Australia’s last major plastics manufacturer, Qenos, closed last year due to high energy costs. Now, Australia is wholly reliant on imported plastics from China.

In February, Australia’s only architectural glass manufacturer, Oceania Glass, collapsed after 169 years of operation, amid soaring gas costs.

Oceania Glass was Australia’s only manufacturer of architectural flat glass, producing and distributing format glass for use in Australian homes and buildings.

According to the company’s website:

“We have a proud heritage serving Australia, having sold our very first glass in 1856 and are the only architectural glass-maker in Australasia”.

“Our glass is featured in many of Australia’s most iconic buildings, including the Australian Parliament House”.

Oceania Glass required large amounts of energy, particularly gas, to maintain the 2000-tonne furnace at the heart of its operations.

“Certainly, for us as glass manufacturers, there are no real current alternatives for glassmaking outside of natural gas or other carbon fuels”, Oceania Glass chief executive Corné Kritzinger stated in January 2022.

Oceania Glass officially shuttered on Monday 3 March, and CEO Corné Kritzinger left the following heartfelt message on LinkedIn:

On Monday, 3 March 2025, Australia lost another critical manufacturing capability—architectural float glass. The closure of the country’s last remaining float glass plant was a quiet event, attended only by employees. This stood in stark contrast to its grand opening 51 years ago, when political and business leaders gathered to celebrate a milestone in Australian manufacturing.

There was no media coverage, no public acknowledgment—most Australians remain unaware that an entire industry has disappeared from their own backyard.

For the past 11 years, Australia had just one operating float glass plant. Now, there are none. We are entirely dependent on imported glass.

The reasons behind this closure are complex, but they boil down to one fundamental issue: Australia’s economic and regulatory environment is increasingly unfavourable to manufacturing. The challenges were insurmountable.

This business had a long and proud history. It began in 1856, importing glass into Victoria. In 1931, the first manufacturing plant opened in Sydney, producing patterned glass and shortly thereafter sheet glass. A drawn sheet plant- the predecessor to float glass – commenced in Dandenong, Victoria in 1962. Then, in 1974, Australia’s first float glass line, and the first in the Southern Hemisphere, was established in Dandenong. This investment drove rapid growth, leading to a second float line in Ingleburn, Sydney, in 1988 during Australia’s Bicentenary.

Float glass production is both an art and a science. It requires precisely blending seven raw materials and melting them in a furnace at a staggering 1600°C—comparable to the belly of a dragon.

Natural gas fuels this intense heat, triggering complex chemical reactions that transform raw ingredients into perfectly smooth, crystal-clear glass.

But now, that dragon’s fire has been extinguished—permanently.

To all who have worked for and alongside this business over the past 169 years, thank you. Your contributions and dedication have shaped an industry that, though gone from our shores, will not be forgotten.

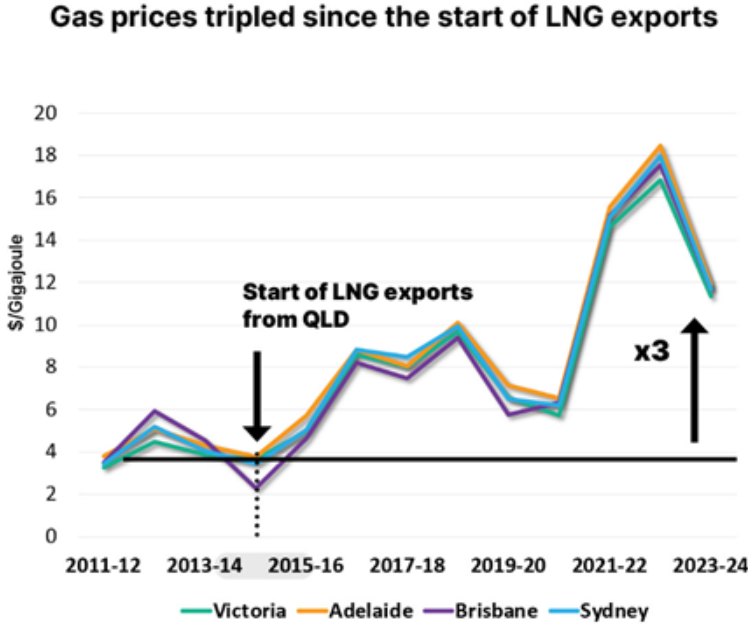

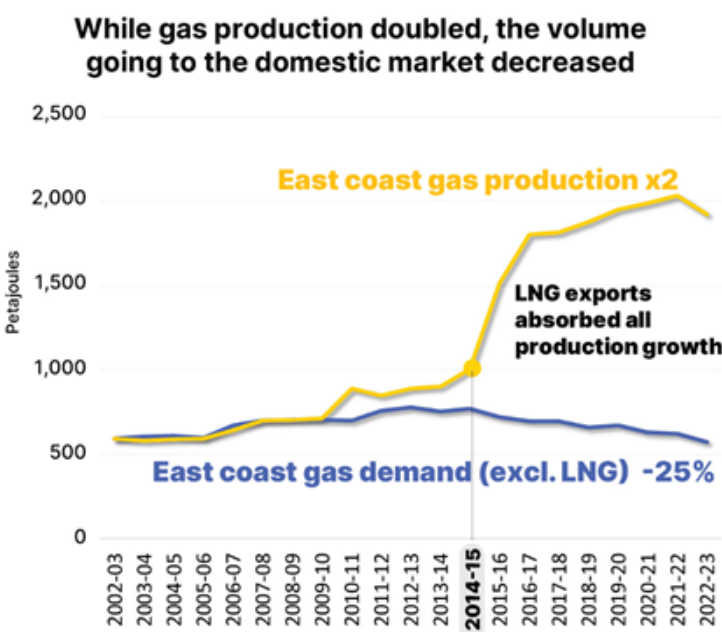

Obviously, the hyperinflation of East Coast gas costs made Oceania Glass unviable.

These costs are certain to soar even higher once LNG import terminals are built in NSW, Victoria, and South Australia, thereby locking in import parity prices at the same time as nearly three-quarters of East Coast gas is exported, mostly to China.

So, while Australia exports most of its East Coast gas to China, it will now import plastics, glass, and nearly every other manufactured good from China, thanks to expensive energy costs.

All of Labor’s fantastical 1.2 million housing construction target will now rely on imported windows.

We are not a serious country.