“Voluntary attendance. Online classes. Student numbers swelling”. The Guardian’s education correspondent, Caitlin Cassidy, has questioned the erosion of teaching standards at Australia’s universities, which have transformed into little more than “degree factories”:

More than a dozen academics who spoke to Guardian Australia on the condition of anonymity say their work has become undervalued and underpaid, with recycled, pre-recorded lectures and Zoom tutorials without attendance requirements leading to a steady decline in the value of tertiary education…

Several academics say their role is no longer about fostering learning, it’s about money – which means catering to the masses at as low a cost as possible.

“Universities are simply degree factories now,” a casual academic with 20 years experience in the sector says. “There is no focus on learning – academics aren’t encouraged to help people to learn”…

A sessional academic at a Victorian university says the learning standard has become “below average”, with course materials and case studies often “older than the students” themselves.

“Slides are rarely updated,” she says. “Lectures are mostly recorded and recycled each semester. Hardly any of the students listen to them and the tutors then have to do the lecturing as well, so a somewhat meaningful discussion can take place in class”…

“It was a trend happening before Covid but Covid gave it a huge injection. Numbers [of students] have increased so much, for many, it’s not a personal experience any more, it’s transactional”, [said professor of higher education at the University of Melbourne, Chi Baik].

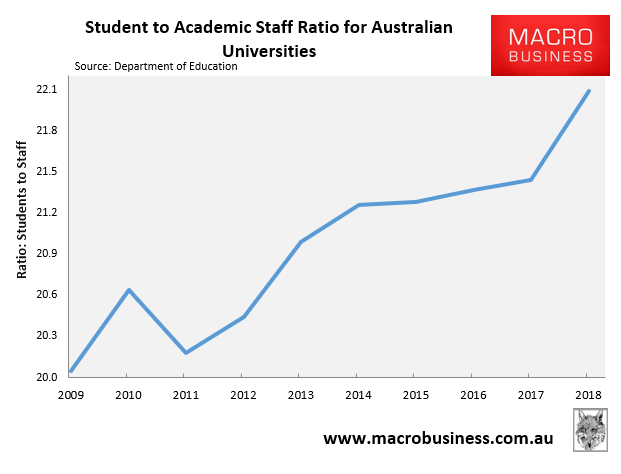

(In 1990 tertiary institutions had, on average, one staff member for every 14 students. In 2023, the figure was 22.)

“It’s always going to be challenging when there’s so many students to staff. You’re one in thousands”…

One academic who has worked at three Victorian universities says the standard of work has “never been so low”. It has reached the point he is considering moving to the private sector.

“I have been repeatedly asked to un-fail students,” he says. “People are graduating with little knowledge or applicable skills”.

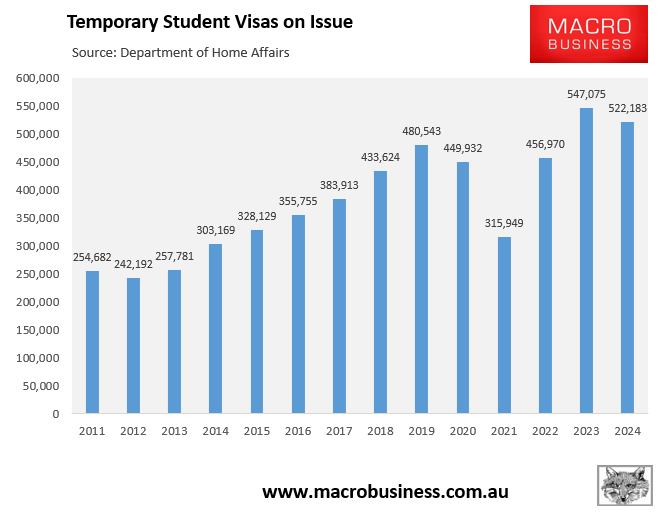

The erosion of pedagogical standards at Australian universities coincides with the unprecedented rise in international students.

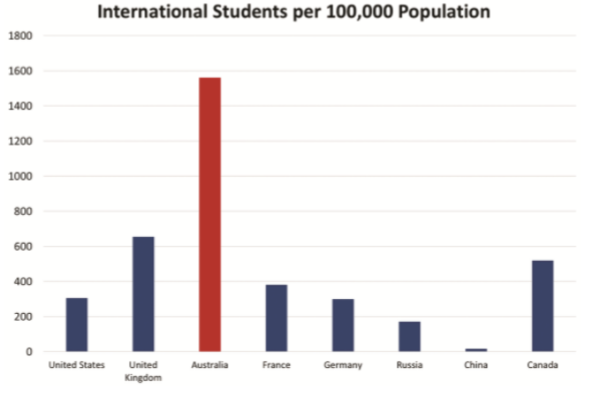

Before the pandemic, Australian universities had easily the highest concentration of international students in the world. This concentration has increased even more since.

Source: Salvatore Babones (2019)

The surge in student visas has coincided with an increase in the ratio of students relative to teachinng staff.

University teaching staff have been prohibited from failing international students because it would undermine their high-volume business model:

Local students have been forced to carry internationals through their courses via group assignments and cheating by international students is rife:

Some tutorials at Australian universities have even been conducted in foreign languages:

Policymakers colluded with universities to create a system that rewards university executives with fat salaries for transforming their universities into low-quality, high-volume migration mills.

- The Australian government offered generous student visa work rights and prospects for permanent residency.

- Australian institutions lowered entry and teaching standards.

The cash bonanza from the increased international student numbers was spent on research aimed at driving Australian universities up the world rankings rather than into areas that benefited Australians.

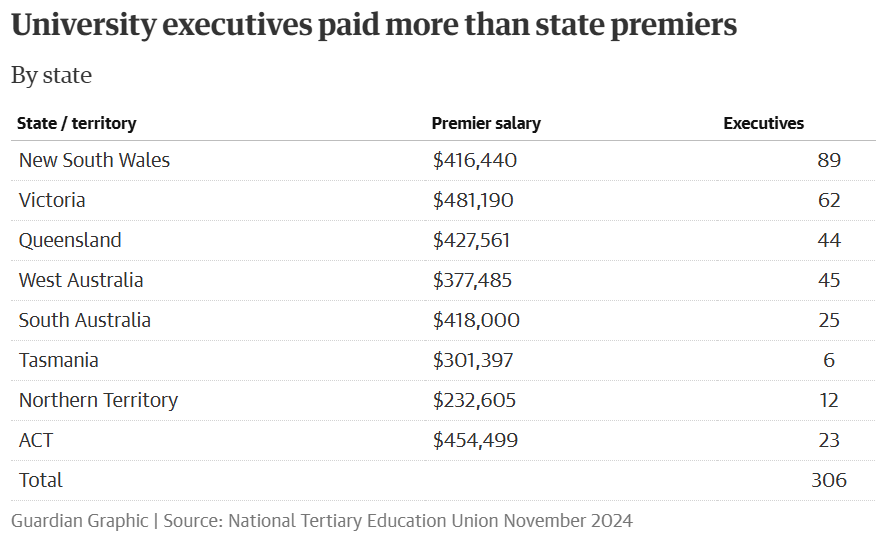

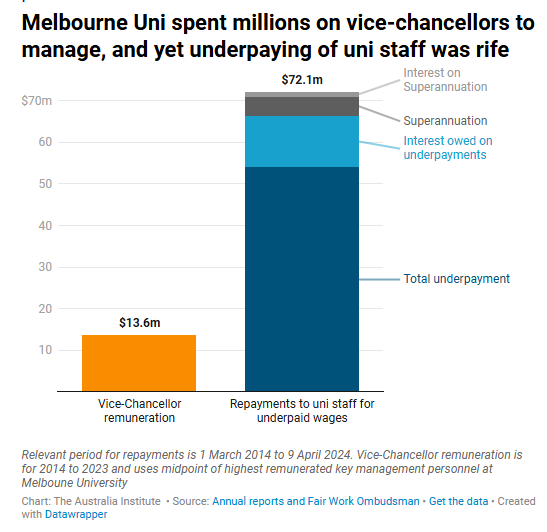

It also delivered gigantic salaries to university vice-chancellors and senior executives who earn more than state premiers.

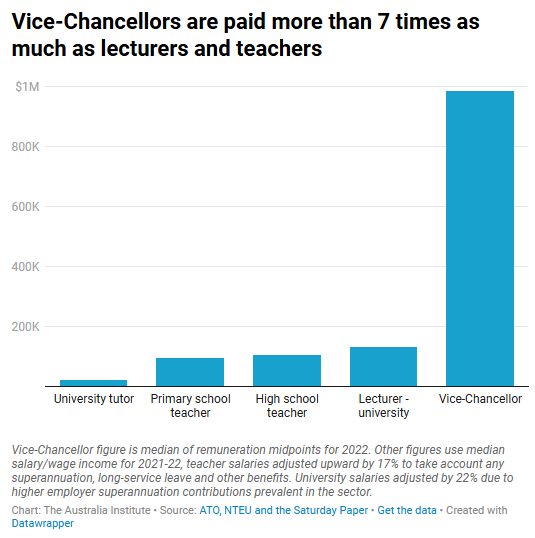

Australian vice-chancellor salaries in Australia are the highest in the world and tower over other education professionals.

According to a recent NTEU investigation of 545 council positions at 37 institutions, members from the Big Four accounting firms and industry groups hold up to half of the roles, with some university councils having more finance or mining executives than current academic practitioners.

The rise of large corporate appointments on university boards and executive pay coincided with increased precarious work, wage theft, and poor governance.

Put simply, vested interests have corrupted higher education in Australia.

Australia’s best interests were never served by running low-quality student visa mills.

Policymakers should instead aim to recruit a significantly smaller number of excellent (genuine) students.

This pivot to quality over quantity could be achieved with the following types of reforms:

- Significantly increasing English-language standards and requiring prospective students to complete entrance examinations before being permitted to study in Australia.

- Significantly increasing financial requirements, including requiring funds to be paid into an escrow account before arriving in Australia.

- Reducing the number of hours that international students are allowed to work and severing the direct link between study, work, and permanent residency.

- Allowing only top-of-class graduates to receive graduate visas.

- Because Australian universities are non-profit enterprises that do not pay taxes, imposing a levy on international students to ensure that Australians receive a financial return.

Australia’s universities should also be required to provide on-campus accommodation for international students in proportion to the number of enrolments to reduce pressures on the private rental market.

In short, Australia’s universities have burned their social licence.

They must transform into institutions of excellence that prioritise quality over quantity.