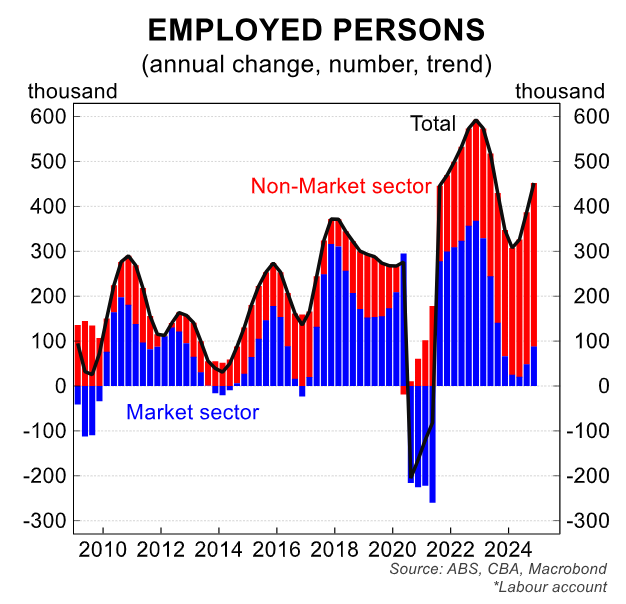

Harry Ottley, economist at CBA, published a terrific set of charts showing the explosion in non-market jobs, where there is often a lack of market prices and wages are heavily subsidised by the government, and the implications for Australia’s labour productivity.

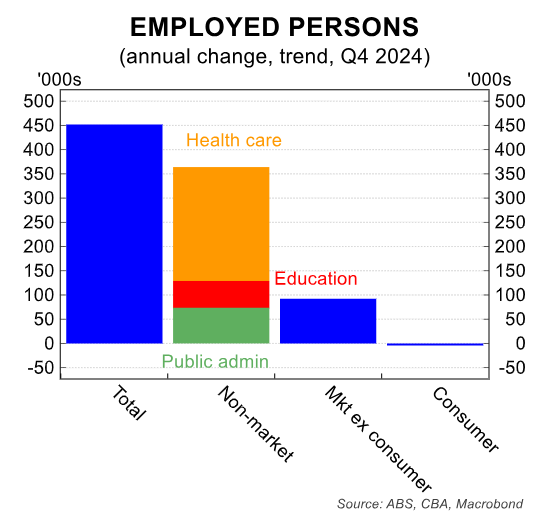

Ottley shows that in the year to Q4 2024, the number of employed persons in the non-market sector increased by 364,000 in trend terms, compared to only 88,000 in the market sector.

The growth within the non-market sector was driven by health employment, which grew by 235,000 annually. By contrast, employment in industries exposed to weak consumer spending was 4,000 lower.

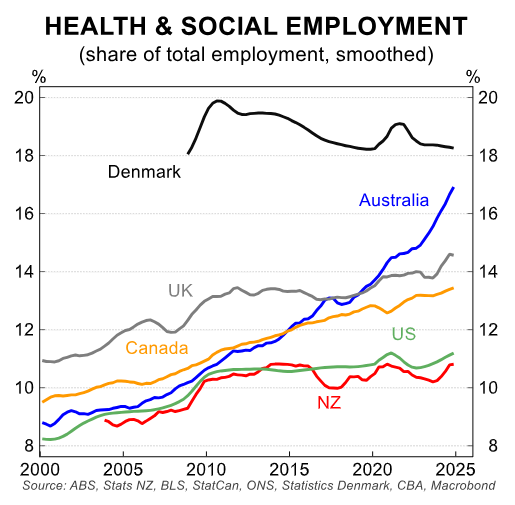

The following chart from Ottley shows the growth in Australia’s healthcare and social employment against other developed nations.

As you can see, the growth in healthcare and social employment has been significantly stronger than peer economies. This has taken Australia’s healthcare employment share well above other English-speaking economies.

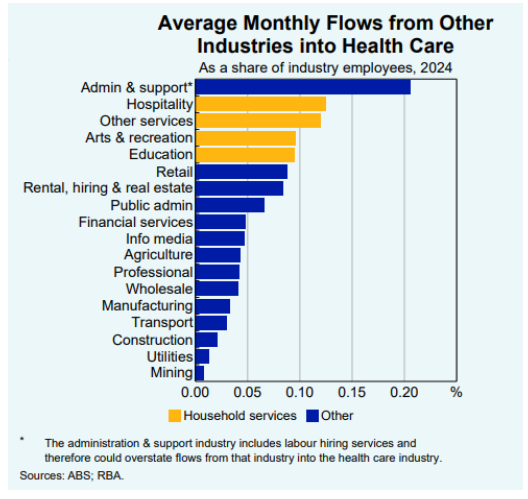

Ottley provided the following chart from the RBA showing how the growth in health sector employment has come from those not previously employed and from other industries.

Key industries that have lost employment to healthcare include hospitality, other services, recreation, and education.

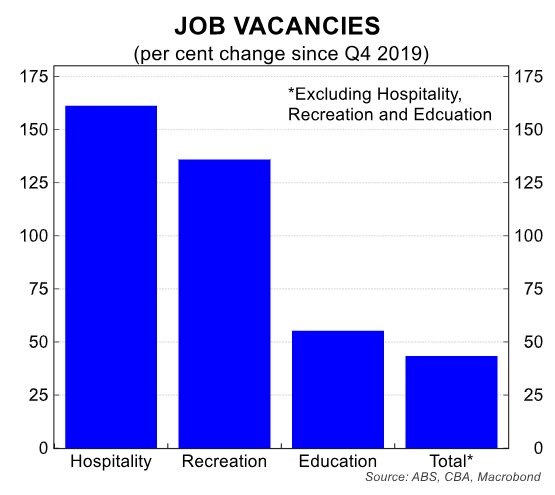

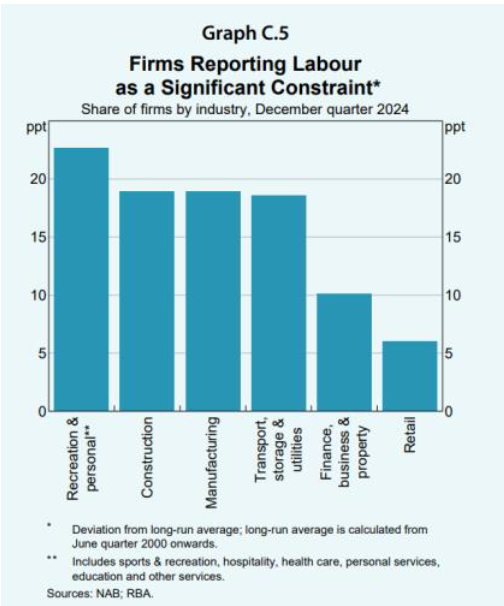

This flow of workers into healthcare and social assistance has driven up job vacancies in hospitality, recreation, and education.

As a result, the NAB business survey has reported labour shortages in these sectors.

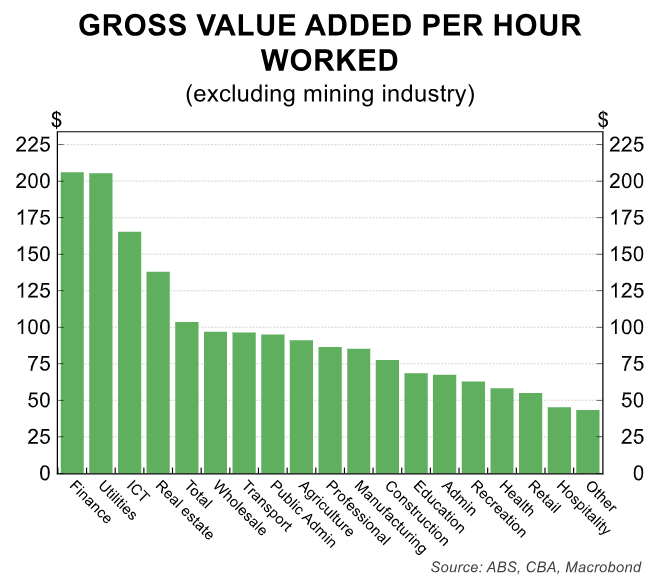

One upside is that the sectors that have lost workers to healthcare and social assistance also have low labour productivity.

“This cushions the productivity impact of the compositional shift in the workforce compared to if workers were coming from more highly productive industries”, noted Ottley.

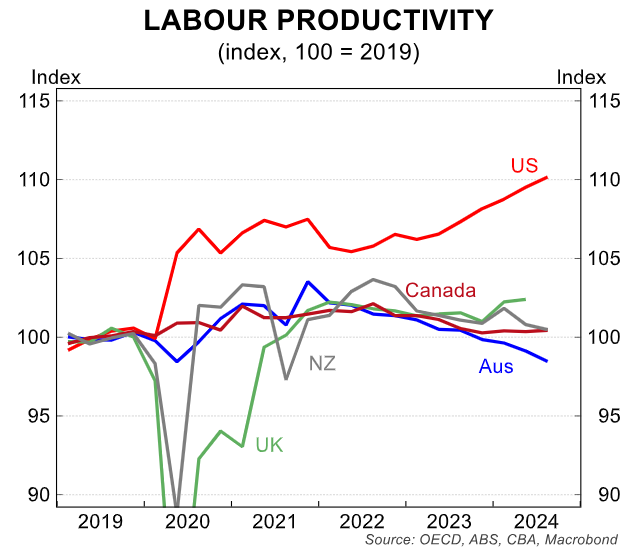

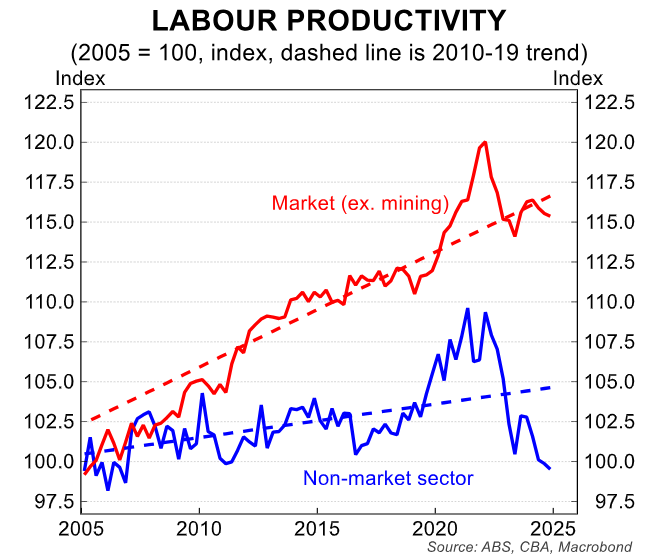

Even so, Australia’s productivity growth has been especially poor, as illustrated by Ottley below.

“Labour productivity growth is especially soft in the non-market sector which is growing as a share of the economy”, noted Ottley.

“This is creating a dual drag on overall measured productivity through the compositional shifts and weak/negative outright growth in productivity within the non-market sector”.

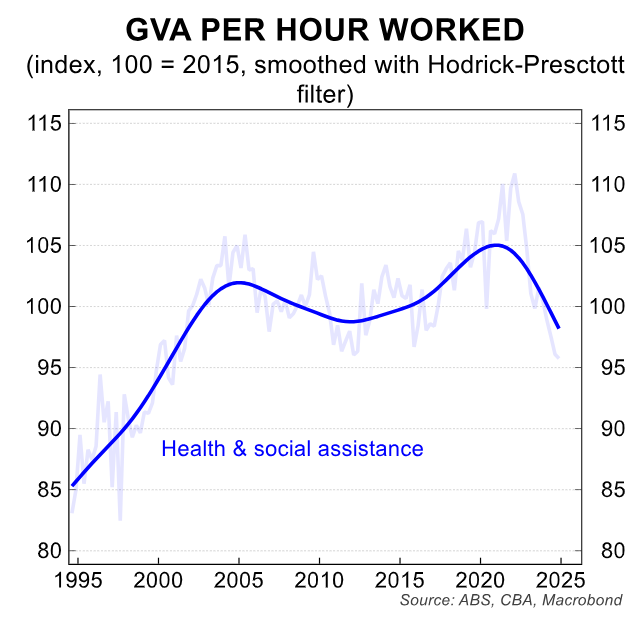

Indeed, the recent weakness within the non-market sector has been driven primarily by the huge surge in health & social assistance jobs, mostly driven by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The final chart from Ottley shows that the current gross value added (GVA) per hour worked in the healthcare and social assistance industry is the same as at the turn of the century.

However, Ottley cautions that it is “plausible that difficulty in measuring output in the industry means production is underestimated”.

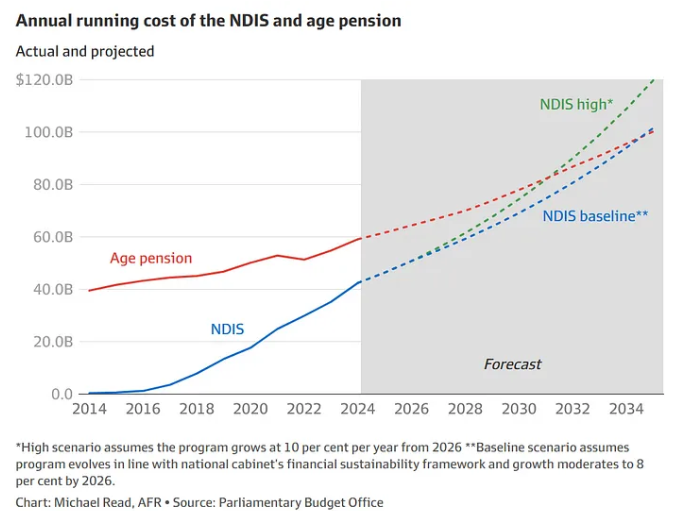

It is difficult to see how Australia’s labour productivity will rebound given the NDIS is projected to expand aggressively, driving growth in non-market jobs.

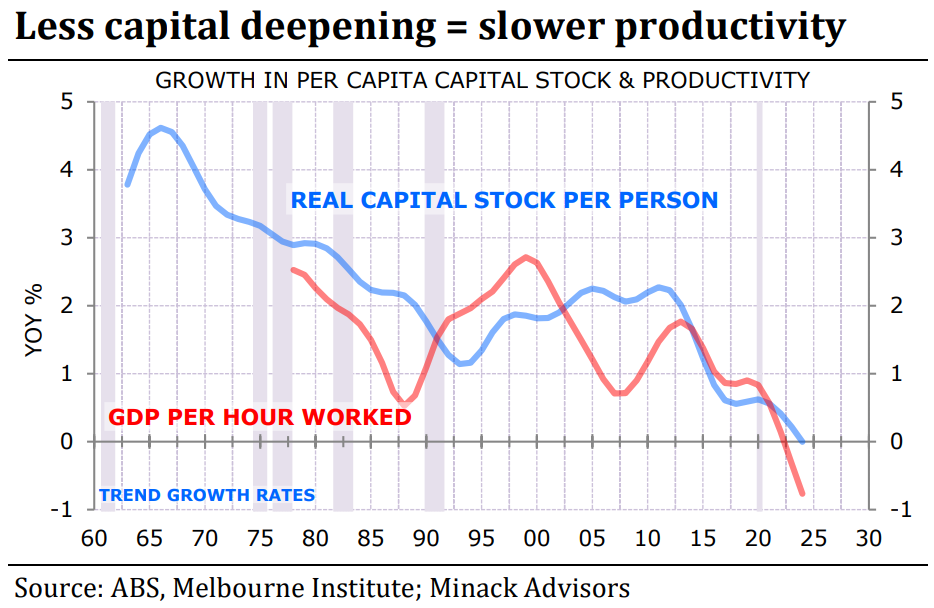

Australia’s capital stock will also continue to shallow if the population via immigration continues to increase at a faster pace than business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

As explained this month by the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) Michael Plumb:

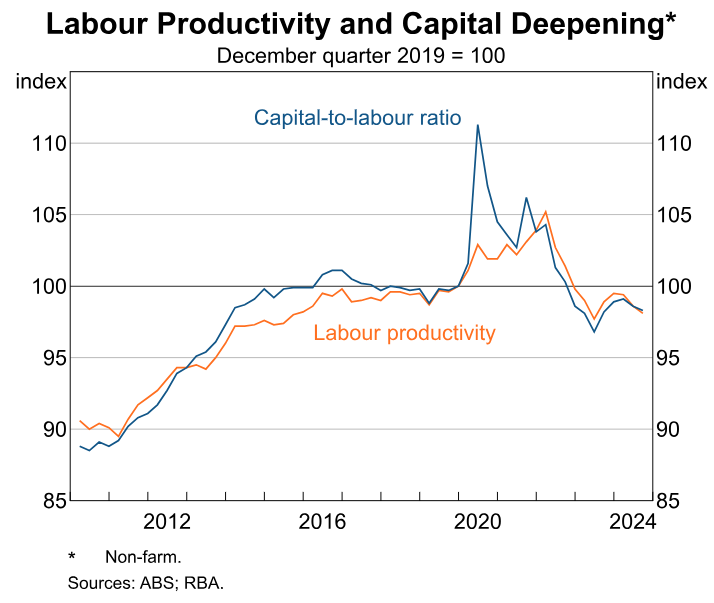

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”…

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy – or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”.

“Capital per worker was broadly unchanged for around five years leading up to the pandemic and – looking through the volatility in the data during the pandemic – is currently a bit below those levels”.

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong growth in employment”.

Ross Gittins explicitly singled out persistently high immigration as a significant cause of Australia’s declining productivity:

“If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up”.

“In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening”.

“Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states”.

If Australia’s productivity growth does not improve, living standards will stagnate.