Andrew Boak of Goldman Sachs should be RBA governor.

Although he is not a liar, so that rules him out.

On unemployment.

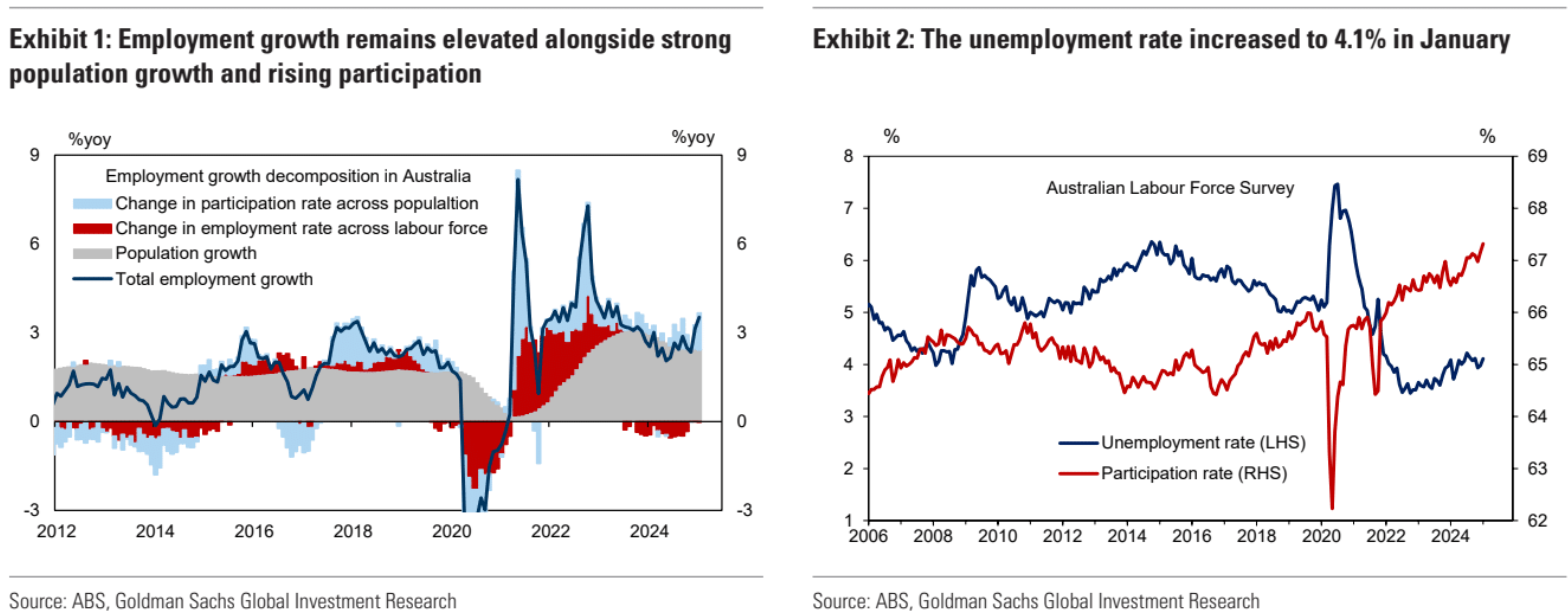

The upside surprise in employment and participation suggests the unusual post-pandemic increase in workers changing jobs or taking extended leave over the summer holiday period is normalizing back to pre-pandemic trends earlier than we expected.

Looking through the seasonal volatility, the data are consistent with our view that Australia continues to experience a migration-led labour supply shock, which is boosting employment and participation but putting downward pressure on wages growth.

This dynamic is consistent with the downside surprise in yesterday’s Wage Price Index, as well as the recent easing in wage-sensitive CPI items.

It is if you have intellectual credibility. It is not if you are paid to lie to protect the immigration-led labour market growth economic model, such as the RBA is.

More from Boak. This time on crashing wages.

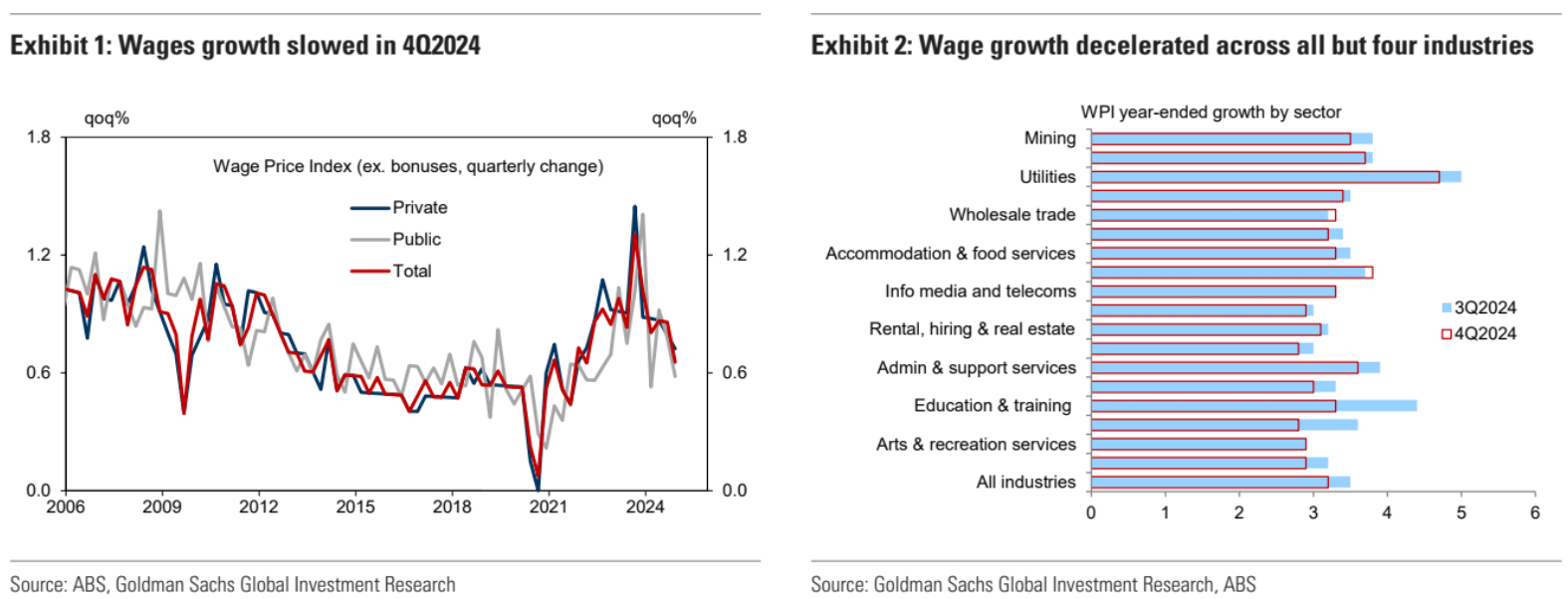

Australia’s Wage Price Index (ex. bonuses) increased 0.65%qoq in 4Q2024, well below expectations (GSe/BBG: 0.8%qoq) and marking the smallest increase since 1Q2022.

Year-ended growth eased 30bps to 3.2%yoy.

The details of the report were soft, with private-sector wages increasing 0.72%qoq (GSe: 0.9%qoq) and public-sector wages increasing 0.58%qoq (GSe: 0.8%qoq).

While part of the easing in sequential growth reflected fewer people receiving wage adjustments, wage growth for those receiving adjustments continued to slow.

Overall, the soft outcome is consistent with our view that the labour market is no longer adding to inflationary pressures in Australia, in part due to a positive labour supply shock.

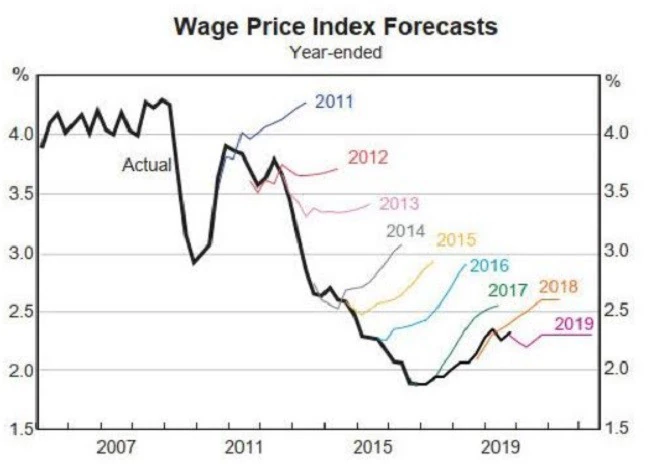

Wages are going back to 2-handle with a bullet. That is lowflation territory.

Finally, Boak’s explanation of why the data is distorted is excellent.

Looking at the labour market, some indicators like employment growth, labour force participation and job vacancies do remain strong and appear to work against the case for easier monetary policy – however, our analysis highlights three reasons why these measures are overstating the current strength of labour market conditions and reconcile with the observed sharp deceleration in wages growth (Exhibit 5) and inflation.

First, the post-pandemic immigration surge boosted labour supply, and this increased overall employment but put downward pressure on wages growth (Exhibit 6).

Second, Australia’s unique wage-setting mechanisms limits the ability of many workers to bargain for higher nominal wages in response to surging global inflation, resulting in an increase in labour market churn and the stock of unfilled vacancies – while simultaneously reducing the usefulness of job vacancies as an indicator of labour demand and wages growth (Exhibit 7).

And third, we estimate that around 40% of the 500k ‘social assistance’ jobs created in connection with the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) reflect an ‘informal to formal’ employment measurement issue rather than an actual increase in labour activity (Exhibit 8).

In view of these three caveats, we put more weight on other indicators pointing to a softening in labour market conditions in Australia, consistent with the signal from weak GDP growth and easing inflation pressures.

The immigration-led, labour market expansion growth model does not do wage growth or inflation.

How long does it take 400 paid-to-lie central bank economists to change a light bulb?

Forever.