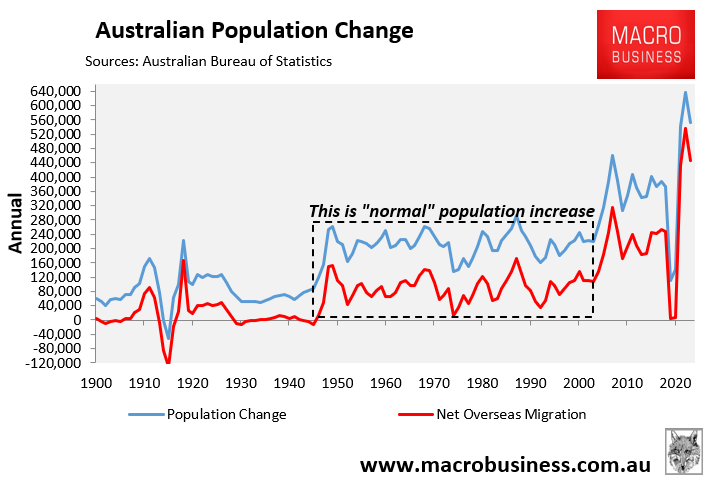

Australia has grown its population by around 8.5 million this century, driven by historically high net overseas migration, most of which is purportedly skilled.

However, Australia’s skills shortages are supposedly worse than ever despite the surge in’ skilled’ migration. How could that be?

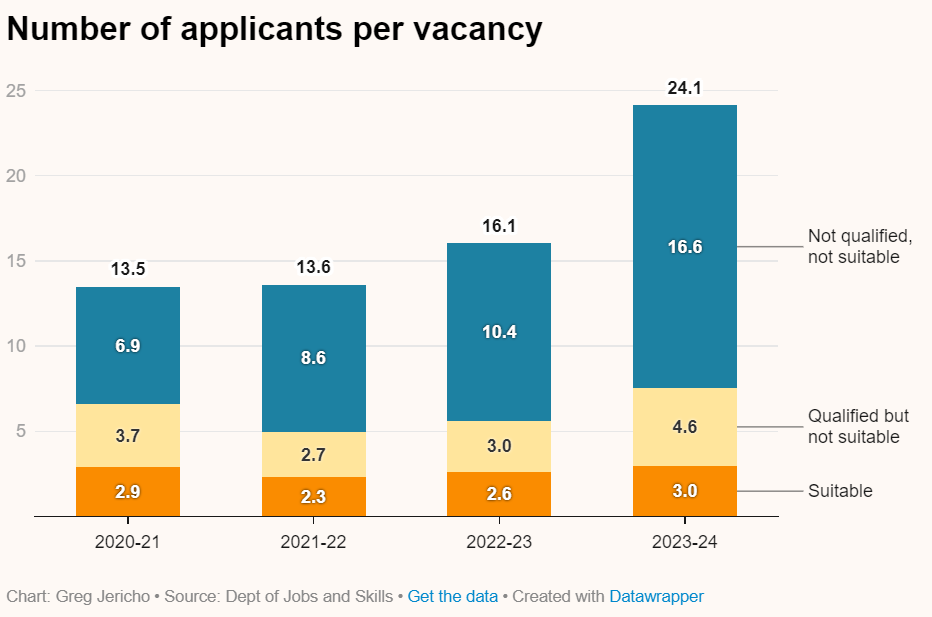

Greg Jericho from The Guardian released research in October 2024 showing that “we still have very high skills shortages” despite record levels of migration.

Jericho showed that these shortages were not because we lacked applicants, which have swelled in number. “There are a lot more people applying for each job”.

Rather, it was because there was a lack of “qualified and suitable candidates applying for jobs”:

It turns out that most of Australia’s so-called skilled migrants work in lower-skilled areas unrelated to their area of qualification.

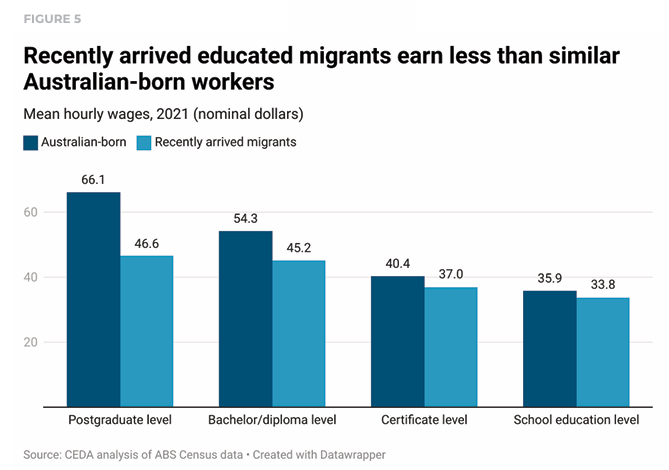

Last year, the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) presented an analysis of the latest Census showing that Australia’s so-called skilled migrants are chronically underemployed and underpaid.

“Recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers, and this has worsened over time”, CEDA senior economist, Andrew Barker said.

“Many still work in jobs beneath their skill level, despite often having been selected precisely for the experience and knowledge they bring”.

The CEDA report also suggested that Australia’s migration system could be dragging down productivity.

“Labour productivity and wages are closely linked, indicating that migrant labour is not being used as productively as it could be”, the report said.

“This decade, migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”.

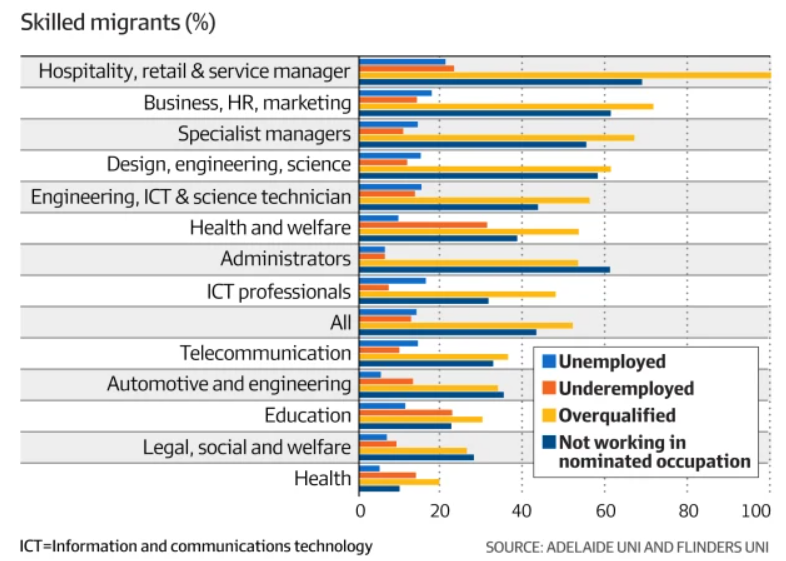

Research from Adelaide University’s George Tan showed that 43% of skilled migrants who used the state-government-sponsored visa system were not engaged in their nominated occupation.

The vast majority of skilled migrants worked in retail, hospitality, and service management and were overqualified for their positions.

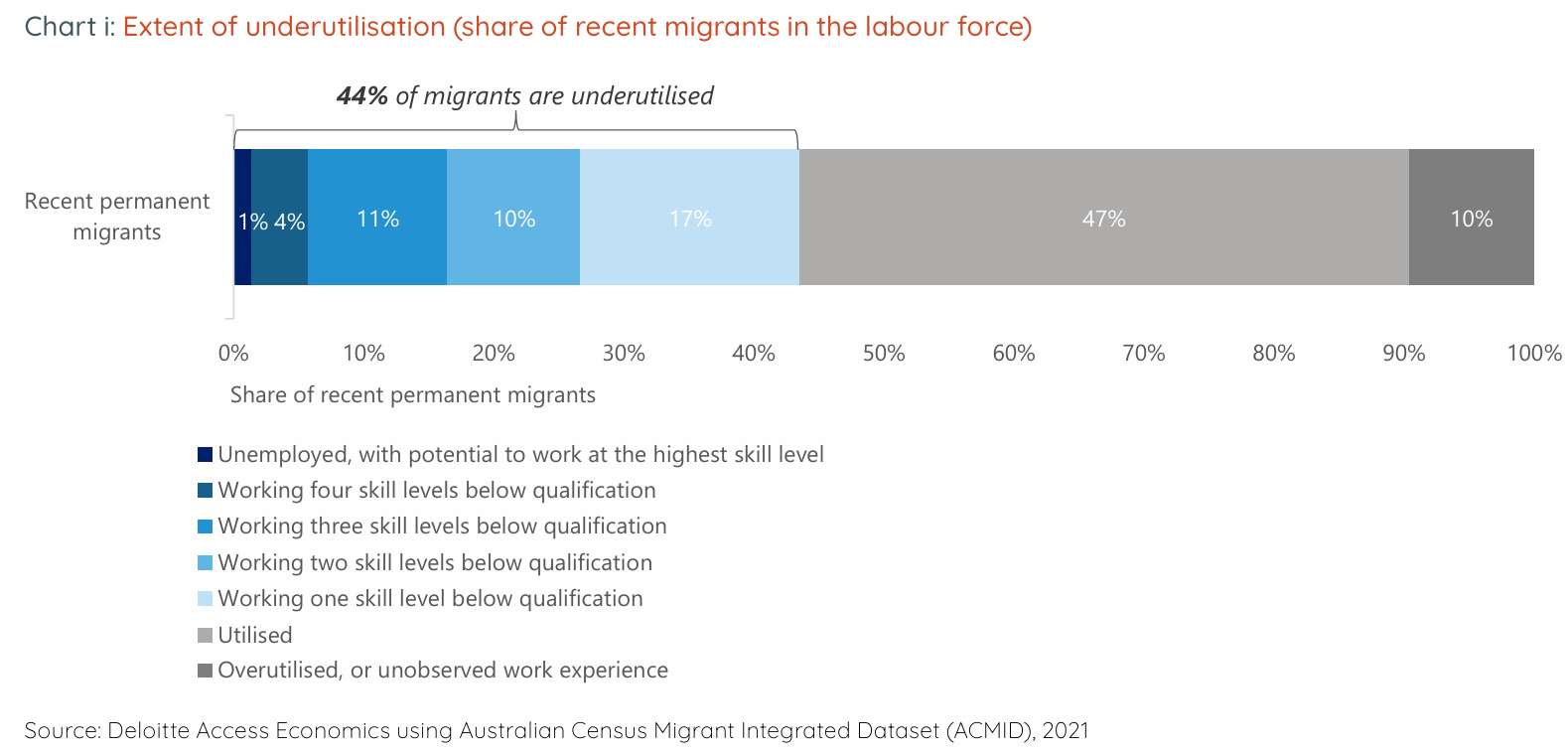

Research undertaken by Deloitte Access Economics on behalf of refugee advocacy organisation Settlement Services International found that 44% of permanent migrants in Australia were working in jobs below their skill level in 2023. Most of these underemployed migrants also entered via the skilled stream.

Specifically, Deloitte estimated that more than 620,000 permanent migrants work below their skill levels and qualifications. Of these, about 60%, or 372,000, arrived in the skilled migration system.

On average, among those permanent migrants who arrived in Australia in the last 15 years, almost half (44%) are working in an occupation at a lower-skill level than is commensurate with their qualifications (Chart 1).

This means in 2024, there are more than 621,000 permanent migrants living in Australia who are underutilised and not working to their full potential.

Despite the permanent migration program’s focus on attracting overseas qualified professionals with skills in demand that address labour shortages, almost six in ten underutilised permanent migrants in Australia entered via the skills stream.

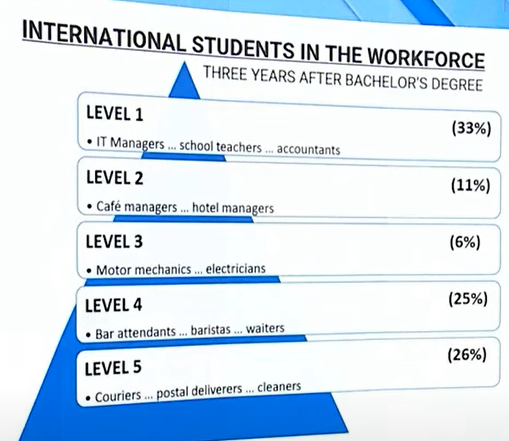

The 2023 Migration Review from the federal government revealed that 51% of foreign-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review (2023)

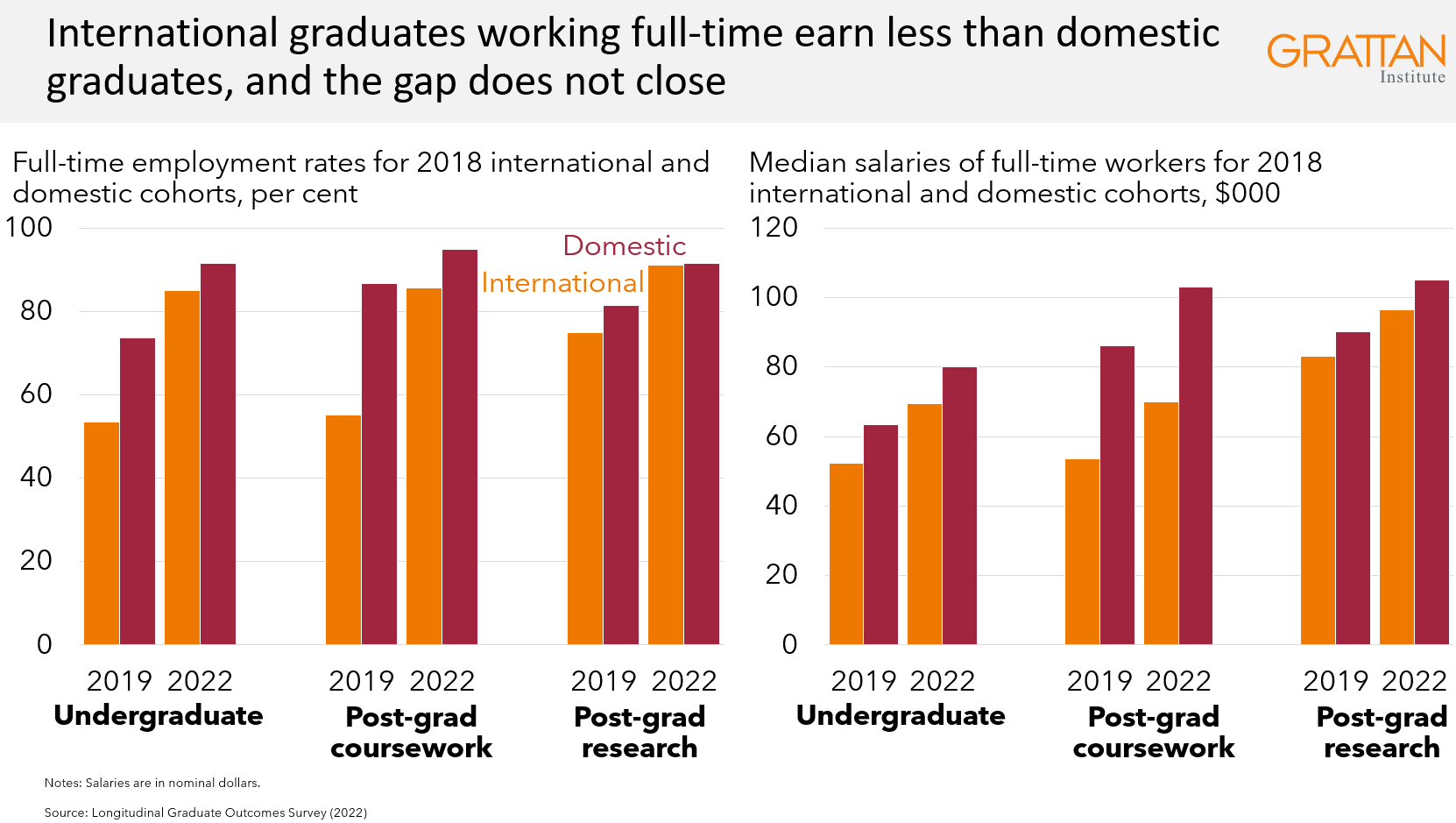

The Graduate Outcome Survey also consistently shows that student graduates earn far less than local-born graduates and have worse labour market outcomes:

This week, The Guardian published an article claiming that “a disconnected, complex and costly system for recognising overseas qualifications is blamed for preventing or delaying skilled migrants working in their chosen field in Australia”.

Accordingly, “a broad coalition of organisations spanning unions and employer groups is ramping up pressure on the major parties to fix the “skills mismatch” to unlock an estimated $9 billion in economic benefits”.

“More than 201,000 of those migrants are qualified in management and commerce, in excess of 80,000 are qualified engineers and just under 50,000 are trained health professionals”, the article claims.

“Creating a national governance body in charge of all skills assessment and qualifications recognition is among the campaign’s recommendations, along with offering means-tested financial help to applicants and setting up information centres in areas with high migrant populations”.

While better utilising the skills already in Australia is a no-brainer, one must ask the obvious question: Why is Australia running such a large permanent skilled migration program when nearly half of the migrants that we import are not actually qualified to work in the field in which we imported them?

Surely, the optimal solution is to run a smaller, higher-skilled, and higher-paid migration system?

The minimum salary threshold on all skilled visas should be set at a level well above the median full-time salary (currently around $90,000). All skilled visas should also be employer-sponsored so that skilled migrants enter jobs in their field of qualification as soon as they arrive.

The malfeasance of Australia’s ‘skilled’ migration system cannot be overstated. We are depriving poor nations of their talent while exacerbating skills and housing shortages at home. The situation is unfavorable to both parties.