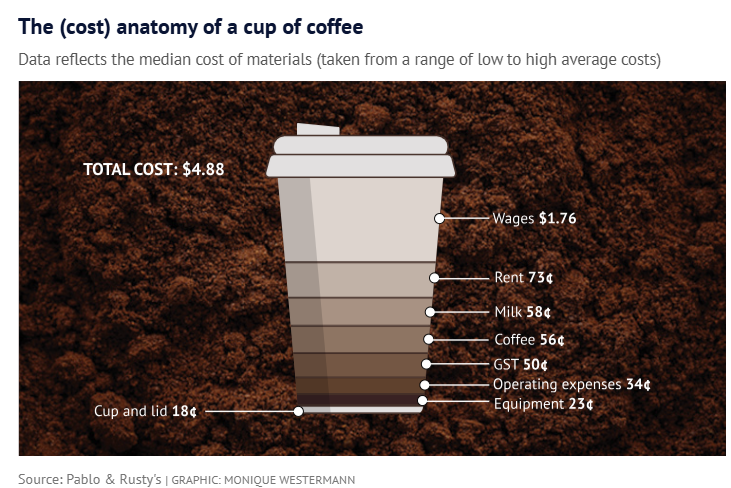

Coffee roaster Pablo and Rusty’s claim the cost of making coffee in Australia has risen to nearly $5:

While coffee beans comprise only around 10% of the retail price of a coffee, further increases will push retail coffee prices higher and compress already wafer-thin cafe margins.

The costs of power, labour, rent, and insurance are also rising, crunching margins.

Pablo & Rusty’s chief executive, Abdullah Ramay, recently warned that the retail price for a coffee must rise to $7 to make it profitable for cafes.

“The cost of this thing should’ve been $7-plus. If you’ve been buying coffee for $4.50 … the cafe’s been subsidising”, he said.

“You should thank your cafe owner and barista; you’ve been getting the bargain of the century”.

However, if retail coffee prices increase to $7, then it will crunch buyer demand, resulting in fewer customers and sales.

“If customers choose to change their coffee habits, this might threaten the Australian coffee industry, which employs almost 70,000 people, as of 2023″, RMIT logistics and supply chain management Professor Vinh Thai warned.

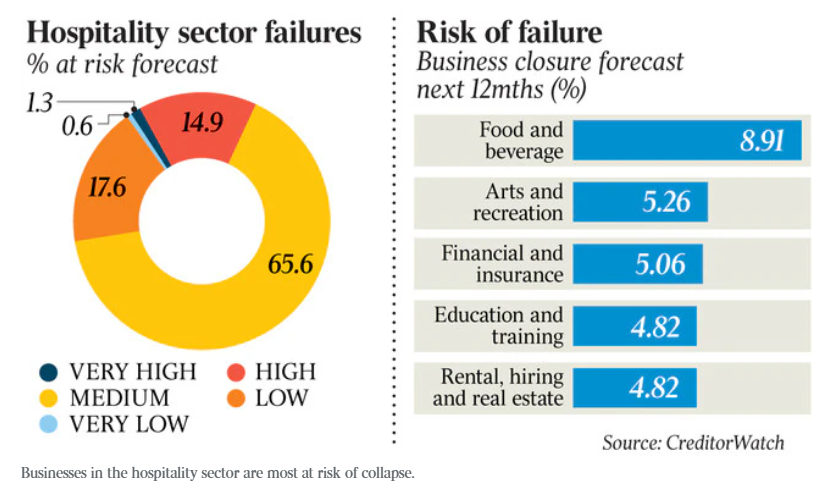

A recent CreditorWatch poll warned that roughly one out of every six (16.2%) hospitality businesses are at a high risk of failing because of high interest rates, rising rents, increased living costs, and the pandemic’s long-term effects.

Nearly 9% of food and beverage businesses are forecast to close over 2025.

Thus, a perfect storm has hit the cafe sector. Buyers are strapped for cash amid falling real incomes and the cost of living crisis.

At the same time, the costs of running cafes and making coffees are soaring.

The upshot is that Australia’s 20-year cafe boom has turned into a bust, with the number of cafes shrinking to match demand.