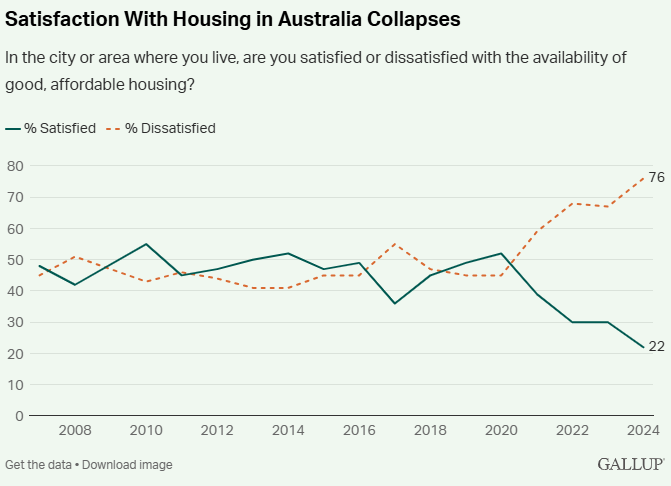

Gallup released a survey in January, conducted across 140 countries with responses from 14,000 people (including 1,000 in Australia), showing that Australians are fed up with unaffordable housing.

Only 22% of Australians were satisfied with home availability in 2024, a record low. In contrast, 76% expressed unhappiness, a discontent rarely seen in high-income countries.

Only 16% of Australians aged 18 to 34 reported satisfaction with housing availability, the lowest level recorded in the country.

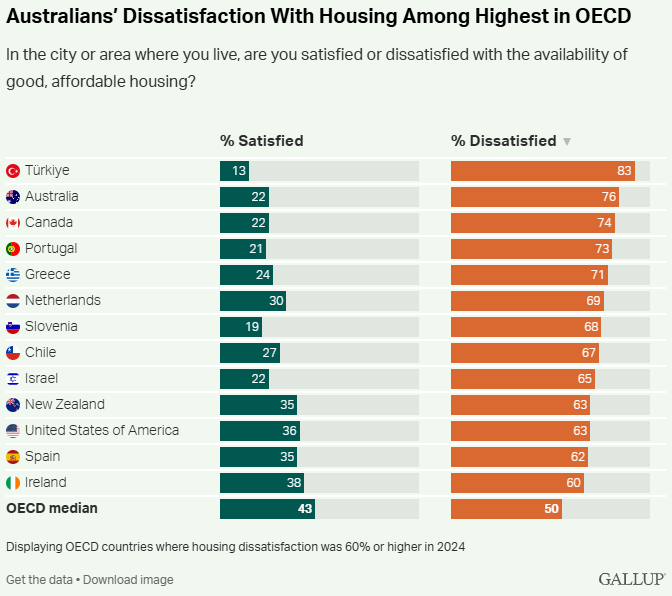

Compared to other high-income countries, Australia has the highest housing discontent.

“The causes of Australia’s current housing crisis are complex”, noted Gallup. “Housing supply is not keeping pace with increasing demand for several reasons, including historic underinvestment in public housing, high levels of immigration, and pandemic-related delays in construction”.

“As such, Australia has developed a significant housing deficit in recent years, and its housing stock lags below the average for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries”.

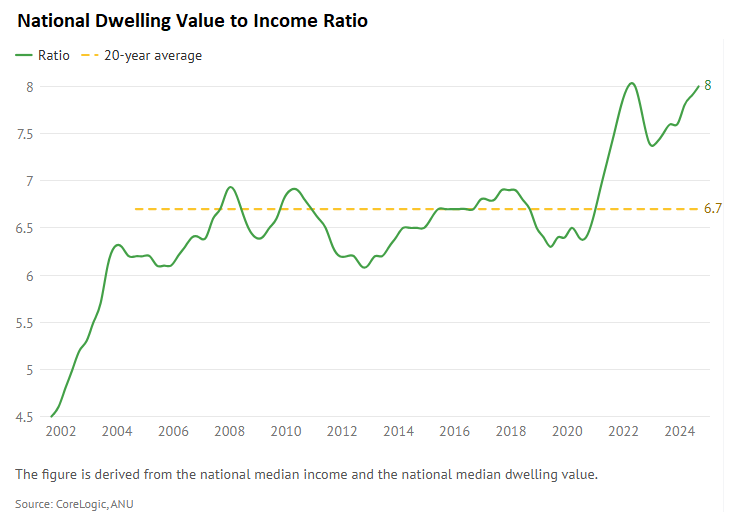

“The rising affordability crisis is stark. Between 2002 and 2024, the house price-to-income ratio almost doubled, with the average house in Australia now costing nearly nine times the average household income. Rent has more than doubled over a similar period”.

“The result is a limited and expensive choice of housing options, which affects younger people and low-income households the most, as they have fewer economic resources to combat the hike in prices”, Gallup reported.

The data on Australian housing affordability is horrible on every level.

First, the national dwelling value-to-income ratio was 8.0 in the September quarter of 2024, up from a 20-year average of 6.7.

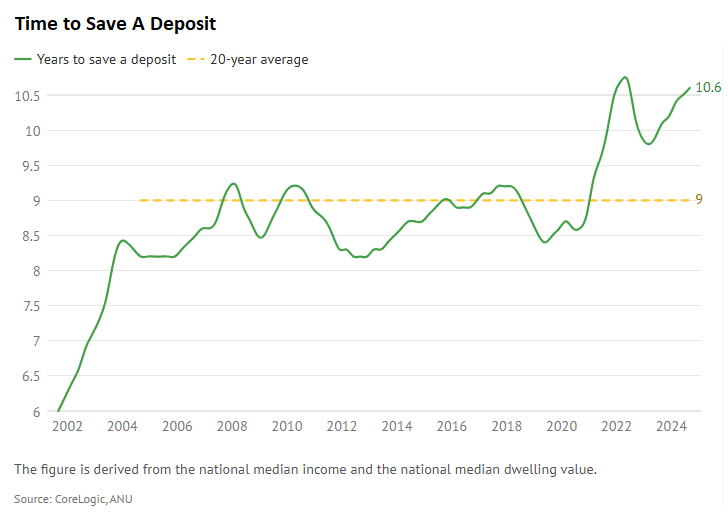

Second, in the September quarter of 2024, the time it took for the median-income household to save a deposit on a median-priced home was 10.6.

Although this was slightly below the record high of 10.7 in the June quarter of 2022, it was well above the 20-year average of 9.0.

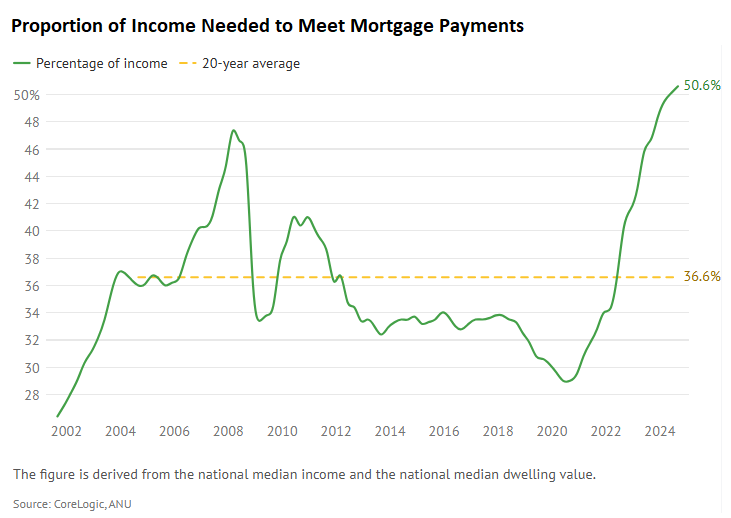

Third, the share of income the median-income household needs to meet mortgage repayments on the median-priced home hit a record high of 50.6% in the September quarter of 2024.

It was also well above the 20-year average of 36.6%.

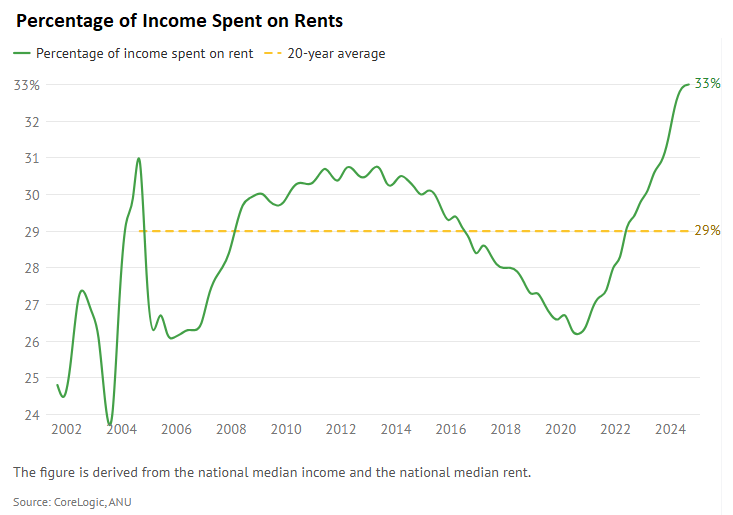

Finally, the share of income a median household needed to pay the median Australian rent hit a record high of 33% in the September quarter of 2024. This was also well above the 20-year average of 29%.

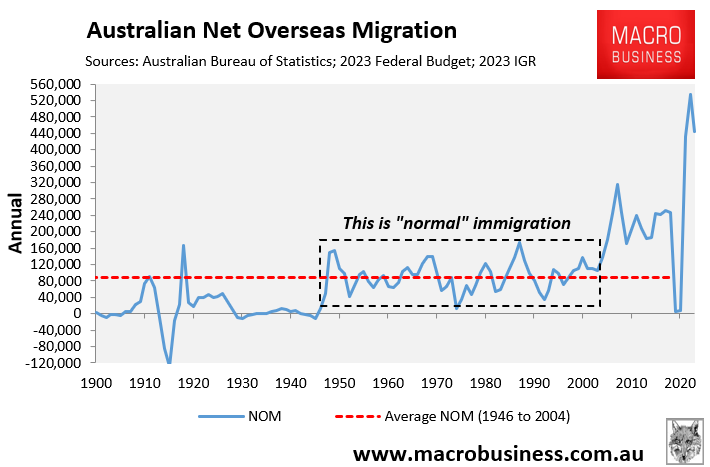

The number one solution to Australia’s housing affordability crisis is to lower net overseas migration significantly.

Excessive immigration is especially deleterious for housing affordability, and first-time buyers and renters in particular, for three reasons:

- It drives up rents directly, negatively impacting tenants and making it more difficult for prospective first-time buyers to save a deposit.

- It puts upward pressure on home prices, making homeownership even more difficult.

- It forces Australians to live in smaller homes (e.g., shoebox apartments) or farther from the city centre.

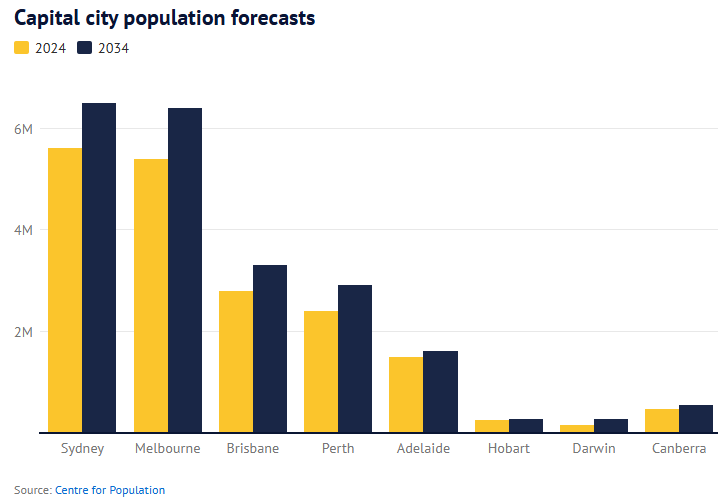

The most recent Population Statement from the Australian Treasury’s Centre for Population, released in December, says Australia’s population will balloon by 4.1 million over the next ten years. Most new residents will settle in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Perth.

Melbourne is projected to add one million residents over the next decade; Sydney will add 900,000; and Brisbane and Perth will add 500,000.

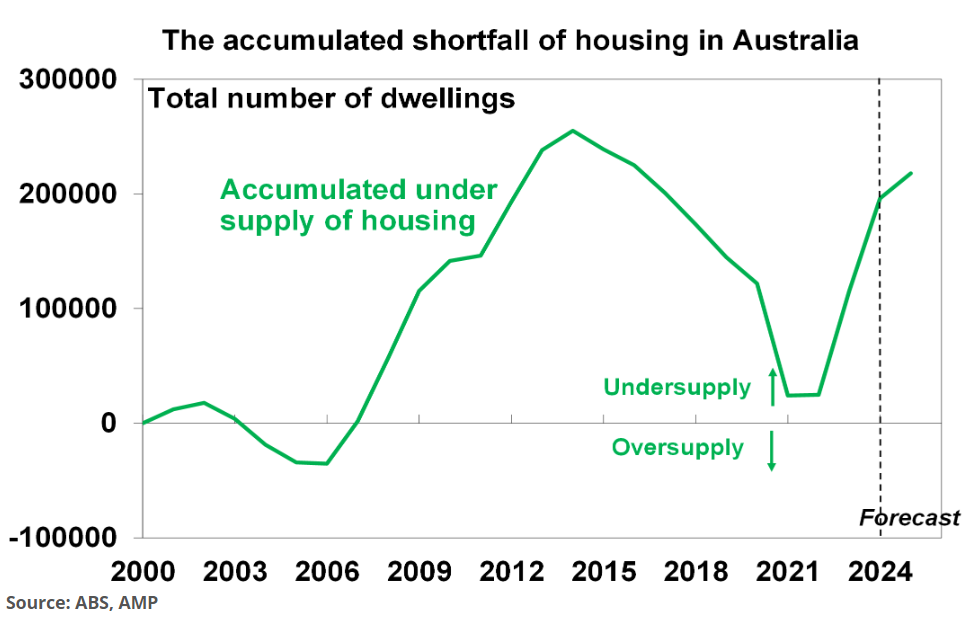

Australia already has a shortfall of more than 200,000 homes, according to AMP.

Such strong population growth, driven almost entirely by high net overseas migration, will exacerbate housing and infrastructure shortages in Australia’s major capital cities.

Australian voters also oppose the projections of the Centre for Population.

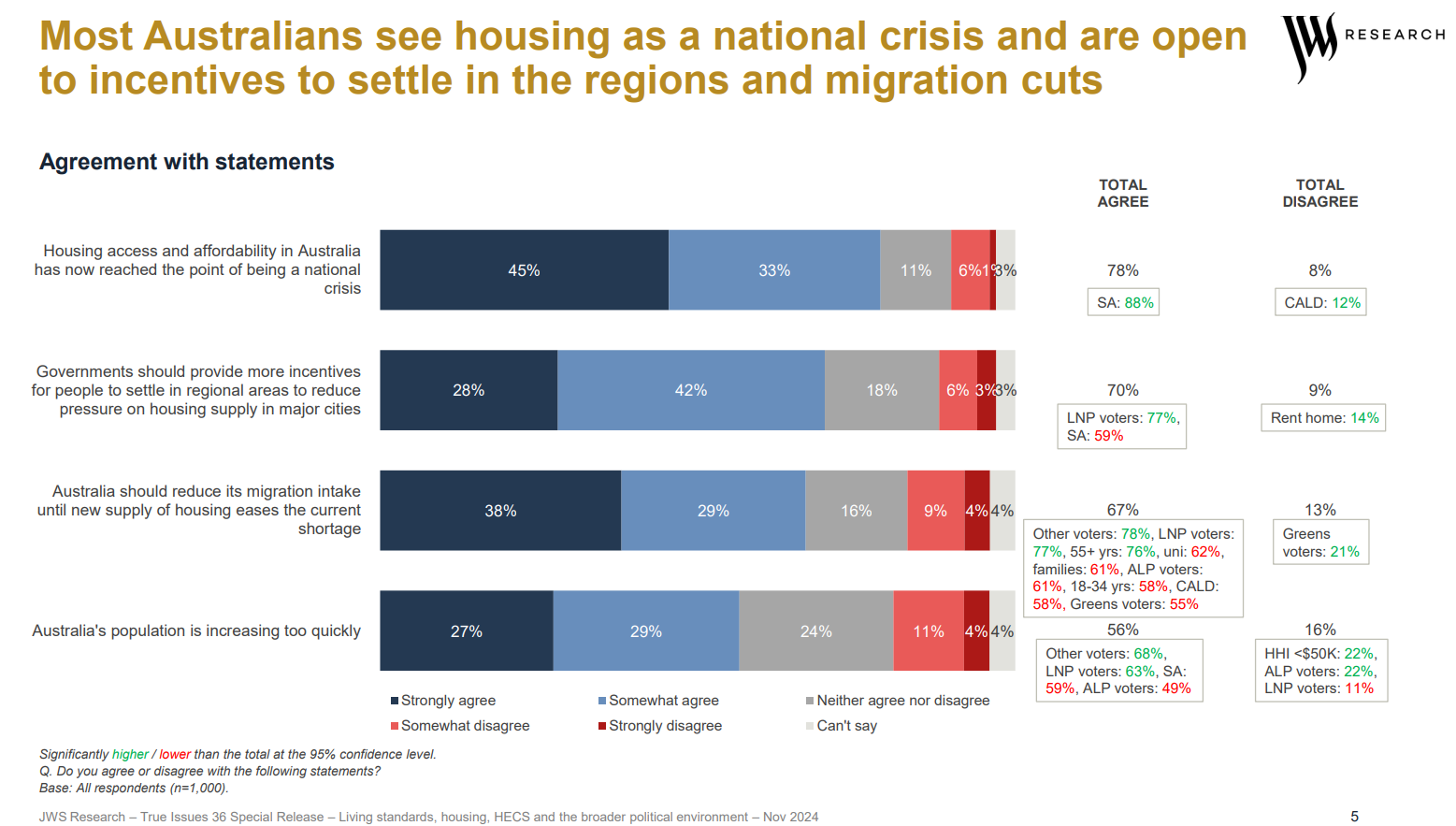

November’s True Issues survey by JWS Research showed that 78% of respondents agreed that “housing access and affordability has now reached the point of being a national crisis”.

Three-quarters (67%) of respondents believed that “Australia should reduce its migration intake until new supply of housing eases the current shortage”. More than half (56%) also believe that “Australia’s population is increasing too quickly”.

Source: November 2024 JWS True Issues Survey

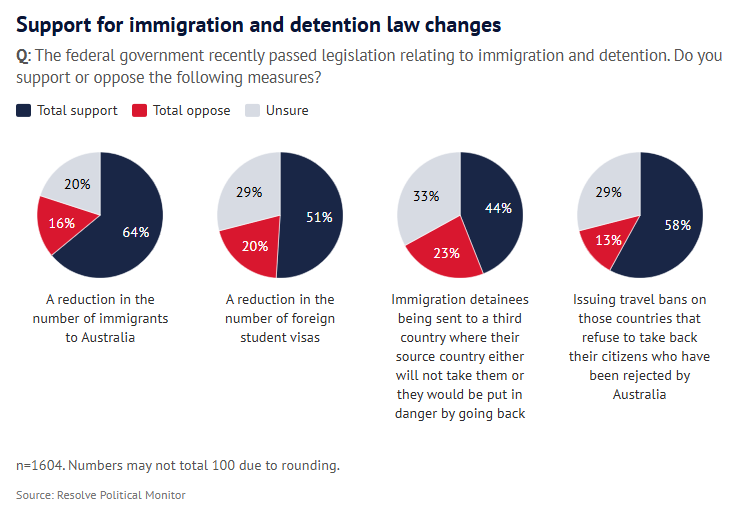

Recent polls by Resolve Political Monitor likewise showed that 64% of respondents wanted “a reduction in the number of migrants to Australia” whereas only 16% opposed this view.

Just over half (51%) of respondents also wanted “a reduction in the number of foreign student visas”, whereas only 20% were opposed.

Sadly, Australia’s politicians have no appetite to lower net overseas migration to sensible and sustainable levels.