Alan Kohler penned another article decrying Australia’s housing crisis, which he argues is driven by “lip service, hypocrisy, and an investment culture”.

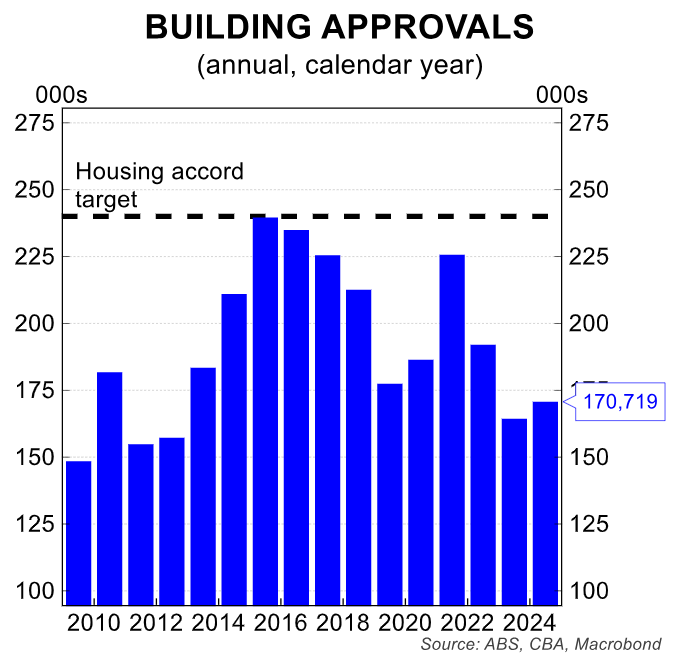

Kohler notes that the Albanese government’s target of building 1.2 million homes over five years is a “lost cause”.

“The number of housing approvals has declined, not increased!”.

“Since mid-2024, when the five years began, there have been 89,734 housing approvals. To meet the 1.2 million approvals target by 2029 from here, there will have to be 21,000 per month, every month, from now on — a 42% increase on the number in December”.

“In other words, the target is no longer an aspiration, it’s a lost cause”.

Kohler also listed the factors behind the inexorable rise in Australian housing values since the turn of the century.

“In 1999 came the final death knell of housing as a “right”, when it became an investment asset after the Howard government halved capital gains tax”.

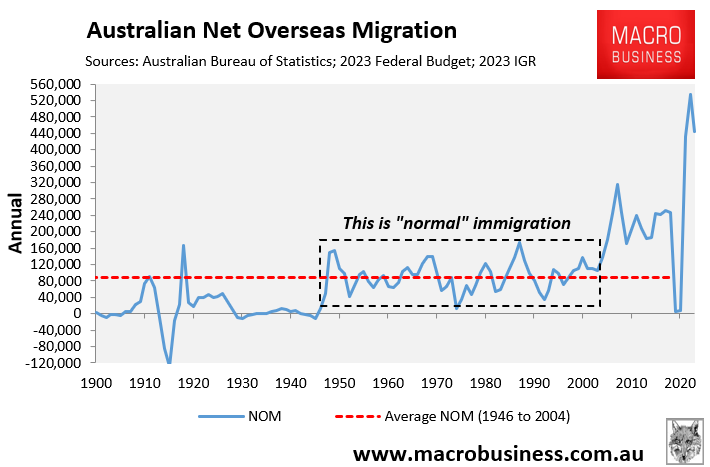

“The appeal of housing as an investment was bolstered by six interest rate cuts in 2001 amounting to 2%, even though there was no recession, and the supercharging of housing demand after 2005 by a doubling, then trebling, of immigration, as a result of changes to student visas in 2001”.

“That 50% capital gains tax discount didn’t make a lot of difference in itself — the increase in benefit between that and the previous CPI adjustment was minimal because inflation was a lot higher then than now”.

“But combined with negative gearing, plus the interest rate cuts of 2001 and the surge in immigration in the late 2000s, it turned housing into the most attractive investment asset since the real estate boom of the 1880s, or the stock market booms of the 1920s, 1960s and 1980s”.

The upshot is that Australian house prices will be pushed even higher when the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) commences its next monetary easing cycle, likely beginning next week.

“CoreLogic last week reported that, largely as a result of this expectation about interest rates, two-thirds of real estate agents expect prices to rise in 2025, and most expect a rise of greater than 5%”…

“Now, we’re going to get another bout of rate cuts with no recession and immigration is back to what it was in the late 2000s, so the eighth improvement in housing affordability (decline in prices) since 1980 will be short-lived”.

Kohler also warned that there are costs associated with densifying suburbs to accommodate more migration.

“The cost of population growth and more affordable housing will be borne by the existing residents of suburbs to be densified, in the form of crowded roads, trains, schools, hospitals, doctors etc”.

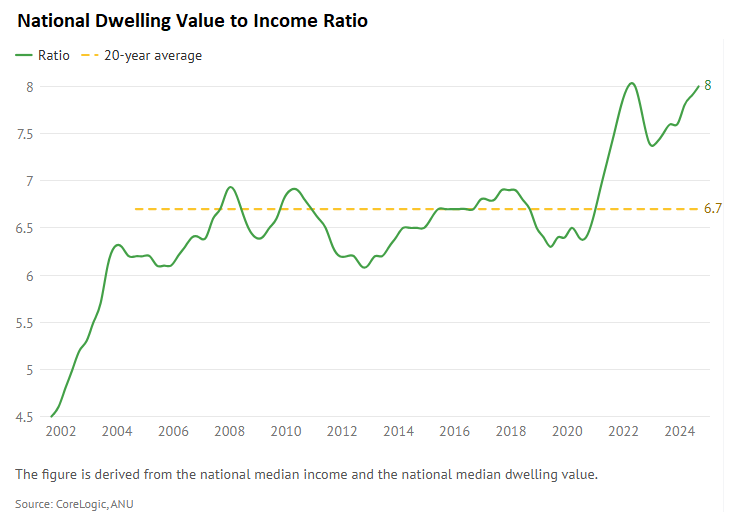

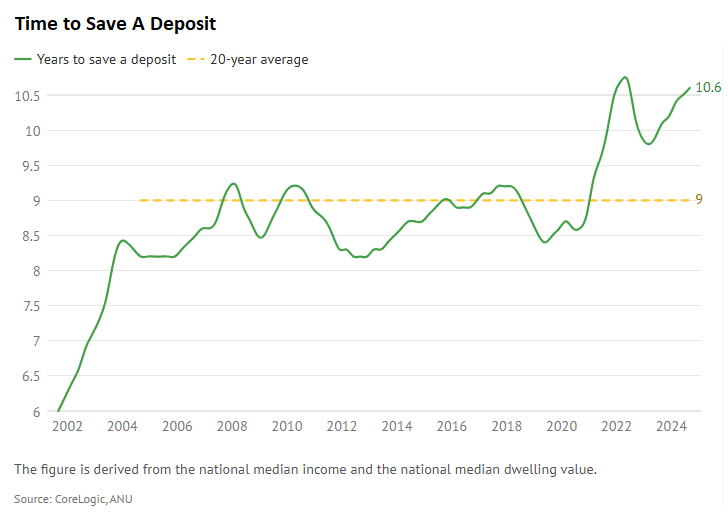

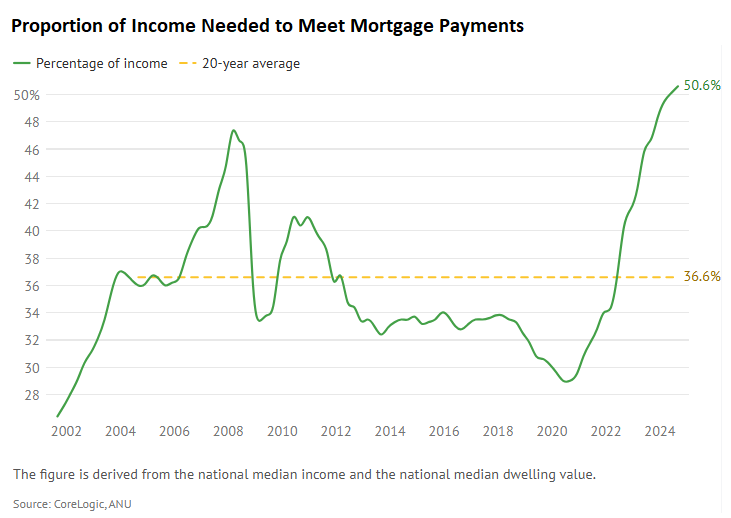

The aggregate data on Australian housing affordability highlights Kohler’s concerns.

The national dwelling value-to-income ratio hit an equal record high of 8.0 in the September quarter of 2024, up from a 20-year average of 6.7.

In the September quarter of 2024, the time it took for the median-income household to save a deposit on a median-priced home was 10.6. While this was marginally below the record high of 10.7 in the June quarter of 2022, it was well above the 20-year average of 9.0.

The share of income the median-income household needs to make mortgage repayments on the median-priced home hit a record high of 50.6% in the September quarter of 2024. It was also well above the 20-year average of 36.6%.

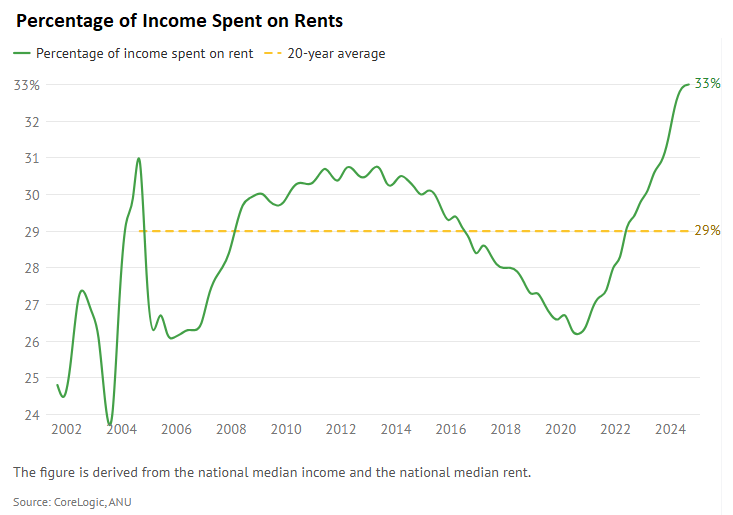

Finally, the percentage of income a median household needed to meet the median rent hit a record high of 33% in the September quarter of 2024. It was also well above the 20-year average of 29%.

The most effective solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to cut net overseas migration significantly.

Excessive immigration has a profoundly negative impact on housing affordability, especially for first-time buyers and renters.

- It directly raises rents, which hurts tenants and makes it more difficult for first-time buyers to save a deposit.

- It drives up property prices, making home ownership even more difficult.

- It forces Australians to live in smaller dwellings (such as shoebox apartments) or further from the city centre.

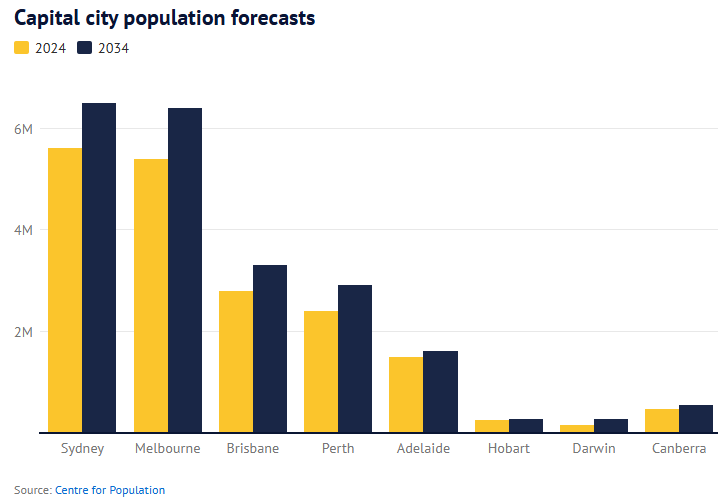

According to the most recent Population Statement from the Australian Treasury’s Centre for Population, the nation’s population will increase by 4.1 million over the next decade, with most of this growth residing in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Melbourne is projected to grow by one million people over the next decade, while Sydney will gain 900,000 and Brisbane and Perth will add 500,000 each.

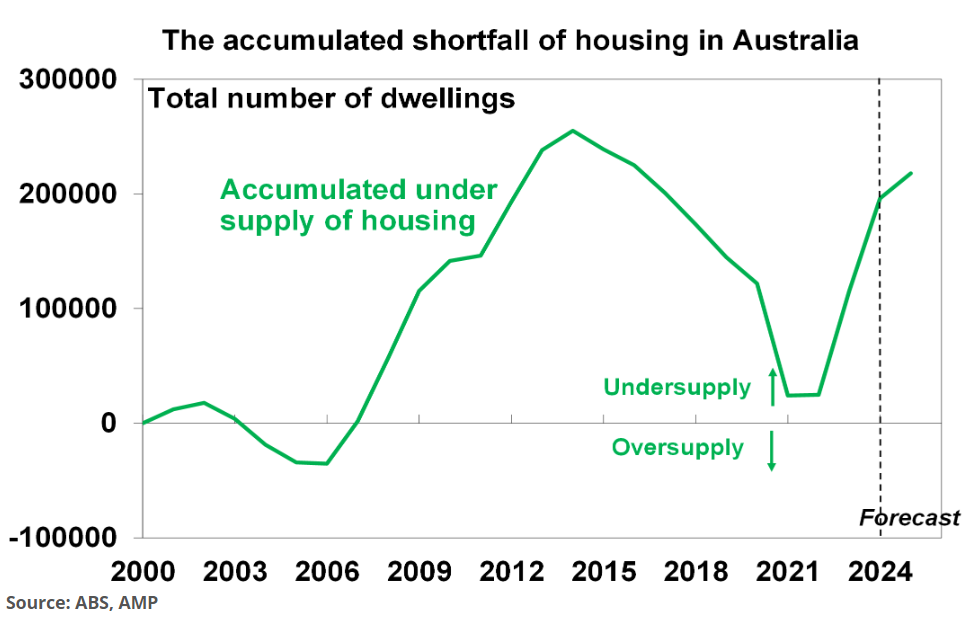

Australia’s housing shortage is already estimated at around 200,000 dwellings.

As a result, Australia’s rapid population increase, driven by net overseas migration, will worsen housing and infrastructure shortages in the major cities.

The projected annual population growth of 410,000—roughly equivalent to Canberra’s current population—will ensure that population demand consistently exceeds supply, putting additional upward pressure on housing rents and prices.

The bottom line is that immigration must be reduced if purchase and rental affordability are to improve sustainably.