As Westpac illustrates, the RBA’s wage fgrowth outlook is ridiculous.

In the December quarter, the Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.7% which at three decimal places was just 0.654%, a whisker off rounding down to 0.6%. This result is going to make it much harder for the RBA to achieve their June 2025 forecast of 3.4%yr when the current six-month annualised pace is already down to 3.1%yr.

If we are generous and allow a 1.0% increase in the March quarter, this still means the WPI must print 0.9% in the June quarter to achieve the RBA’s forecast.

Westpac doubts very much, even with the announced and negotiated wage increases in the public sector, that such an outcome can be achieved when we are already seeing wage inflation easing in the private sector. Private sector wages grew 0.7% in the quarter while public sector wages lifted 0.6%. It worth noting that the private sector/public sector split of the economy-wide wage bill is roughly 75/25, so if private sector wages were to lift 0.8% in the March quarter, public sector wages would have to increase by 1.7% in the quarter in order to hit a 1.0% lift in the total WPI. This would be the largest quarterly increase in public sector wages ever seen in the history of the WPI, the largest being 1.4% in December 2023.

While it is possible that recent increases in public sector wages present an upside risk to our March quarter forecast of 0.7%, the data released today presents a meaningful downside risk to the RBA’s forecast of 3.4%yr at June 2025.

As such, we retain our forecast for the annual pace of the WPI to be down to 3.0%yr at June 2025, 0.4ppt below the RBA’s forecast.

Recall Andrew Boak at Goldman who has had the intellectual integrity that the RBA lacks in explaining why wage growth is caput.

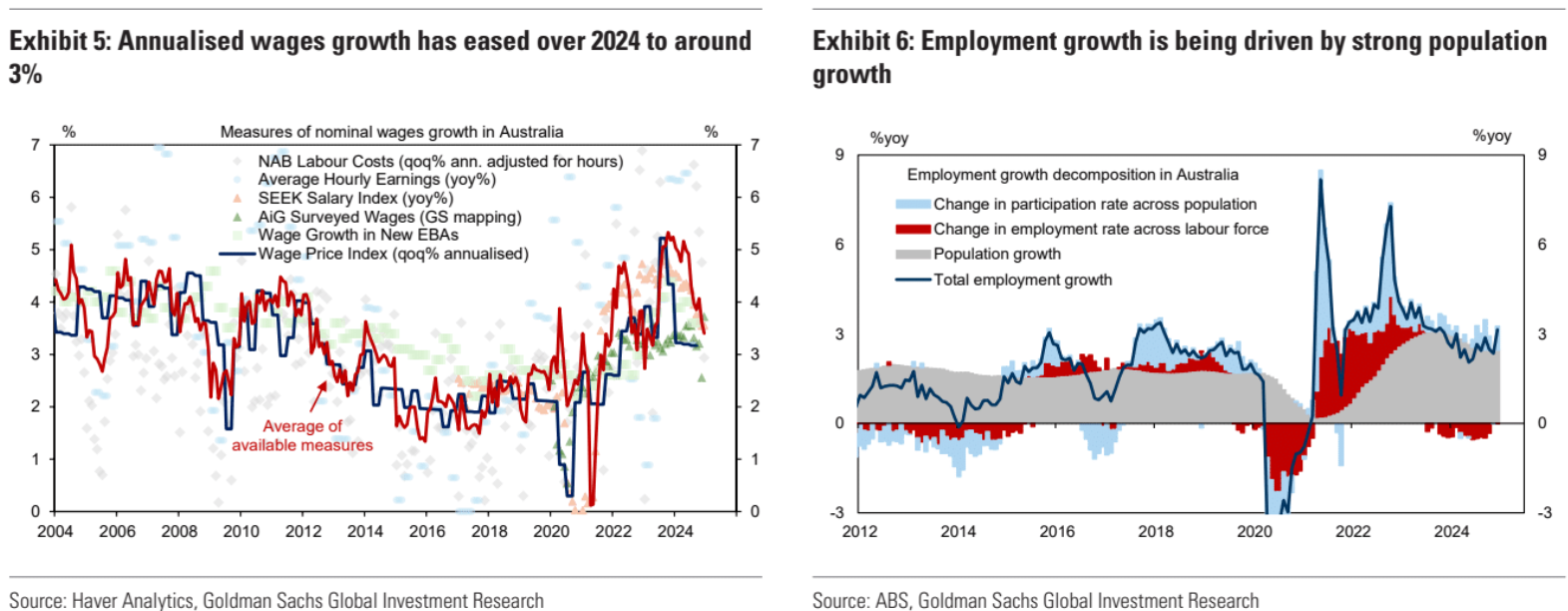

Looking at the labour market, some indicators like employment growth, labour force participation and job vacancies do remain strong and appear to work against the case for easier monetary policy – however, our analysis highlights three reasons why these measures are overstating the current strength of labour market conditions and reconcile with the observed sharp deceleration in wages growth (Exhibit 5) and inflation.

First, the post-pandemic immigration surge boosted labour supply, and this increased overall employment but put downward pressure on wages growth (Exhibit 6).

Second, Australia’s unique wage-setting mechanisms limits the ability of many workers to bargain for higher nominal wages in response to surging global inflation, resulting in an increase in labour market churn and the stock of unfilled vacancies – while simultaneously reducing the usefulness of job vacancies as an indicator of labour demand and wages growth (Exhibit 7).

And third, we estimate that around 40% of the 500k ‘social assistance’ jobs created in connection with the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) reflect an ‘informal to formal’ employment measurement issue rather than an actual increase in labour activity (Exhibit 8).

In view of these three caveats, we put more weight on other indicators pointing to a softening in labour market conditions in Australia, consistent with the signal from weak GDP growth and easing inflation pressures.

It is the immigration-led, labour force expansion economic model, and it does not do wage growth. Nor, therefore, inflation.

The evil RBA is paid to keep it a secret.