Former Treasury Secretary Dr Martin Parkinson, who led the federal government’s 2023 Migration Review, admitted that Australia’s mass immigration policy has failed to provide the nation with the skills it needs and has contributed to poor productivity growth.

As part of a campaign entitled Activate Australia’s Skills, Dr Parkinson called for a nationally cohesive approach to skills assessment to address workforce shortages.

“One in three occupations has skill shortages, and yet half of our permanent migrants are working jobs that require a skill level less than what they actually have”, he said.

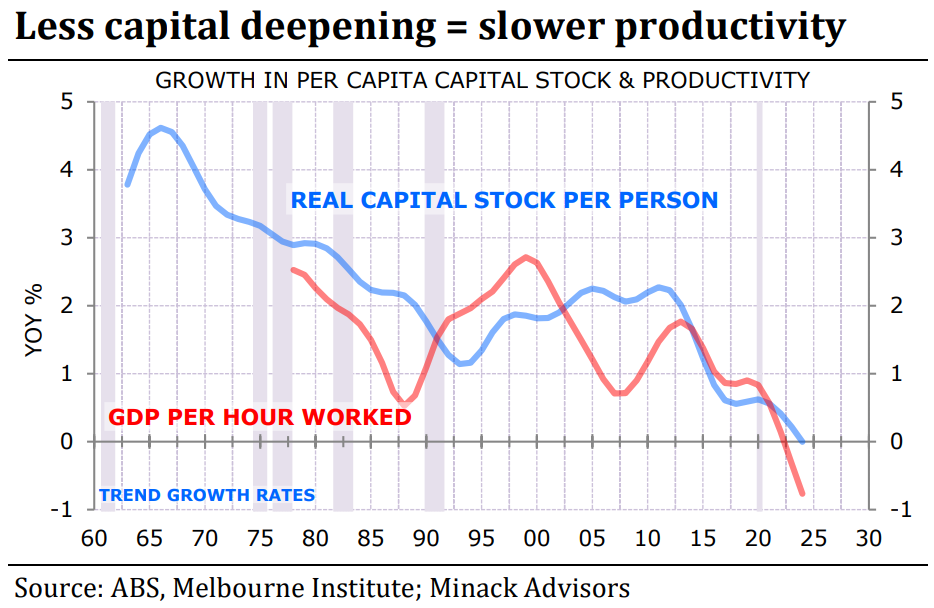

“It contributes to slower productivity growth in Australia, and it makes it harder for those migrants to actually contribute to the maximum extent possible”.

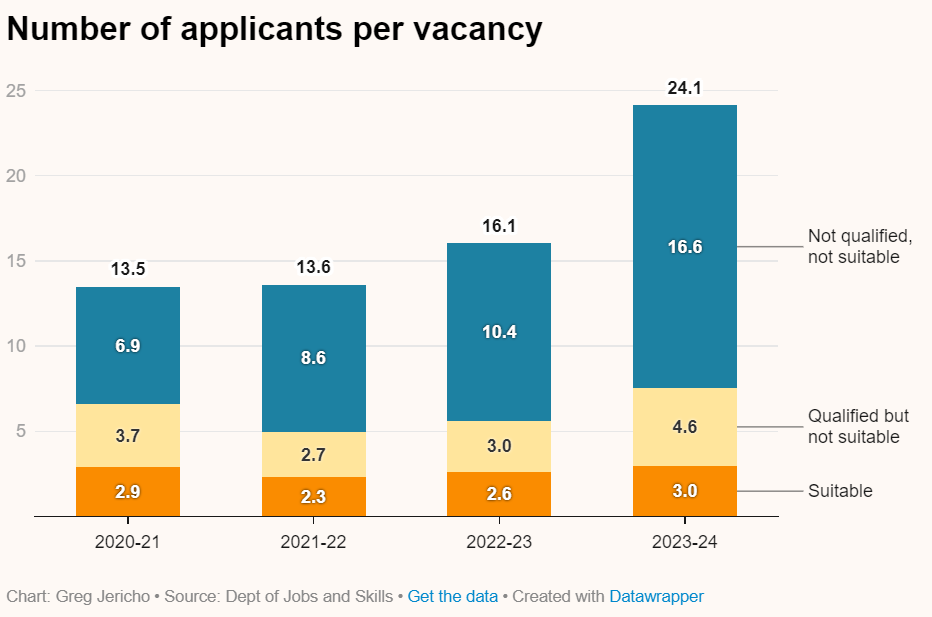

As shown recently by Greg Jericho, Australia’s reported labour shortages came in spite of “a lot more people applying for each job”. The problem was a severe lack of “qualified and suitable candidates applying for jobs”.

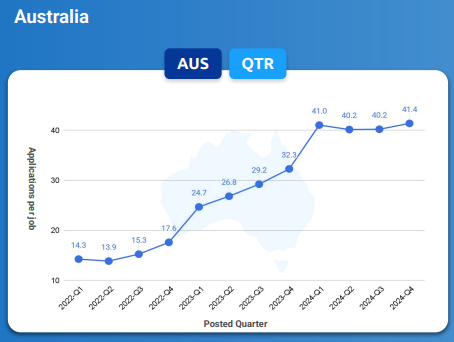

JobAdder’s latest report backed this view, showing that the number of job applications surged 47% in 2024, with the average job in Australia attracting a series-high 41 applicants

Source: JobAdder

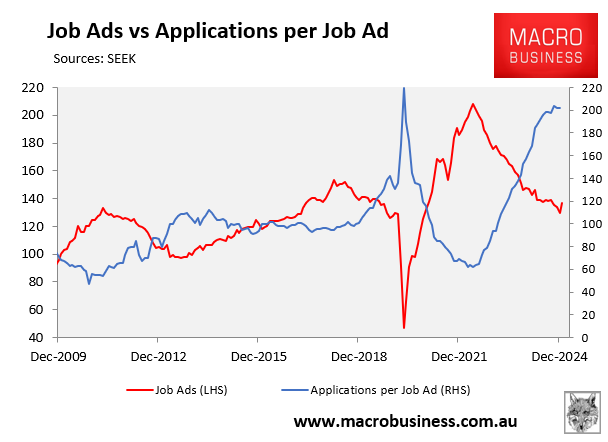

SEEK’s latest employment report also showed a significant increase in applications per job ad.

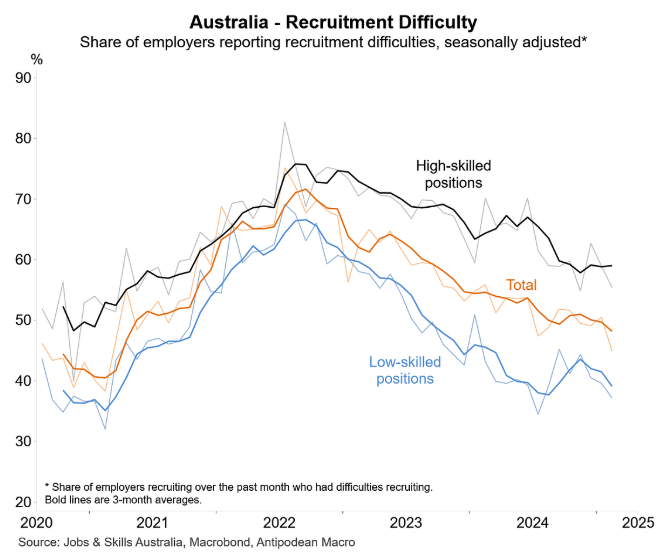

The latest data from Jobs & Skills Australia, collated by Justin Fabo of Antipodean Macro, showed that employers have little difficulty filling low-skilled jobs but continue to struggle to fill high-skilled positions.

The reality is that a significant percentage of Australia’s purportedly ‘skilled migrants’ work in low-skilled jobs unrelated to their qualifications.

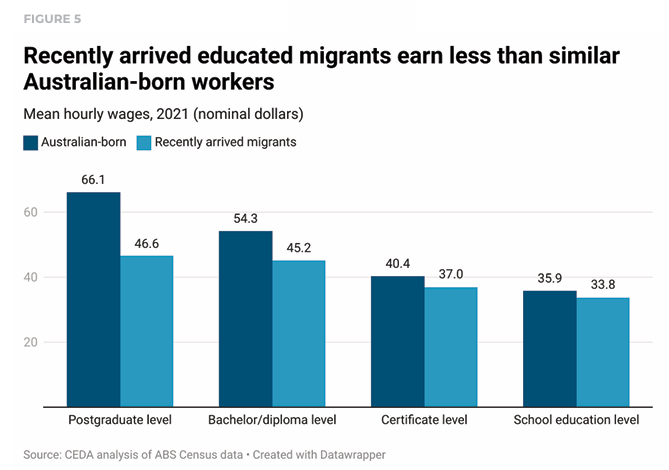

The Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) examined the most recent census, revealing that Australia’s ‘skilled’ migrants are chronically underemployed and underpaid.

“Recent migrants earn significantly less than Australian-born workers, and this has worsened over time”, CEDA senior economist Andrew Barker said.

“Many still work in jobs beneath their skill level, despite often having been selected precisely for the experience and knowledge they bring”.

The CEDA analysis highlighted that Australia’s migration system was likely contributing to the nation’s chronically poor productivity growth.

“Labour productivity and wages are closely linked, indicating that migrant labour is not being used as productively as it could be”, the report said.

“This decade, migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”.

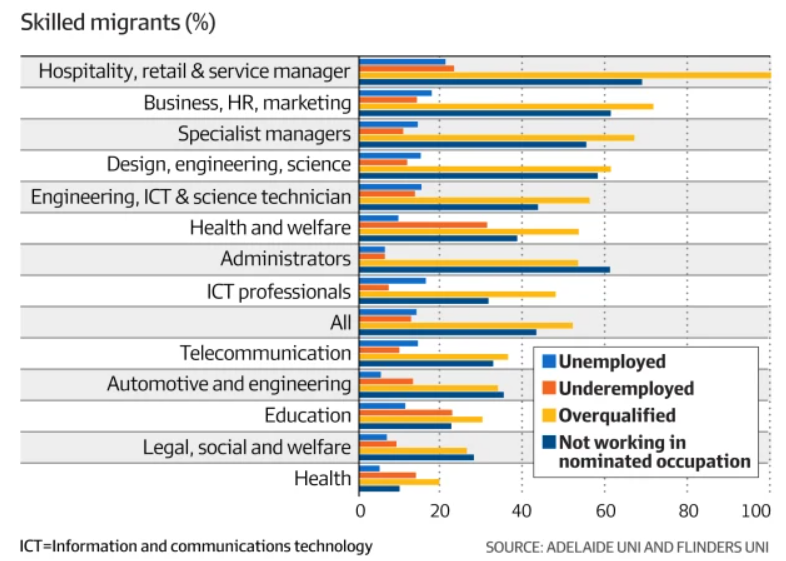

Adelaide University’s George Tan estimated that 43% of skilled migrants who exploited the state-sponsored visa system were not working in their stated occupation.

Most skilled migrants worked in low-productivity areas like retail, hospitality, and service management and were overqualified.

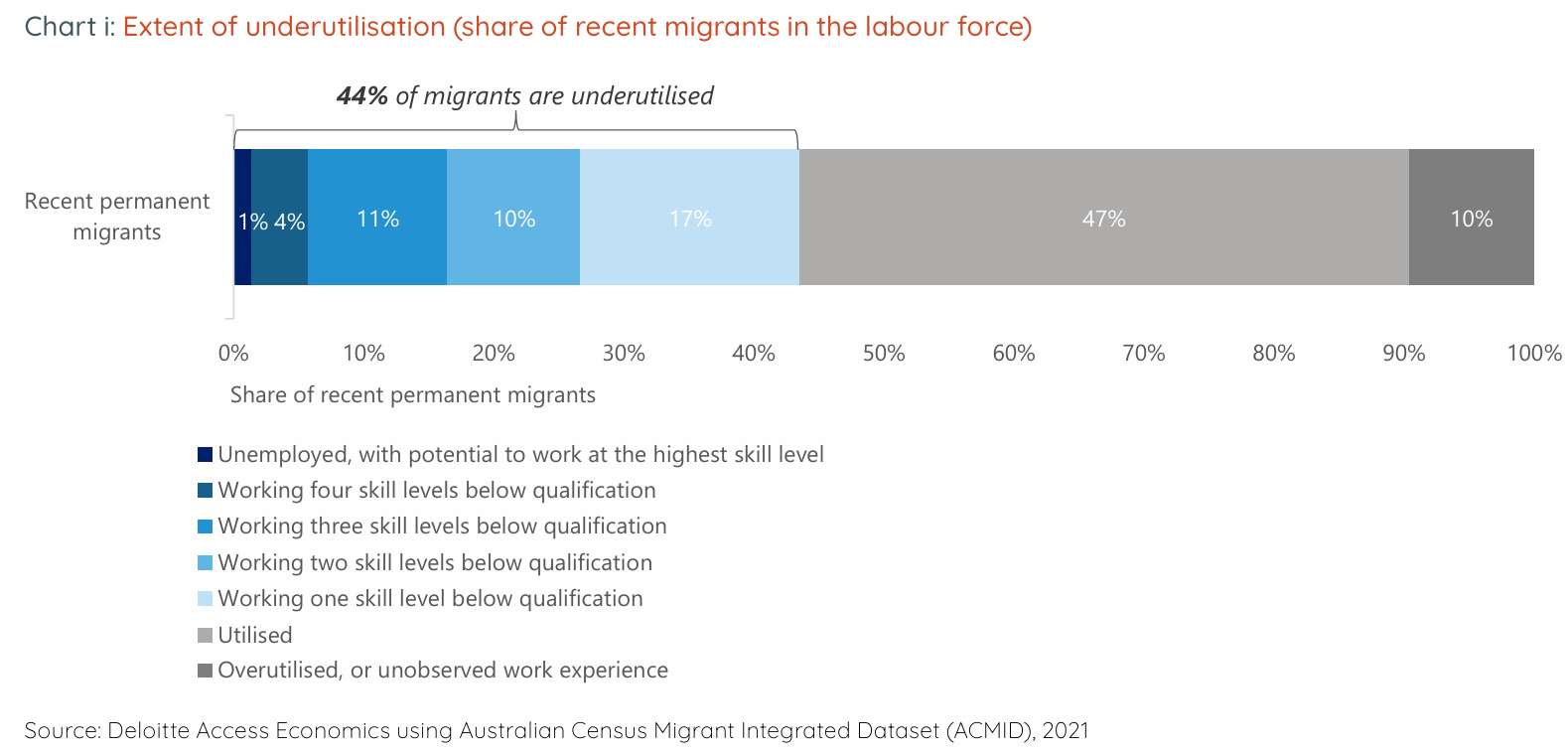

Deloitte Access Economics uncovered that 44% of permanent migrants in Australia were working in jobs below their skill level in 2023. The majority of these underemployed migrants entered through the skilled stream.

Deloitte projected that over 620,000 permanent migrants work below their skill levels and credentials. Of these, almost 60%, or 372,000, entered the skilled migration system.

On average, among those permanent migrants who arrived in Australia in the last 15 years, almost half (44%) are working in an occupation at a lower-skill level than is commensurate with their qualifications (Chart 1).

This means in 2024, there are more than 621,000 permanent migrants living in Australia who are underutilised and not working to their full potential.

Despite the permanent migration program’s focus on attracting overseas qualified professionals with skills in demand that address labour shortages, almost six in ten underutilised permanent migrants in Australia entered via the skills stream.

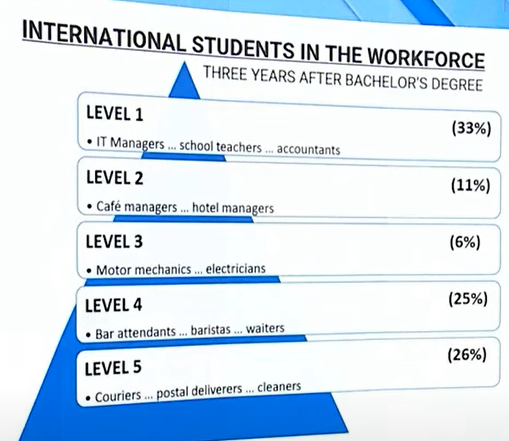

The federal government’s own Migration Review, led by Dr Parkinson in 2023, found that 51% of overseas-born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees worked in unskilled employment three years after graduating.

Source: Migration Review (2023)

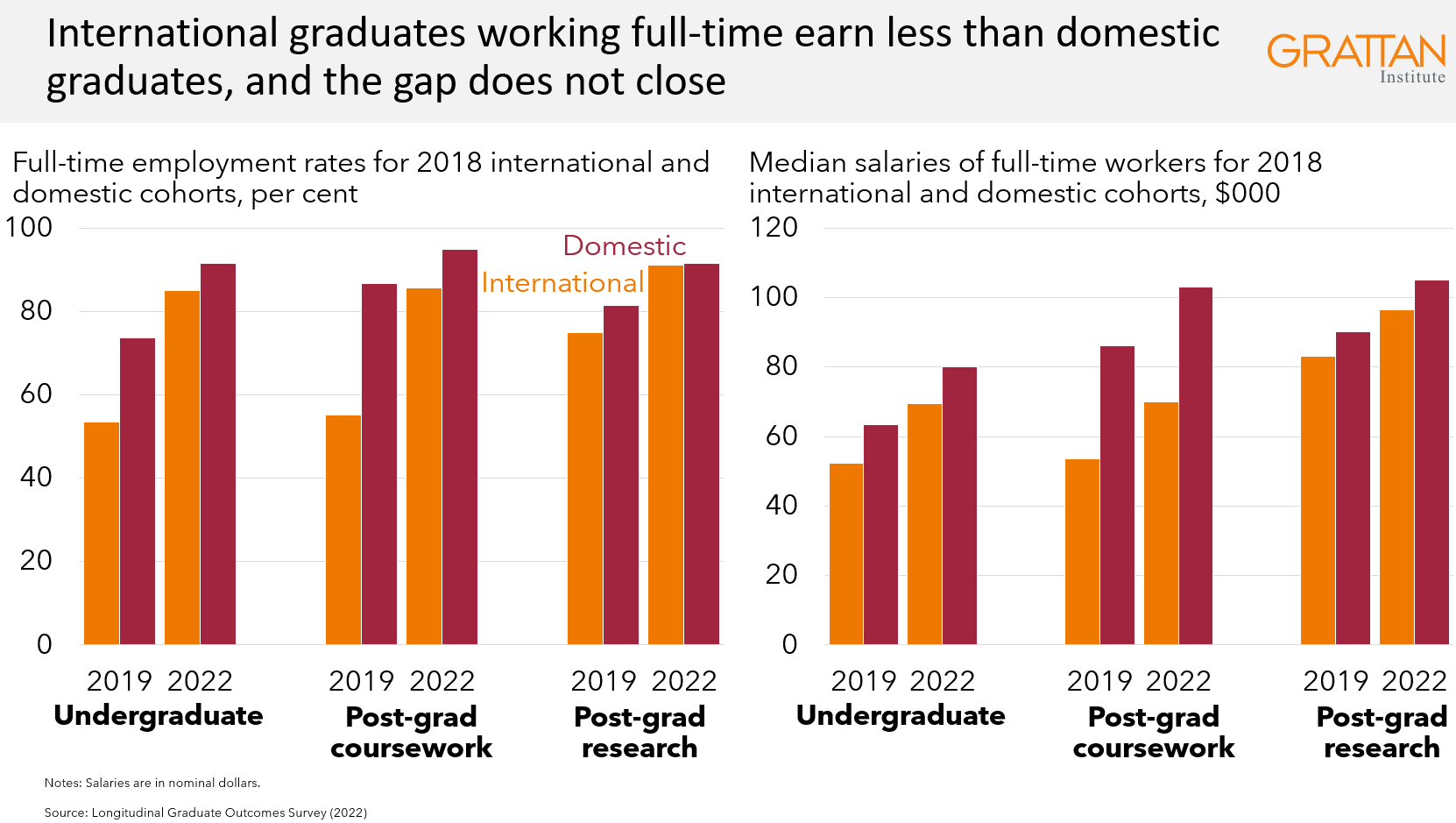

Finally, the Graduate Outcome Survey regularly reports that student graduates earned significantly less than locally born graduates and experienced worse labour market outcomes.

Mass immigration has, therefore, failed to provide Australia with the necessary skills, resulting in ongoing infrastructure and housing shortages, as well as environmental degradation.

It has also thinned out the nation’s capital base, contributing to the decline in labour productivity.

Sadly, you will never see shills like Martin Parkinson arguing for lower immigration given his role as Chancellor of Macquarie University. Instead, he says asinine things like:

“It’s not about the size of the migration program, irrespective of whether you want a small migration program or a large program”.

“It’s about making sure whomever we bring in here actually gets to contribute to their fullest potential”.

The reality is that quality and quantity matter.

A large migration program negatively impacts housing, infrastructure, water supplies, the natural environment, and broader living standards.

The optimal policy is running a smaller, more skilled, well-paid migration system.

The wage floor for all skilled visas should be higher than the median full-time salary (now around $90,000). All skilled visas should also be employer-sponsored, allowing qualified migrants to begin working in their field of competence immediately.

All types of retirement visas, including parental and ‘golden’ tickets, should be abolished.

Australia’s migration system is failing. Australia deprives poor countries of talent while exacerbating domestic skills, housing, and infrastructure shortages and thinning the nation’s capital base.