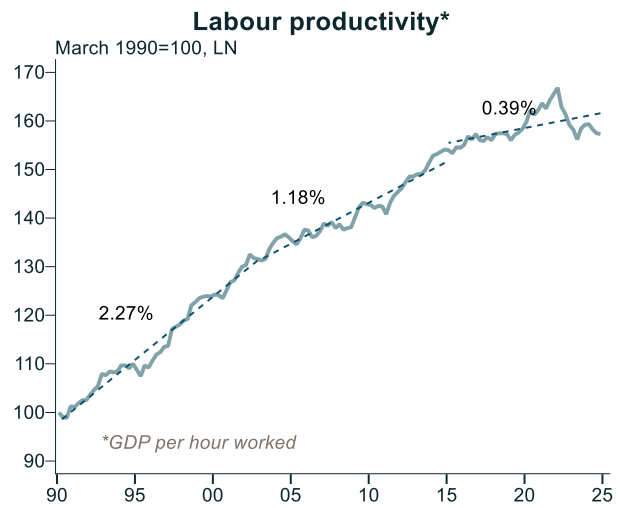

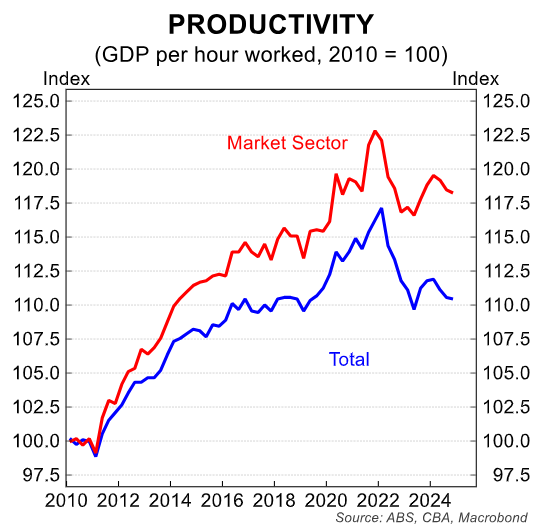

The continuing decline in Australia’s productivity was one of the most important data points from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Q4 national accounts released this week.

Labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) fell by 0.1%, which follows declines of 0.7% and 0.5% in the previous two quarters, respectively.

This lowered Australia’s labour productivity to December 2016 levels, with the decade average growth slumping to only 0.39%, according to Alex Joiner from IFM Investors.

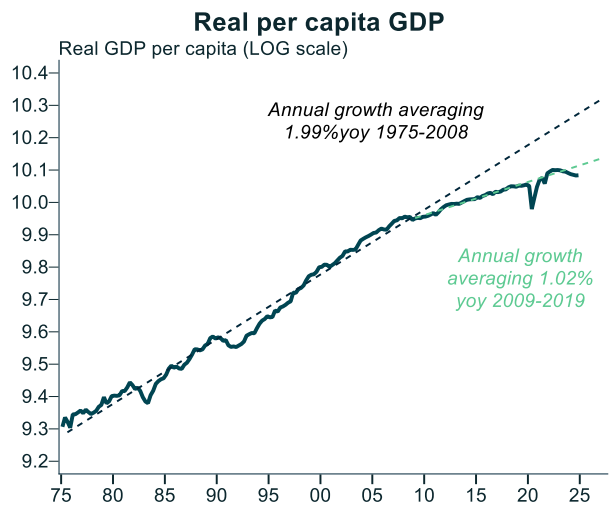

The slump in Australia’s labour productivity growth explains the real per capita GDP growth decline.

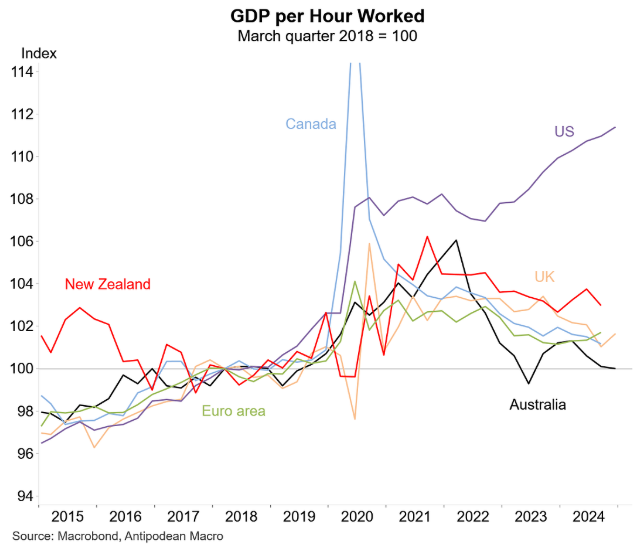

As Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro plots below, Australia has experienced the lowest labour productivity growth among Anglo and European nations since 2018.

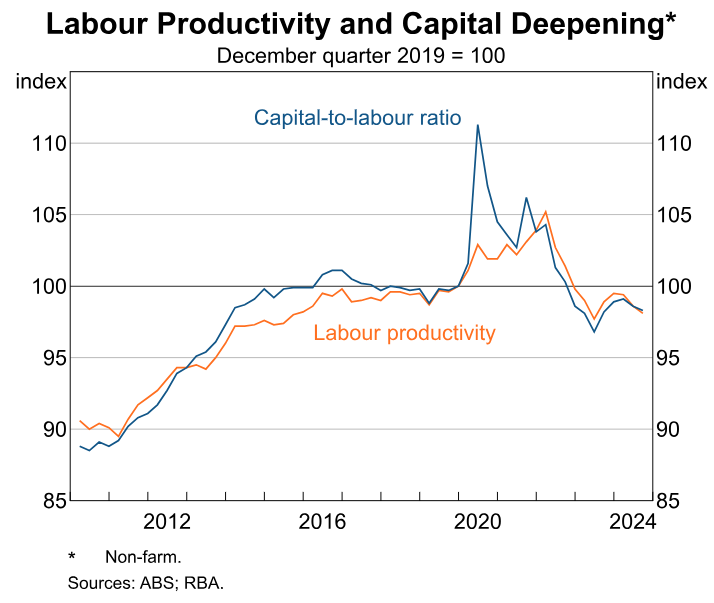

As explained last week by the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) Michael Plumb, part of the productivity collapse has been driven by ‘capital shallowing’—i.e, the population via immigration has grown faster than business and infrastructure investment.

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”, Plumb said.

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy – or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”.

“Capital per worker was broadly unchanged for around five years leading up to the pandemic and – looking through the volatility in the data during the pandemic – is currently a bit below those levels”.

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong growth in employment”, Plumb said.

Ross Gittins also explicitly singled out persistently high immigration as a significant cause of Australia’s declining productivity:

“If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up”.

“In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening”.

“Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states”.

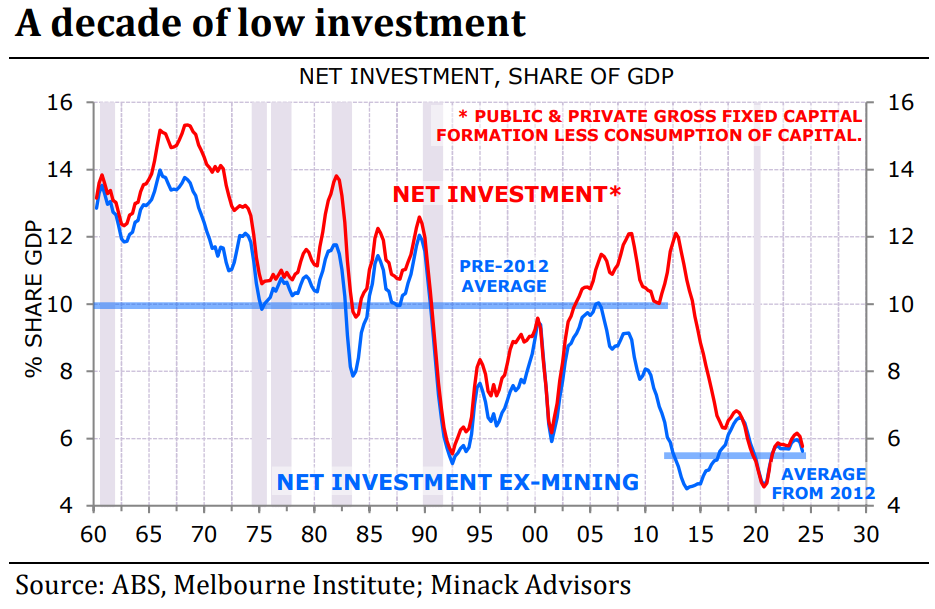

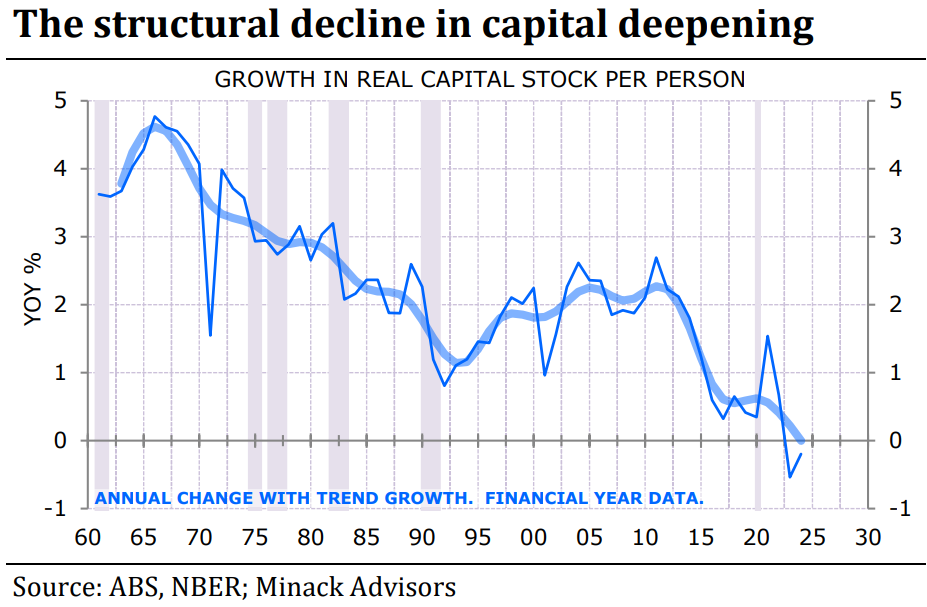

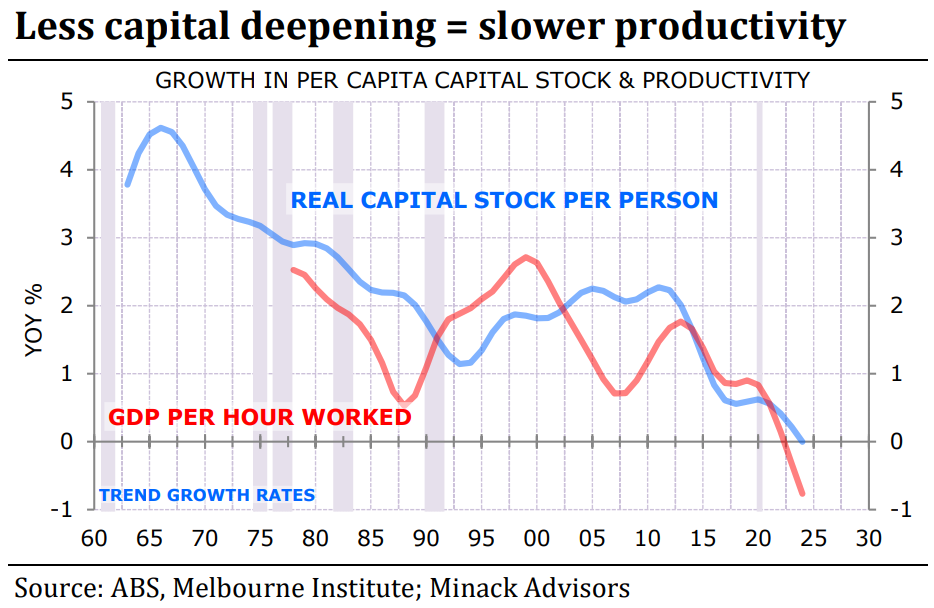

Gerard Minack’s seminal report on the issue noted that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

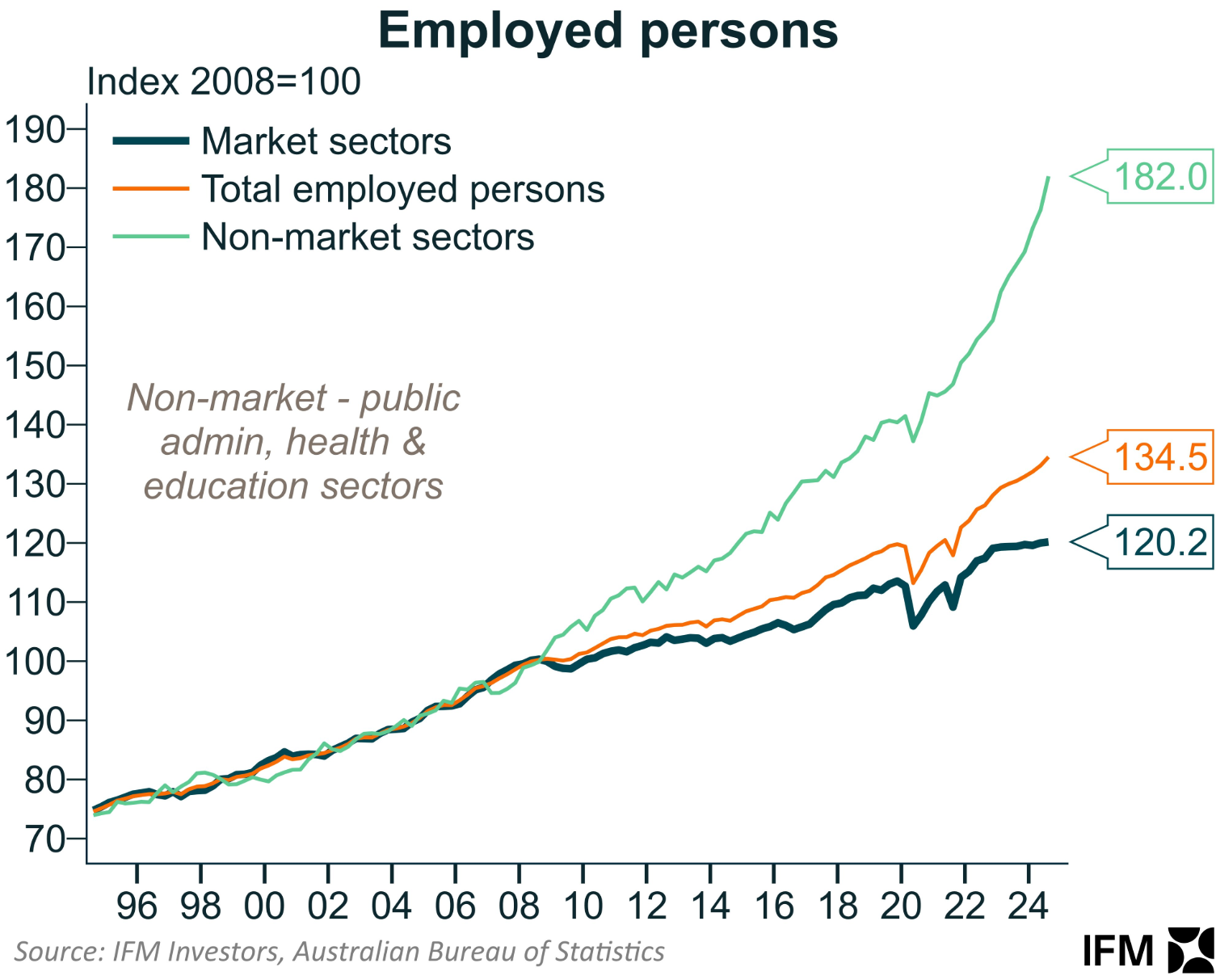

The second major driver of Australia’s recent productivity decline is the expansion of the non-market economy, principally via the NDIS.

Employment in the non-market (government-aligned) sector has grown by more than 80% since the GFC in 2008, versus only 20% growth in the market sector.

The Q4 national accounts showed that productivity growth has been strong in the market sector, but poor in the non-market sector.

Therefore, expanding the non-market sector has contributed heavily to Australia’s productivity decline.

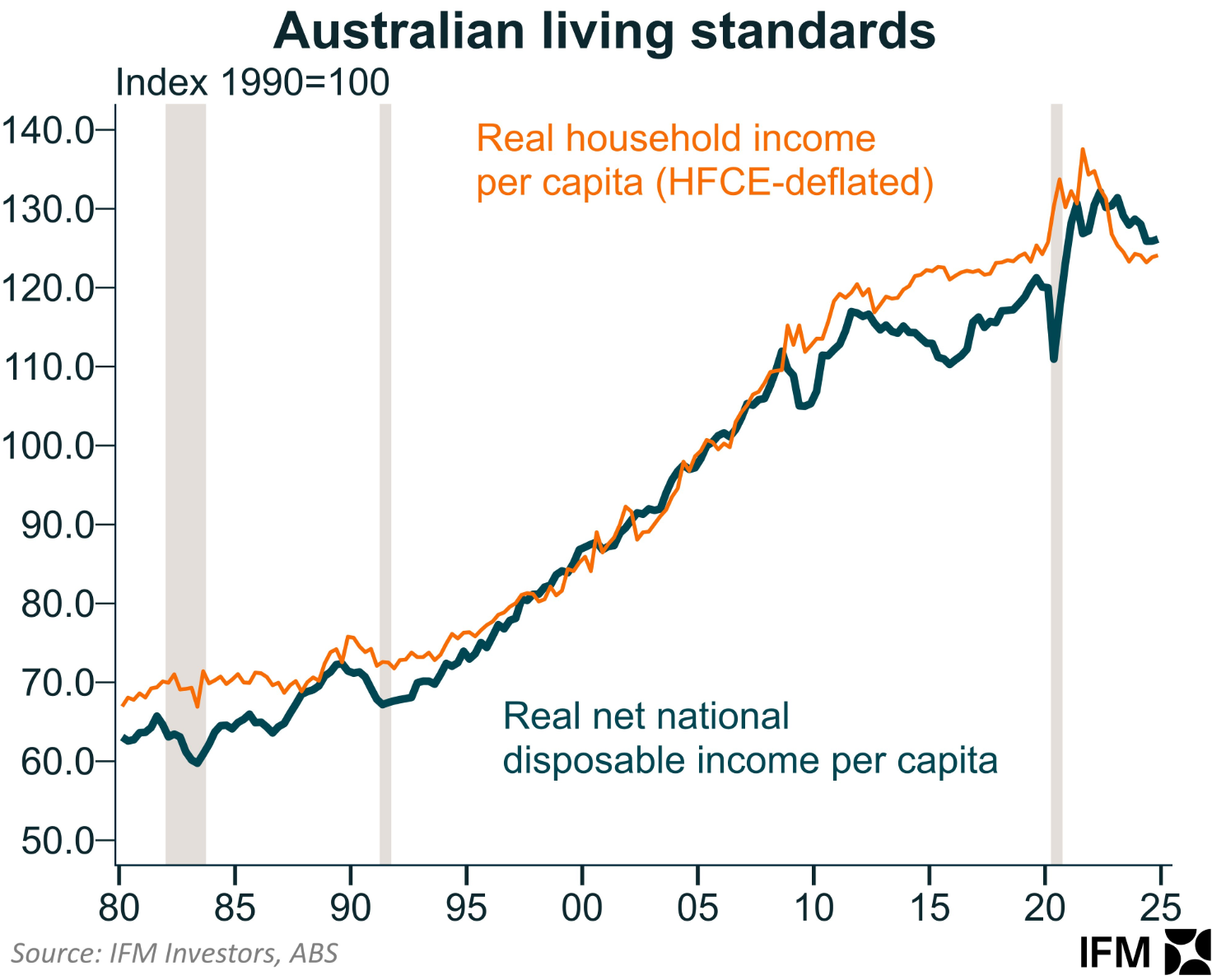

If Australia’s productivity continues to flounder, so will Australian living standards.