Last week, I critiqued an interview with former immigration department bureaucrat turned influencer, Abul Rizvi, on Joseph Walker’s podcast.

In the interview, Rizvi explicitly admitted that slowing population ageing comprised about “80%” of the motivation for massively increasing Australia’s intake of migrants in the early 2000s.

Until spending about a week reading up on Aus immigration policy and then interviewing Abul Rizvi (a former Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration) in late Jan, I hadn’t realised that probably the dominant rationale of Aus immigration policy over the past couple of… pic.twitter.com/ybU9Vh9KCi

— Joseph Noel Walker (@JosephNWalker) February 17, 2025

I countered this claim with decades of research from the Productivity Commission (PC) debunking the myth that immigration is a countermeasure to population ageing. For example:

- PC (2005): “Despite popular thinking to the contrary, immigration policy is also not a feasible countermeasure [to an ageing population]. It affects population numbers more than the age structure”.

- PC (2010): “Realistic changes in migration levels also make little difference to the age structure of the population in the future, with any effect being temporary“…

- PC (2011): “…substantial increases in the level of net overseas migration would have only modest effects on population ageing and the impacts would be temporary, since immigrants themselves age… It follows that, rather than seeking to mitigate the ageing of the population, policy should seek to influence the potential economic and other impacts”…

- PC (2016): “[Immigration] delays rather than eliminates population ageing. In the long term, underlying trends in life expectancy mean that permanent immigrants (as they age) will themselves add to the proportion of the population aged 65 and over”.

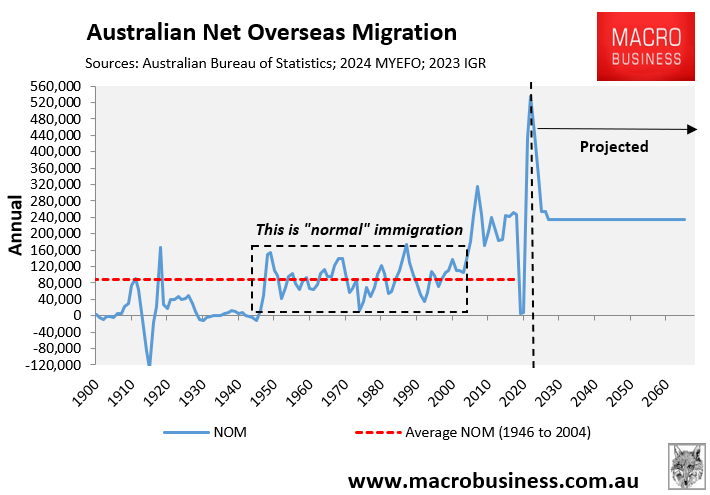

I also cited old research from demographer Peter McDonald, who Rizvi claims is Australia’s leading demographer, stating that “it is demographic nonsense to believe that immigration can help to keep our population young”. McDonald also stated that “annual net migration above 80,000 become increasingly ineffective and inefficient in the retardation of ageing”.

The reasons should be obvious. Any demographic dividend from immigration can only be temporary since migrants also grow old. And when they do, they will add to the pool of elderly Australians in the future, thereby requiring an ever-larger intake of migrants to ameliorate population ageing and an ever-larger population—classic ponzi demography.

Australia is currently paying the price with respect to ageing from its post-war migration boom.

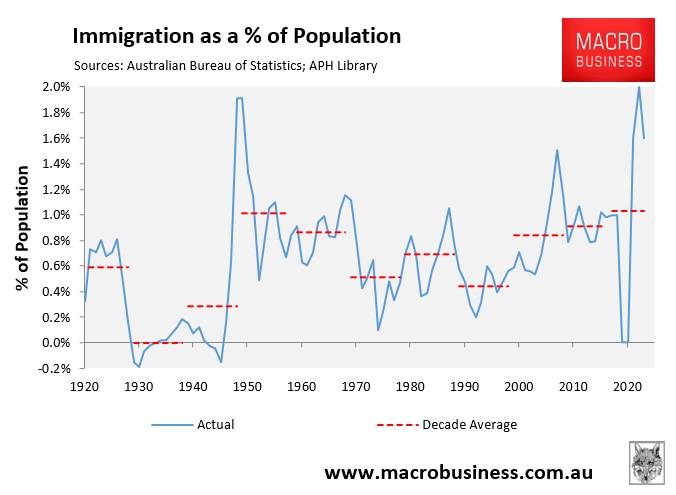

As illustrated in the following chart, a key driver of Australia’s ‘baby boomer bulge’ is the mass immigration program run in the post-war period (i.e., the 1950s and 1960s):

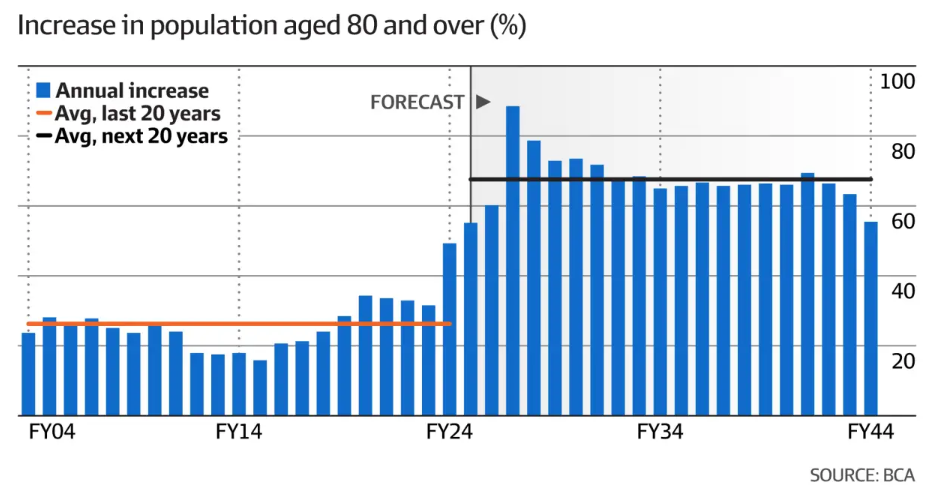

As reported in The AFR on Wednesday, Australia is now facing an “ageing time bomb” that will “overwhelm hospitals and budgets”:

“In just two years – in 2027 – about 80,000 baby boomers will turn 80, compared with an average of about 20,000 new octogenarians each year between 2000 and 2020”, The AFR’s John kehoe reported.

“The number of people turning 80 will hover around 60,000 for the next 20 years, according to projections from the Australian Bureau of Statistics”.

This is why I describe mass immigration as a ‘ponzi scheme’.

Importing more migrants to solve ageing is ‘can-kick economics’, because today’s migrants will grow old, creating further ageing problems in 40 years’ time.

Moreover, the 13 million extra people projected in Australia over the next 38 years will be driven entirely by net overseas migration—directly as they arrive by plane and indirectly as migrants have children.

This enormous population increase will all require massive sums of spending on economic and social infrastructure, such as schools, hospitals, roads, public transport, aged care, water supplies, energy networks, etc.

These costs can obviously be avoided by not running a mass immigration program in the first place.

Detailed counter-arguments to the notion of importing migrants to solve population ageing were articulated in the 2019 research paper Three Economic Myths about Ageing: Participation, Immigration and Infrastructure, which was authored by myself and Dr Cameron Murray.