The Productivity Commission (PC) released a research paper entitled Housing Construction Productivity: Can we Fix it?, which tells a story of decades of poor performance.

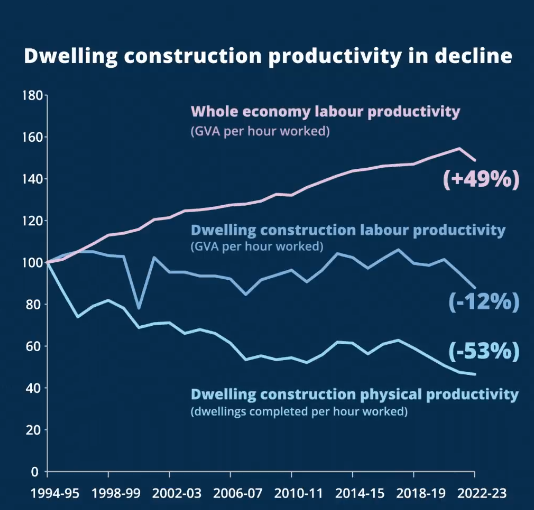

The PC found that building times for new homes have risen significantly in the last decade, and less than half (-53%) as many homes are being built per hour worked today compared to 30 years ago.

A more comprehensive productivity measure that controls for quality improvements and increases in the size of homes has declined by 12% over the same period.

Labour productivity in the broader economy increased by 49% over the same period.

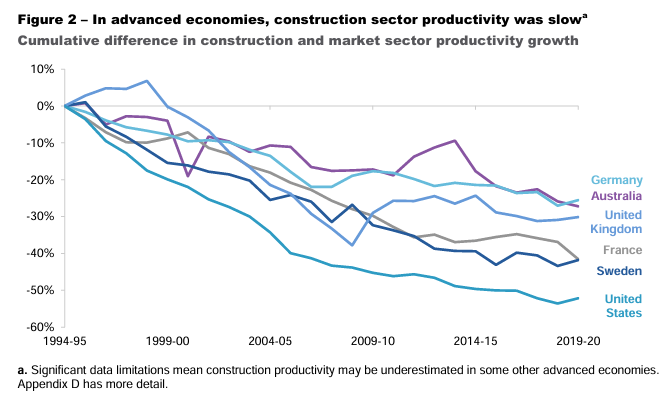

Similar declines in construction sector productivity have occurred across other advanced nations.

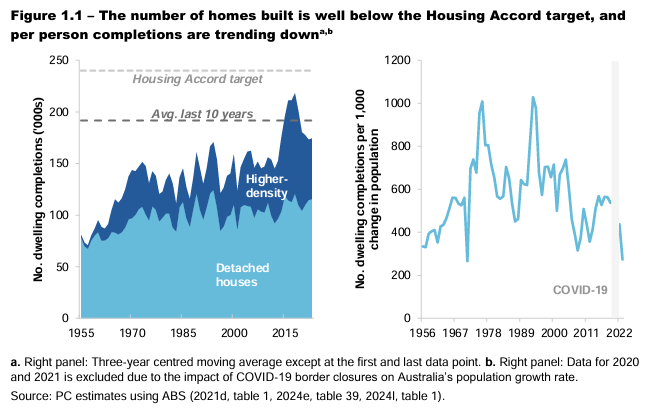

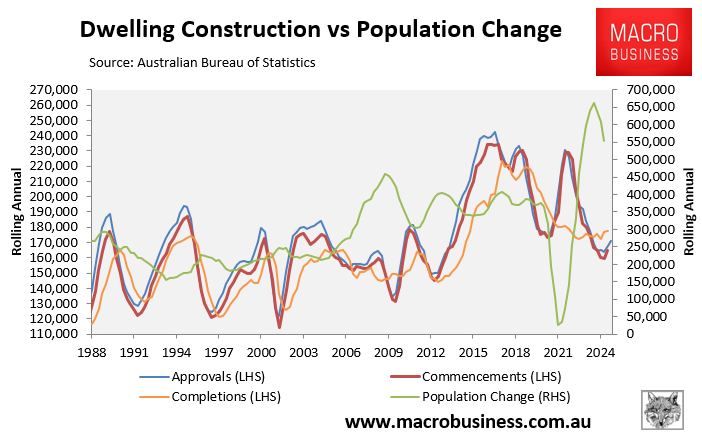

While the total number of new dwellings completed each year has roughly doubled since 1955, representing an annualised growth rate of 1.1% per year, relative to population growth, the number of housing completions has decreased for decades.

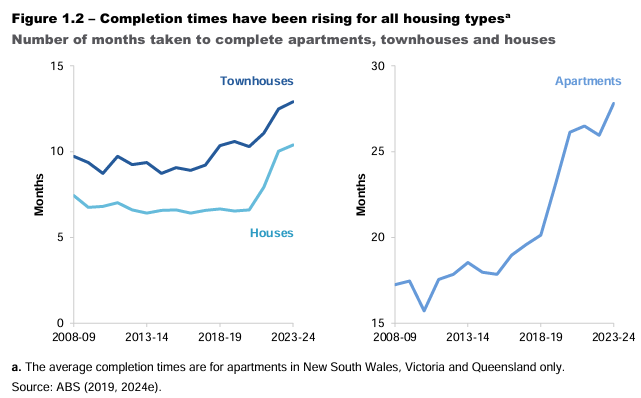

The average time to complete new housing has increased significantly in recent years.

In 2023-24, the average time to complete a single detached house was about 10.4 months, up from about 6.4 months a decade earlier. The average time to complete new townhouses rose from about 9.4 months to 12.9 months; for new apartments, it rose from about 18.5 months to 27.8 months.

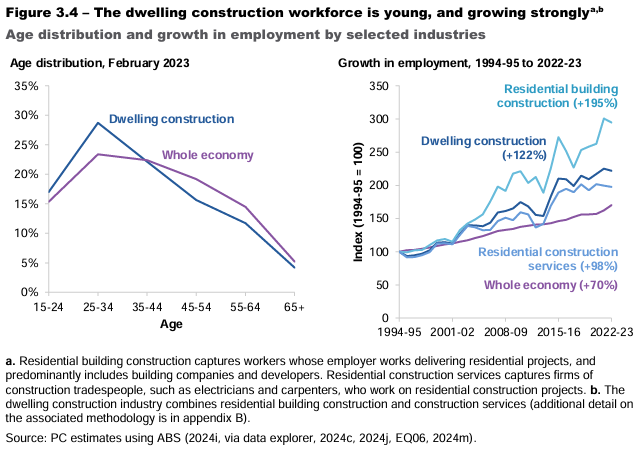

The PC notes that the construction workforce has grown strongly over recent decades compared to the broader economy. Moreover, despite frequent mentions of an ageing workforce, the construction workforce is also younger than the wider economy.

The PC contends that significant amounts of red tape are impacting new home construction, which is having a “deadening effect” on home building.

“Too many Australians, particularly younger Australians, are struggling to afford a home in which to live”, PC Chair Danielle Wood said.

“Governments are rightly focused on changing planning rules to boost the supply of new homes, but the speed and cost of new builds also matters”.

“Lifting the productivity of homebuilding will deliver more homes, regardless of what is happening with the workforce, interest rates or costs”, she said.

The PC calls for several reforms to help address the problem, including coordinated and streamlined regulation via an overhaul of the National Construction Code and a review of construction research and development to improve productivity.

Figure 3.4 above challenges the notion that a lack of construction workers is driving Australia’s housing shortage.

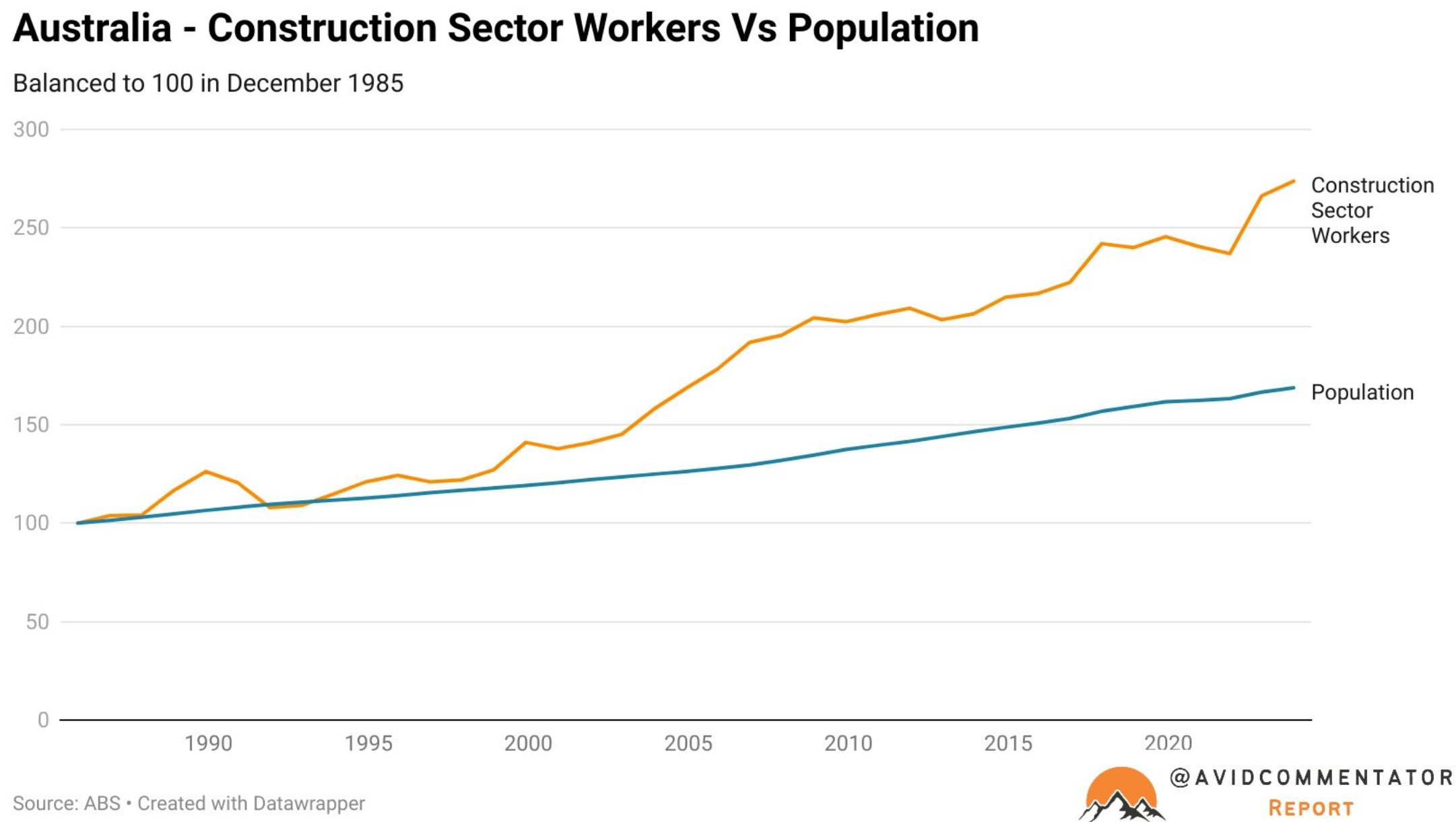

Independent economist Tarric Brooker likewise noted that “since 1994, the construction sector has expanded at a much faster rate than the population, with the sector growing by 126.3% compared with 49.6% for the broader population”.

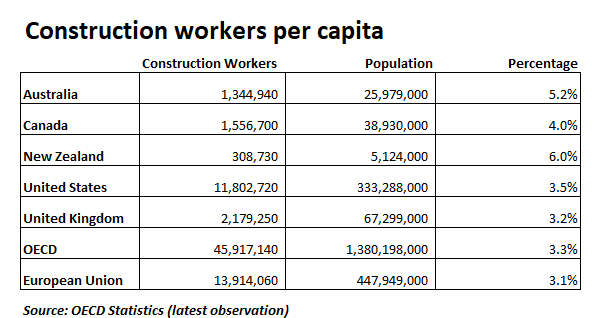

Australia also has one of the largest construction workforces in the world relative to its population:

So, what is happening here? Why has Australia’s construction employment grown so rapidly without a corresponding increase in residential construction?

Australia’s construction sector has been overrun by suits rather than tradies, resulting in a larger workforce and reduced production.

“The rapid rise in the number of professional workers that are now required to deliver projects across the country is at odds with the number of workers ‘on the tools’”, RLB’s Oceania director of research, Domenic Schiafone, noted in August.

“In 2003, professional workers accounted for 28% of the construction workforce. By 2023, this had risen to 38%.”

The AFR’s Michael Bleby observed that “the industry as a whole is suffering from an imbalance of too few workers on the ground and too many in the office”.

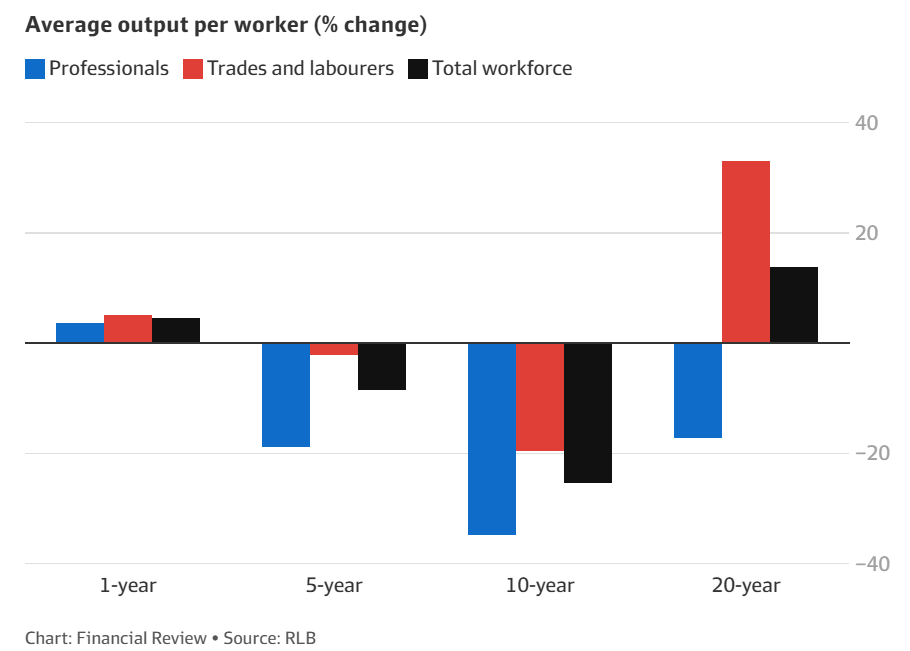

This largely explains the slump in productivity across the construction industry:

“The growth in professional employees – professionals with tertiary degrees and building technicians with advanced diplomas – surged, rising 125% over the two decades from 242,900 to 547,300”, Bleby wrote.

“But the annual output per professional worker fell 17.2% to $470,900 from $568,900”.

As a result of the increase in suits, Australia’s construction sector has an excess of workers in aggregate but insufficient front-line workers on the tools.

A comparable situation has occurred in numerous sectors of Australia’s economy, including public services, universities, and utilities.

Administrators in suits have taken over from front-line employees who deliver goods or services.