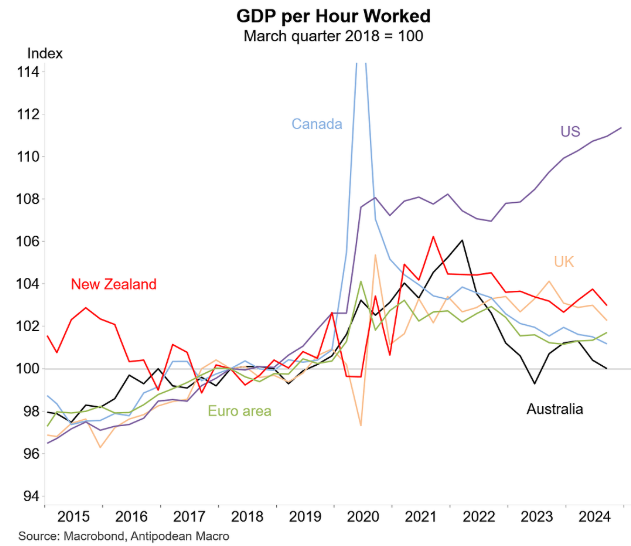

Last month, Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro posted the following chart tracking labour productivity across major advanced nations.

As you can see, Australia’s labour productivity growth has been among the worst in the advanced world after recording zero improvement since 2016.

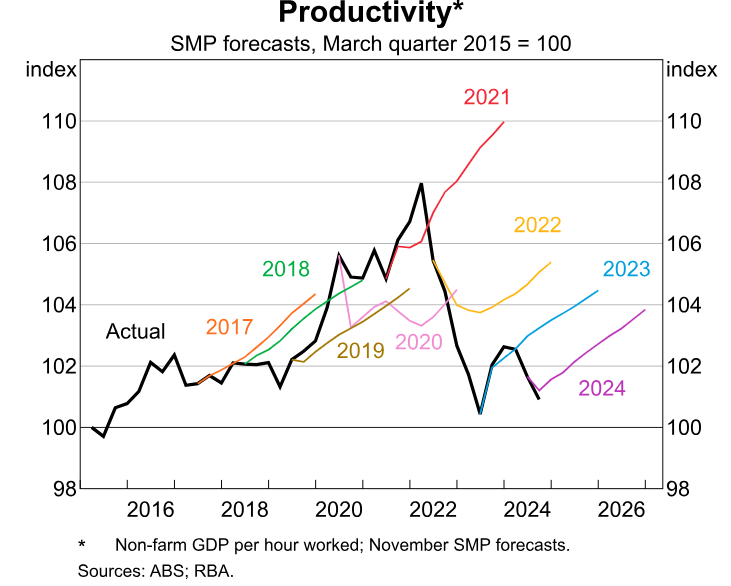

Last week, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) Michael Plumb delivered a speech to a meeting of the Australian Business Economists, which admitted that the RBA’s forecasts of productivity growth have been too optimistic for a decade.

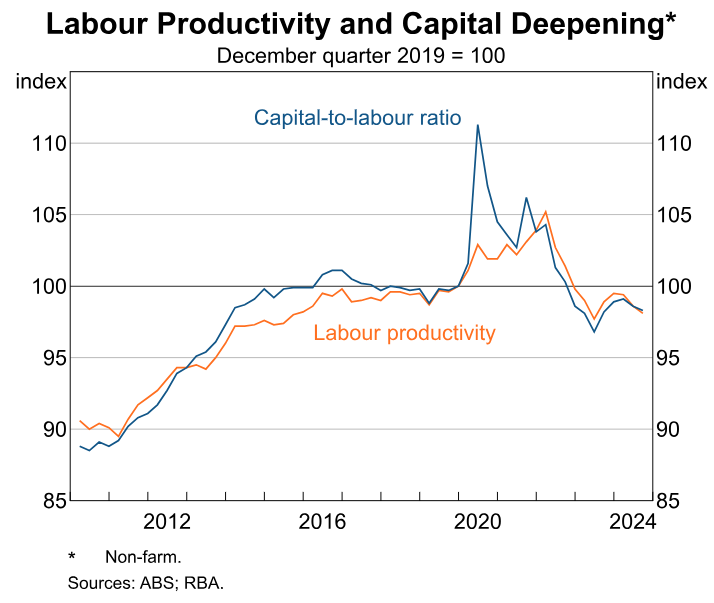

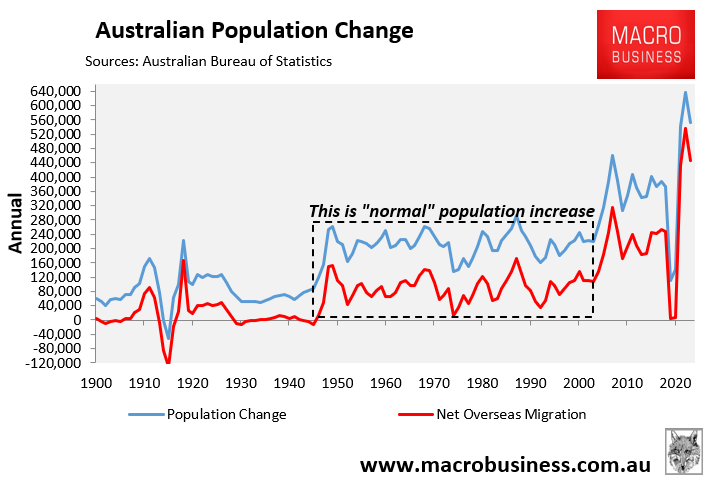

Plumb also tacitly admitted that Australia’s mass immigration policy has eroded productivity via the process of ‘capital shallowing’—i.e’., the population has grown faster than business and infrastructure investment.

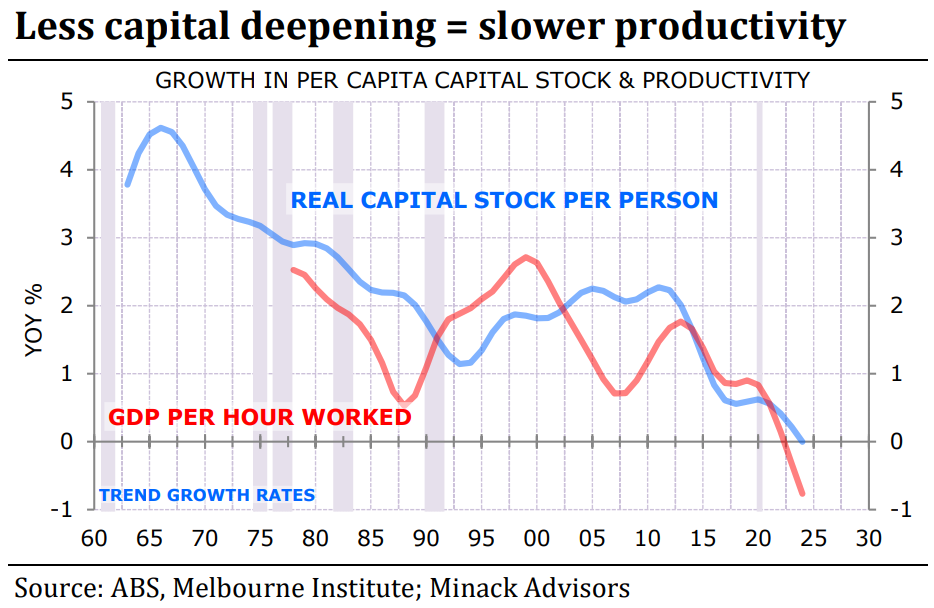

“Labour productivity depends on two things”, Plumb said. “The first is how much capital each person has to work with. Providing workers with more or better capital – like machines or faster computers – can increase the amount of output each worker produces. This is referred to as ‘capital deepening’”.

“The second is MFP. Improving MFP involves finding new ways to combine labour and capital to produce more output”.

“The slow growth in labour productivity over recent years has reflected slow growth in both MFP and the amount of capital available to each worker”, Plumb said.

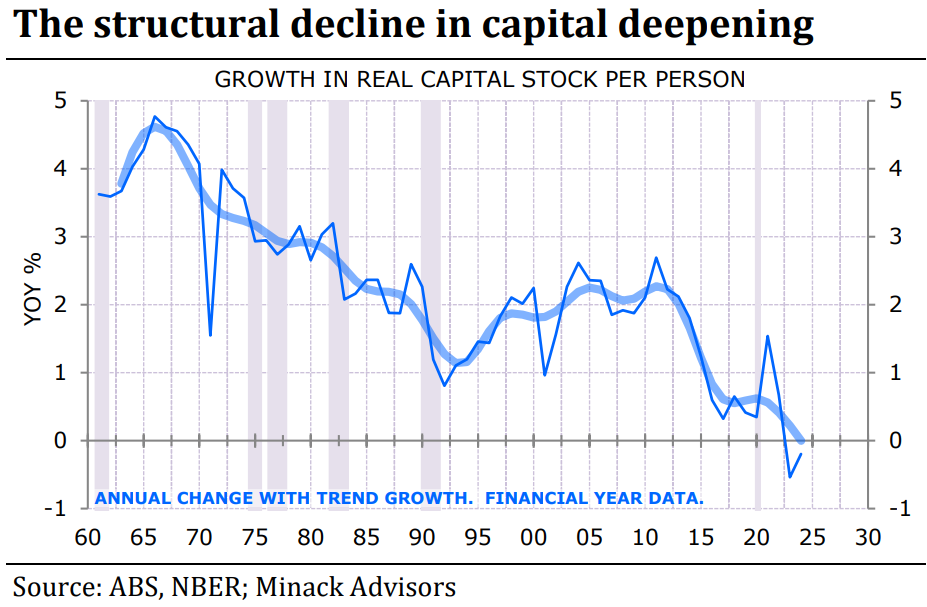

“Slow growth in the amount of capital available for each worker in the Australian economy – or a lack of ‘capital deepening’ – has contributed to slow growth in labour productivity”.

“Capital per worker was broadly unchanged for around five years leading up to the pandemic and – looking through the volatility in the data during the pandemic – is currently a bit below those levels”.

“In other words, overall investment has not kept pace with the strong growth in employment”, Plumb said.

Ross Gittins’ latest article explicitly singled out persistently high immigration as a major cause of Australia’s declining productivity:

“Almost to a person, economists are great believers in high rates of immigration. Immigration, they keep telling us, is great for economic growth. It’s true. There’s no easier way to grow an economy than to increase the number of people in it”…

“As all the economists were taught at uni but keep forgetting to mention to the punters, the claim that immigration raises our material standard of living – which is the oft-stated benefit of economic growth – comes with a big proviso”.

“Which is? Productivity. If you get more people, but fail to provide them with the same capital equipment as the rest of us have – extra machines for the extra workers, extra houses for the extra families, and extra roads, public transport, schools and hospitals for the extra families – everyone’s standard of living goes down, not up”.

“In economists’ jargon, you have to ensure immigration doesn’t cause a decline in the “capital-to-labour ratio”. As well as the spending on “capital deepening” needed to raise our productivity, you also need spending on “capital widening” merely to stop our productivity worsening”.

“Guess what? We’ve had years of high immigration without the increased capital spending to go with it. Part of the problem is that the level of government with control over immigration, the feds, is not the level of government with responsibility for ensuring adequate additional investment in public infrastructure, the states”.

Independent economist Gerard Minack explained the immigration-productivity nexus in detail last year.

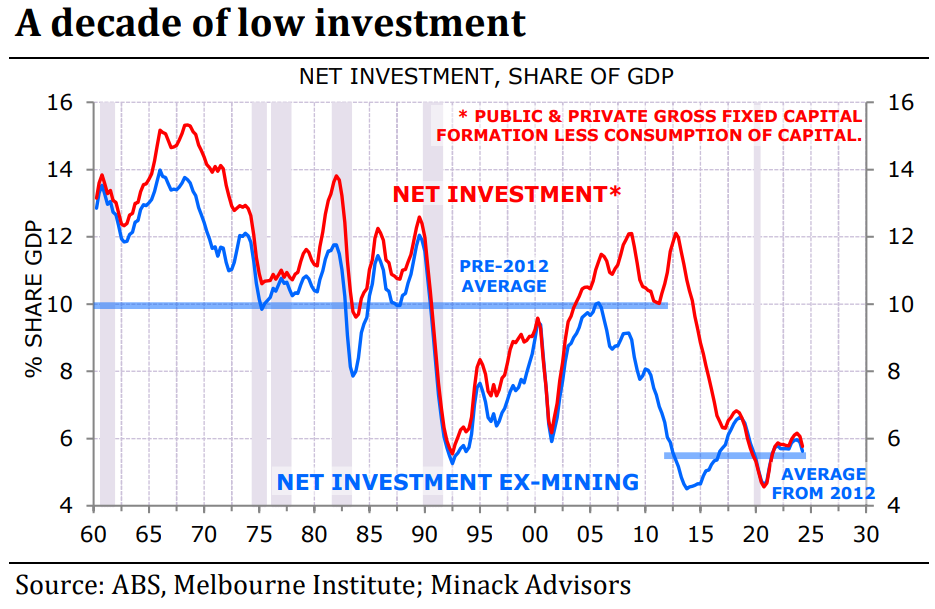

Minack noted that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

This “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

The situation is unlikely to change.

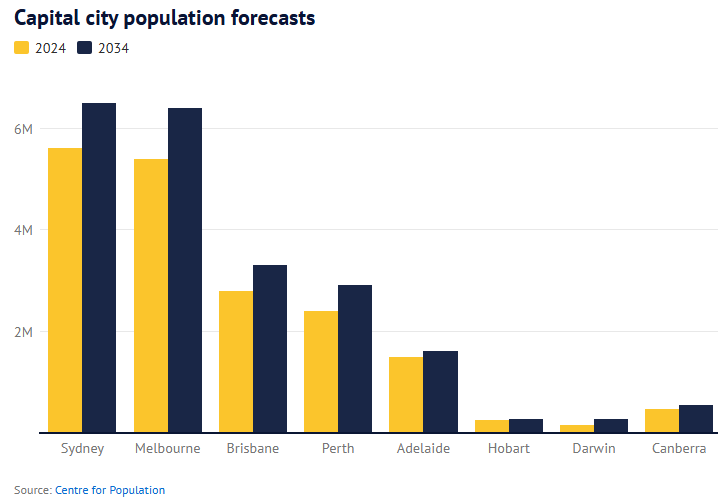

Treasury’s Centre for Population projected that Australia’s population will expand by 4.1 million over the coming decade, with most of this growth landing in the major cities.

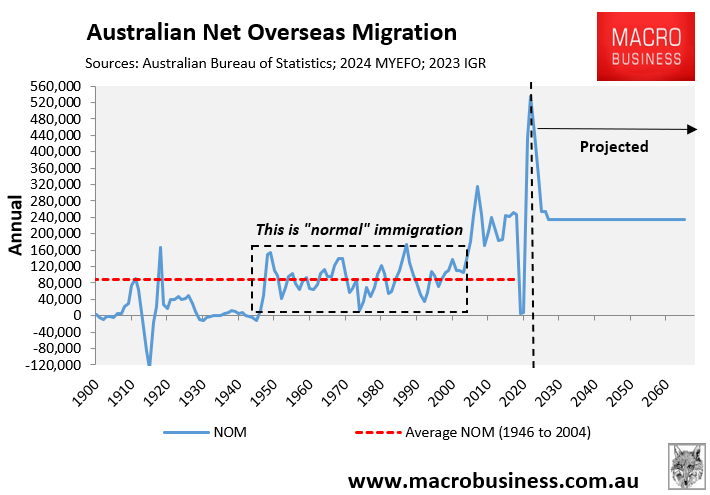

The latest Intergenerational Report projects that Australia’s population will balloon by around 13 million people (circa 50%) in 38 years, driven by permanently high net overseas migration.

The end result is the Australian economy will remain caught in a productivity trap because the federal government continues to run an excessively high immigration program that consistently exceeds business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

Now that the RBA has identified the problem, will it pressure the federal government to slow the rate of immigration?

Don’t hold your breath.