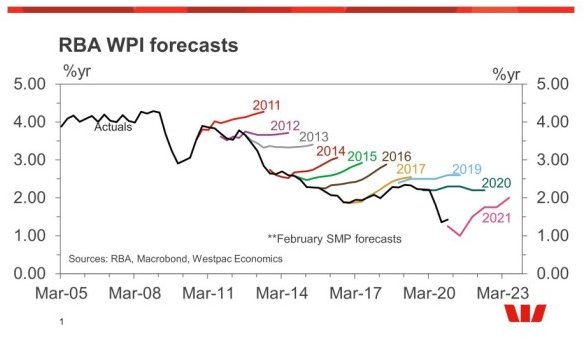

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has been notoriously poor at forecasting Australian wage growth.

For the past 15 years, the RBA’s Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP) has consistently forecast higher wage growth than realised.

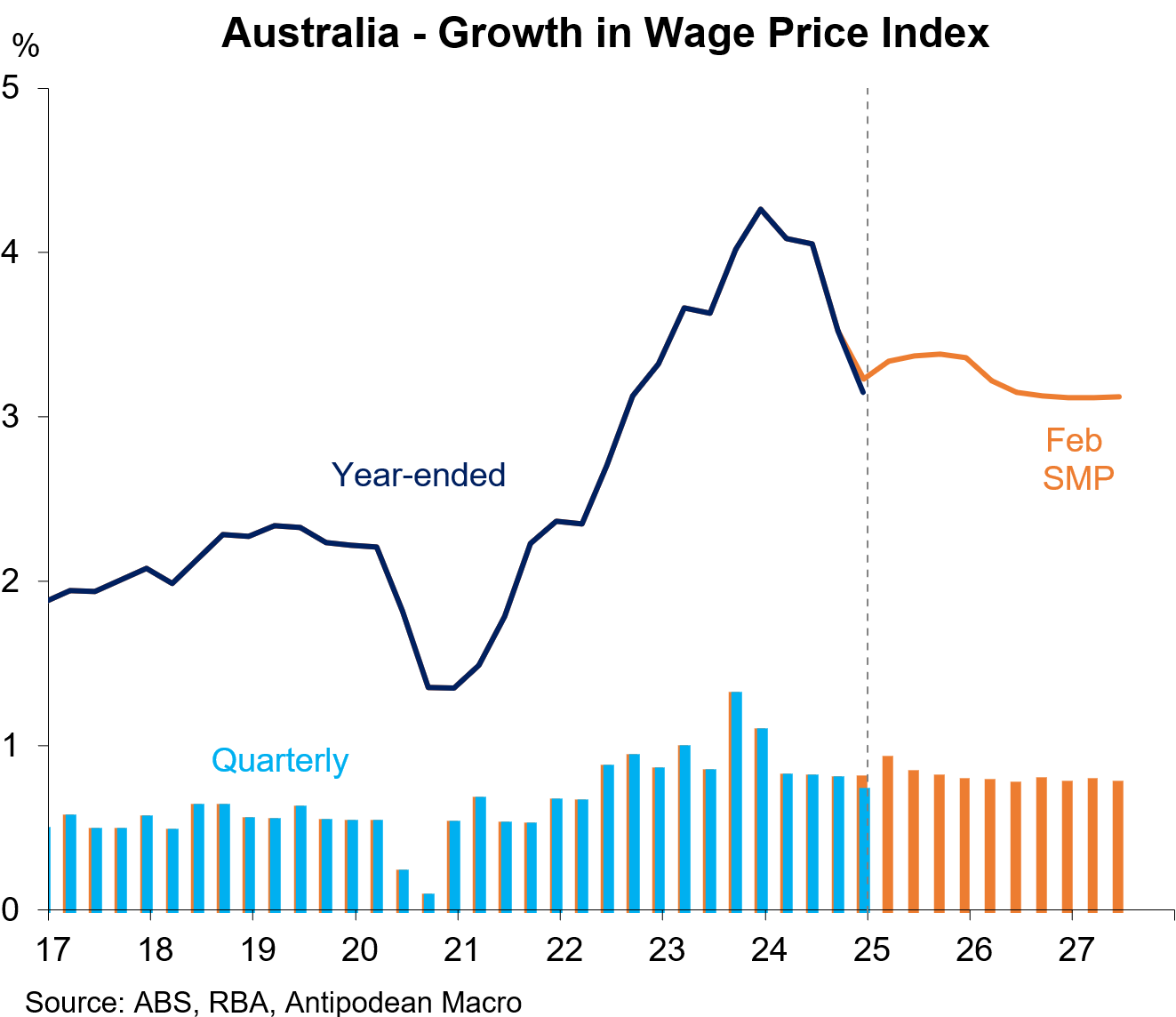

The RBA looks to be making the same mistakes, with Australian wage growth now falling despite Australia’s low unemployment rate of 4.1%.

Wage growth is already tracking below the RBA’s latest SoMP, released only last month.

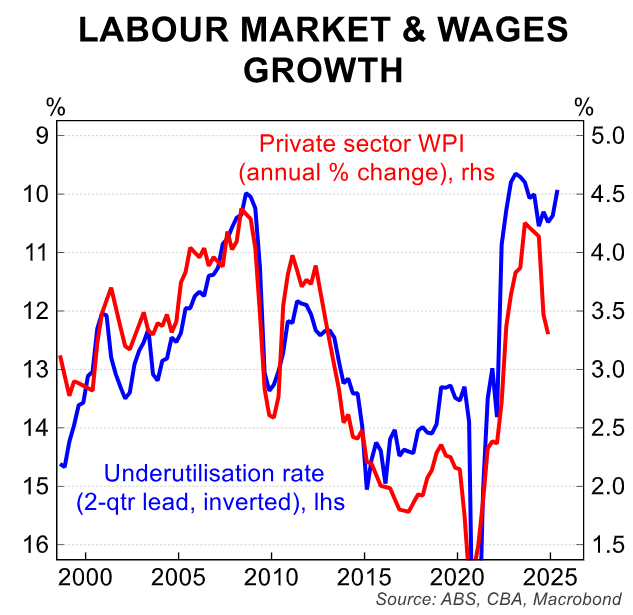

One of the reasons why the RBA continues to be too bullish on wage growth is because its “non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment”, or NAIRU, is consistently too high at 4.5% currently.

The NAIRU, or ‘full employment, is the maximum level of employment consistent with holding inflation within the RBA’s 2% to 3% target.

Therefore, an unemployment rate of 4.1% should see wage growth rising, not falling.

The Treasurer, several economists, and the ACTU have argued that the historically low unemployment rate of 4.1% in February can be maintained without reigniting wage and inflation pressures, which are now moderating.

“Despite the strength of the labour market, wages growth is easing, suggesting the NAIRU is lower than where the RBA has it pegged at ~4.5%”, CBA economist Harry Ottley wrote in his latest note.

“This dynamic suggests if the disinflation process continues as we expect, the labour market is not a significant source of upward inflation pressure, and further RBA rate cuts are likely in 2025”.

“The share of employed persons who have multiple jobs rose to another record high of 7.71% in Q4 2024. The size and importance of the gig economy is increasing flexibility in the labour market”.

“Work from home and other measures such as increased childcare subsidies that are boosting participation are also having an impact. Cost-of-living pressure may also be contributing”.

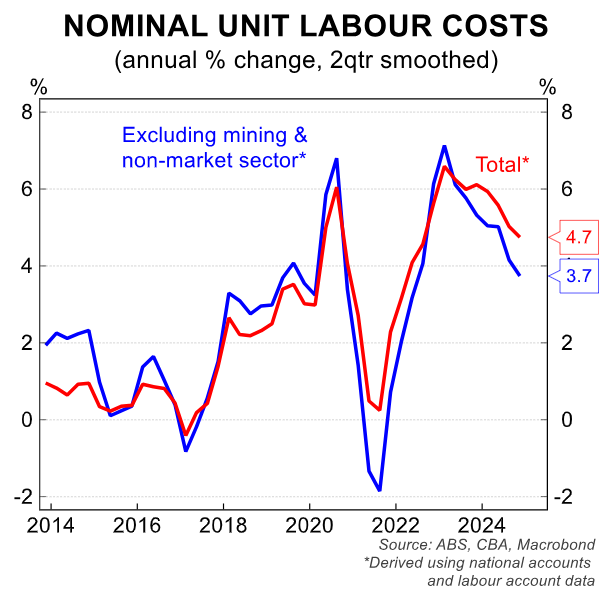

“Excluding the non-market sector (where there is often a lack of market prices, and wages are heavily subsidised by Government) and the mining sector (where this is little pass through of wages pressure to inflation and productivity is in structural decline), shows nominal unit labour costs are at a more comfortable albeit still elevated level”, Ottley wrote.

Clearly, the RBA is too bullish on the NAIRU and wage growth—a position that it has held for more than a decade.

The never-ending supply shock of mass immigration acts as a constraint on Australian wage inflation.