CBA’s excellent economics team has provided a comprehensive analysis of the federal budget. Below are key extracts broken down by theme.

Overview:

In the near term, the key economic and fiscal aggregates in the 2025-26 Budget are largely unchanged from the last official update in December, and broadly in line with our own forecasts.

The Budget suggests the economy has ‘turned a corner’ with growth strengthening and underlying inflation continuing to fall.

The budget deficit in 2024-25 is expected to be $27.6bn before widening to $42.1bn in 2025-26. We do not expect the Budget to have a material impact on the expected short-term path of underlying inflation or interest rates.

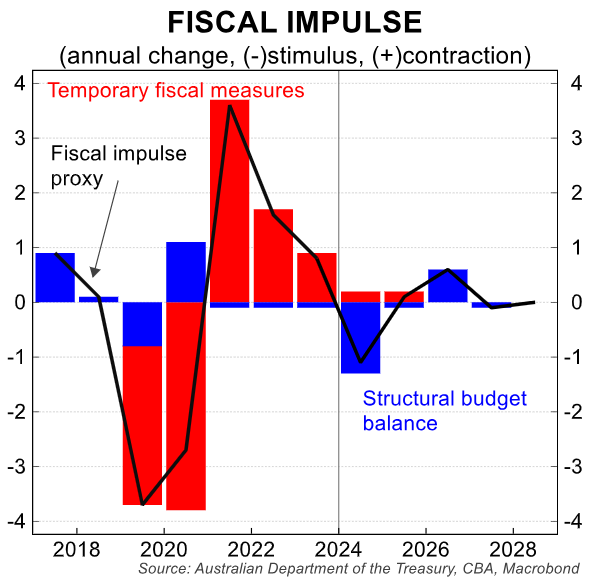

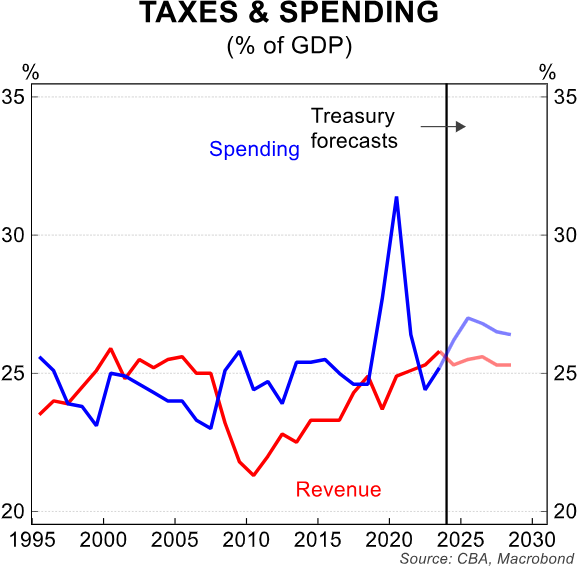

However, the Government has chosen to hand out around $35bn in new tax cuts and spending over the forward estimates, rather than banking a projected windfall from a stronger labour market and nominal economy. This sees the structural budget position continue to deteriorate over the medium term and increases the risk that the deficit will widen further in coming years if assumed savings and higher revenue do not eventuate.

The centrepiece of the Budget is a surprise new tax cut for all taxpayers, by reducing the first marginal tax rate from 16% to 14% over two years from 1 July 2026, at a cost of $17.1bn over five years.

The Budget contains a range of previously announced healthcare initiatives, including $8.4 billion in bulk-billing incentives. It also extends existing energy bill rebates of $75 per quarter for all households and eligible small businesses until the end of calendar year 2025.

These costs are largely offset by higher tax receipts, flowing from a stronger labour market and reduced growth in disability and other ongoing spending.

Treasury has upgraded its wages forecast to 3¾% in 2025-26 and now expects the unemployment rate to peak lower at 4¼%, rather than 4½%.

Major policy announcements:

Last year, the Budget was heavily focused on the Future Made in Australia policy. This year, policy announcements are primarily directed at reducing cost-of-living pressures.

As noted above, the main surprise in the Budget came in the form of an income tax cut which lowers the marginal tax rate on the lowest tax threshold ($18,201-$45,000) from 16% to 15% in July 2026 and then again to 14% from July 2027. This was the largest new policy in terms of the cost to the budget.

The next most significant measure in terms of impact on the budget bottom line was the $8.5bn uplift (over five years) in spending to support improved bulk-billing rates. This had already been announced.

These two policies account for ~75% of the additional spending decisions taken between MYEFO and tonight’s Budget. Some of the major announcements since the December 2024 MYEFO included in tonight’s budget are listed below.

Cost of living

- $17.1bn over five years to deliver an income tax cut for all taxpayers. The marginal tax rate for the bottom tax bracket will be lowered from 16% to 15% from 1 July 2026 and then to 14% in 1 July 2027. This will provide an average wage earner with an additional $268 a year in 2026-27 and $536 a year in 2027-28.

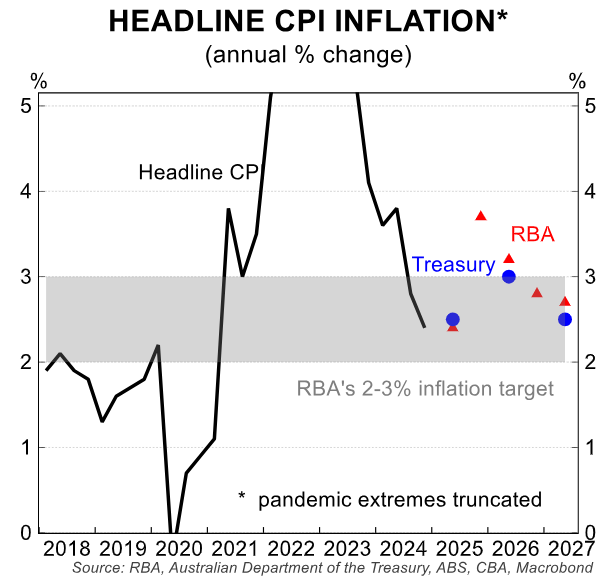

- $1.8bn to extend electricity rebates for six months. The Government anticipates this extension to electricity rebates to reduce annual headline CPI inflation by 0.5ppts in Q4 25.

Health

- $8.4bn over four years to increase doctor’s incentives to boost bulk-billing rates in Australia. The policy aims to increase the proportion of doctor visits that are bulk billed to 9 in 10, assisting with the cost-of-living.

- $689m on limiting the price of medicines on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) to less than $25 per script. This is another policy aimed at easing heath costs for individuals and reducing the cost-of-living for households.

- $793m for women’s health initiatives including new contraceptive pills and menopause treatments being added to the PBS. Additional support for endometriosis patients is also included.

Infrastructure

- $7.2bn to upgrade the Bruce Highway, noting the project will not be completed until 2032 and much of the funding is not included in the forecasts for the next five years. Overall, the Government has identified new infrastructure priorities that will add $1.8 billion to spending over five years, while also identifying around $4.6bn in payment reductions from within the infrastructure program, reflecting project slippage.

Education

- Pending successfully passing the legislation, the Government remains committed to cutting existing student debt by 20%. While the Government flags this is cost-of-living support, the impact is muted due to it reducing the amount of debt rather than providing extra money in the pocket of students.

- The Government will increase the amount that people can earn before they are required to start paying back their loans from $54,435 in 2024–25 to $67,000 in 2025–26. This is ‘off balance sheet’ and so does not impact the underlying cash balance but will provide modest cost-of-living relief to recent graduates.

Housing

- An additional $800m will go towards expanding the Help to Buy Scheme by increasing the income caps for eligibility to $100,000 (from $90,000) and $160,000 (from $120,000) for single and joint applicants, respectively. Under the help to buy scheme, the Government provides first home buyers with between 30-40% of the purchase cost of a property, with only a 2% deposit required from buyer. It is capped at 10,000 places per year.

Industrial relations

- There was a surprising policy reform included in the Budget that limits non-compete clauses in the hope of boosting wages and mobility. The policy is limited to low-and middle-income workers and Treasury estimate this could increase wages by 4% or $2,500 per year for affected workers.

Small Business

- Policies specifically targeted atsmall businesses are modest in this Budget. The main announcement was that eligible small business will have their previous electricity rebate extended by six months, delivering an additional $150 in total. This will benefit around one million businesses and was announced in advance of Budget night.

- The hospitality sector and alcohol producers will benefit from a pausing of indexationon draught beer excise and excise equivalent customs duty rates and by increasing support available under the existing excise remission scheme. The cost of these measures will be $165m over five years.

Economic forecasts

As is the custom, the Budget provides detailed economic forecasts for the Budget year and the subsequent financial year, with economic projections for the following two years. Our key focus is on the Government’s detailed economic forecasts.

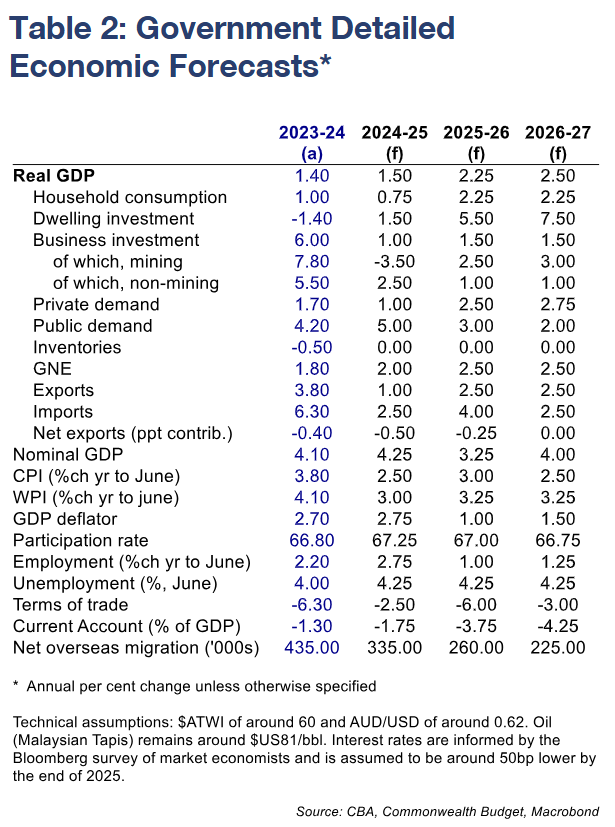

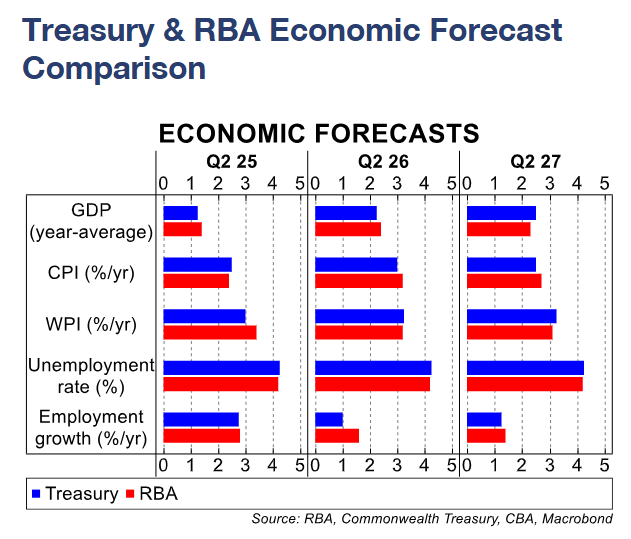

On the activity side of the economy, the Government has forecast real GDP growth of 1.5% in 2024/25, strengthening to 2.25% in 2025-26. The forecast for 2024/25is a little lower than the Government expected in the December MYEFO (0.25ppts), but this reflects the direct loss of economic activity from ex-Tropical Cyclone Alfred.

Our forecast for GDP growth in 2024/25 is 1.4%, so we are closely aligned with the Government’s near-term assessment for economic growth. In 2025-26, our forecast for GDP growth steps up to 2.3% and is essentially the same as the Budget forecast of 2.25%. So,over the forecast horizon that we cover we see growth following an essentially identical trajectory to the Government.

Importantly, the Government has downwardly revised its peak in the unemployment rate from 4.5% to 4.25%. This brings their forecast more into line with our own. We currently put the peak in the unemployment rate at 4.3% in H2 25, before moving a touch lowerover 2026 as the lagged impact of further expected interest rate cuts supports economic activity and private job creation.

The Budget forecasts employment growth of 2.75%/yr in Q2 25, slowing down to 1.0%/yr in Q2 26 before rising to 1.25%/yr in Q2 27. The participation rate is forecast to drift down a little, which means the unemployment rate essentially crabs sideways over the forecast horizon.

The RBA has a similar profile for the unemployment rate as the Government, with the unemployment rate peaking at 4.2%. However, the RBA forecast the annual rate of trimmed mean CPI to settle at 2.7% from mid-25 throughout its forecast horizon, which extends to mid-27.

The Government does not publish forecasts for the trimmed mean CPI. But the Government expects the annual rate of headline inflation to settle at 2.5% over the medium term. The upshot is that there remains a divergence of view between the Government and the RBA on underlying inflation trends, most likely related to different views on the NAIRU.

The Government puts the NAIRU at 4.25%, whilst the RBA consider it more likely to be around 4.5%. Wethink the NAIRU is more likely to be ~4.0% given recent wages and inflation outcomes.

On the Government’s inflation forecasts specifically, the extension of the Federal energy bill rebates shifts our quarterly track for headline inflation (and lowersour end-25 forecast from 3.2%/yr to 2.9%/yr). But it doesn’t change our forecast for headline inflation in Q2 26, which we have at 2.9%/yr.

More importantly, we leave our profile for the monetary policy relevant trimmed mean CPI unchanged (we have trimmed mean CPI essentially at the mid-point of the RBA’s target band from Q2 25 over our forecast horizon). This underpins our central scenario for the RBA to continue normalising the cash rate over 2025 (our base case sees 75bp of further interest rate cuts in 2025 for an end year cash rate of 3.35%).

Here it is important to note that the ABS will publish the February monthly CPI indicator at 11.30amon Wednesday 26 March. This will provide us with a much clearer steer on where the all-important Q1 25 trimmed mean CPI is likely to print.

Annual wages growth, as measured by the wage price index, is forecast by the Governmentto be 3.0% in Q2 25. This is materially below the RBA’s forecast of 3.4%. The economic forecasts in the Budget are rounded to the nearest quarter point. But even if we account for a slightly potentially stronger forecast of say 3.1% from the Government in Q2 25, the differenceis still significant.

In short the Government expects wages growth to be materially weaker than the RBA over the next two quarters. We have a similar forecast to the Government on the near-term outlook for wages growth (we put the WPI at 3.1%/yrin Q2 25).

Further out, the Fair Work Commission decision on the minimum and award wage, to be handed down before 30 June 2025, will be important to the wages outlook in 2025/26. Our expectation is that the award wage increase is ~3.0% (i.e. ~0.75ppts lower than the 2024 outcome).

Whilst we generally don’t put a lot of weight on the Government’s economic forecasts beyond two years, the projections for wages growth and inflation in 2027/28 and 2028/29 pose some interesting questions. The annual rate of wages growth is projected to reaccelerate to 3.75% by mid-29, despite the headline CPI holding firm at 2.5% from mid-2027 to mid-2029. The Government is therefore projecting that real wages growth lifts to a whopping 1.25%. And throughout that period the unemployment rate is projected to remain flat at 4.25%. A big lift in productivity growth is assumed. But it is not clear what underpins that assumption.

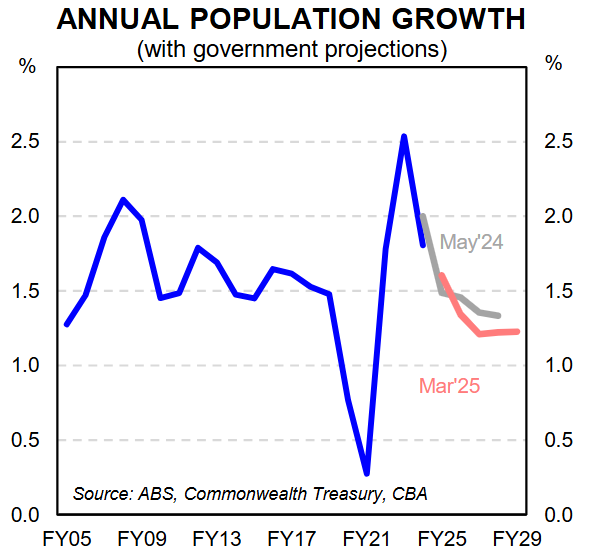

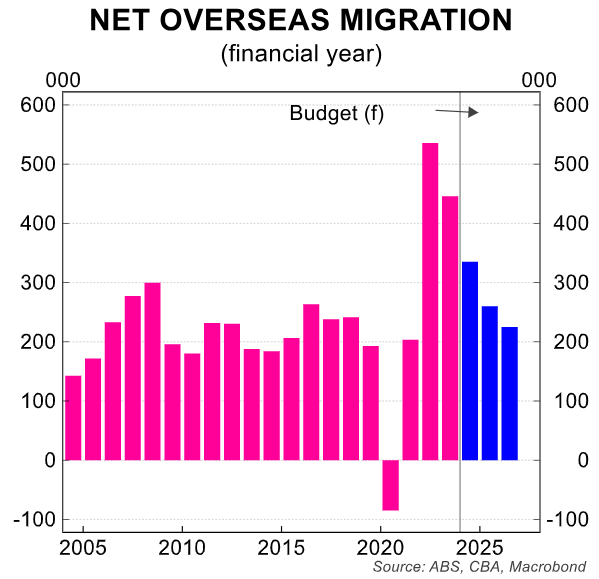

Population growth is a key assumption in the Budget, which is in turn driven by forecasts for net overseas migration (NOM). It is widely known the NOM was much stronger over recent years than the Government expected. Recent data from the ABS indicates that population growth is slowing, albeit it is still higher than most other advanced economies (population grew by 1.8%/yr in Q3 24).

The Budget assumes that annual NOM slows to 335k by Q2 25 (5k less than MYEFO) and to 225k by Q2 27. (Note that these NOM forecasts do not incorporate the latest population data, which were for Q3 24). As a result, population growth is forecast to slow to 1.6%/yr by Q2 25 and 1.2%/yr by the outer years. We take the Government’s population forecasts at face value and we use the same assumption in our forecast profile for the economy.

Risk of escalation in trade tensions

The Budget papers include a break-out box on the impact on Australia from the escalation in global trade tensions, particularly the US. The analysis suggests that the overall risk to Australian exporters from escalations in global trade tensions remains low as an Australian dollar depreciation acts as a safety net and firms are “very adept at finding alternative markets for Australian exports”.

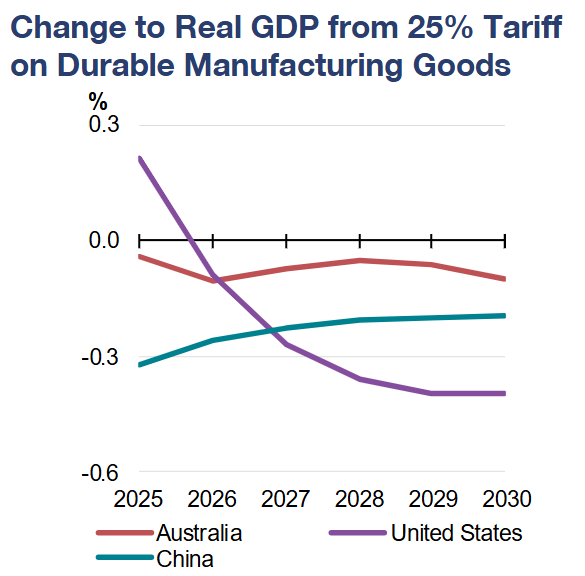

In the Budget, a 25% tariff on durable Australian manufacturing goods by the US is analysed. In this scenario the impact on the Australian economy is estimated to be modest, with real GDP dipping by approximately -0.1% by 2030.

The indirect effect is forecast to be nearly four times as large due to flow on impacts to trade between Australia, China and the US. For inflation, the US would be far worse off, experiencing a persistent increase in inflationary pressure over the period to 2030.

Comparatively, Australia would likely experience a small temporary inflation rise (increasing by 0.1% in 2025), offset over time by a depreciating Australian dollar enhancing competitiveness.

The Budget analysis finds that retaliatory tariffs from all countries would worsen the real GDP loss globally (falling by -0.2% in Australia and -0.6% in the US by 2030) and heighten inflationary pressures (increasing by 0.2% in 2025 in Australia and 1.2% in the US).

Commodity and nominal GDP forecasts

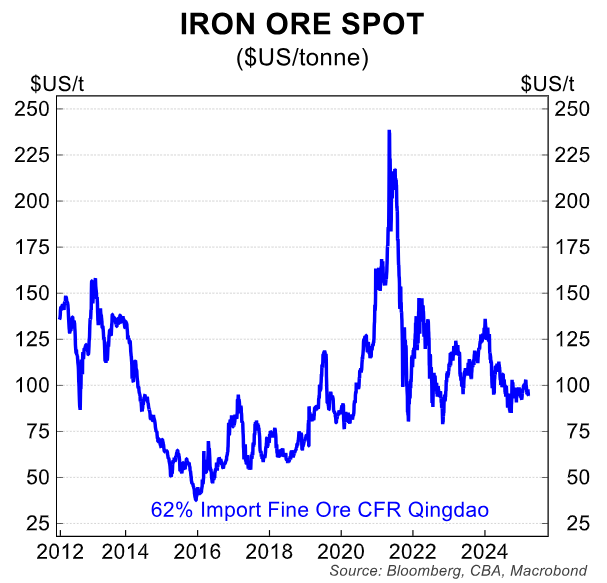

The Budget maintained most of their long-run price assumptions relative to MYEFO. Long-run iron ore, coking coal, thermal coal and LNG were unchanged at $US60/t, $US140/t, $US70/t and $US10/mmbtu respectively.

The time it will take for the Budget’s long run prices to be reached from current levels was also left unchanged at 4 quarters. Therefore, the Budget expects long run commodity prices to be realised by the end of Q1 2026 –6 months after the MYEFO’s forecast.

Like the MYEFO, oil was a notable exception. Oil prices (TAPIS benchmark) were forecast to remain at $US81/bbl for the foreseeable future.

The Budget’s commodity price outlook is conservative to our forecast in 2025-26. We see iron ore, coking coal and thermal coal prices average 22%, 53% and 40% higher than the Budget’s outlook next financial year respectively. This comfortably offsets our view of lower oil and LNG spot prices compared to the Budget.

In 2026-27 and 2027-28, the Budget’s commodity price outlook still appears conservative relative to our view. The Budget’s coking coal and iron ore price outlook looks particularly low. We believe coking coal markets will remain tight this decade given limited coking coal supply growth and the ongoing coking coal use in steelmaking.

However, the recent plunge in coking coal prices highlights potential downside risks to our price view. We see iron ore prices decline slowly to ~$US80/t (62% Fe, CFR China) by Q1 2027 –implying both a higher long-run price and more gradual fall than the Budget’s outlook.

We see a gradual increase in seaborne supply driving a gradual fall in iron ore prices over the medium-term.

Conversely, the Budget’s oil price outlook looks too high relative to our forecast in 2026-27 and 2027-28. We see oil prices falling in coming years as the uptake of electric vehicles dents global oil demand.

The Budget’s LNG and thermal coal price outlook broadly converges with our price forecast for both commodities in 2026-27 and 2027-28.

Key Budget and debt numbers

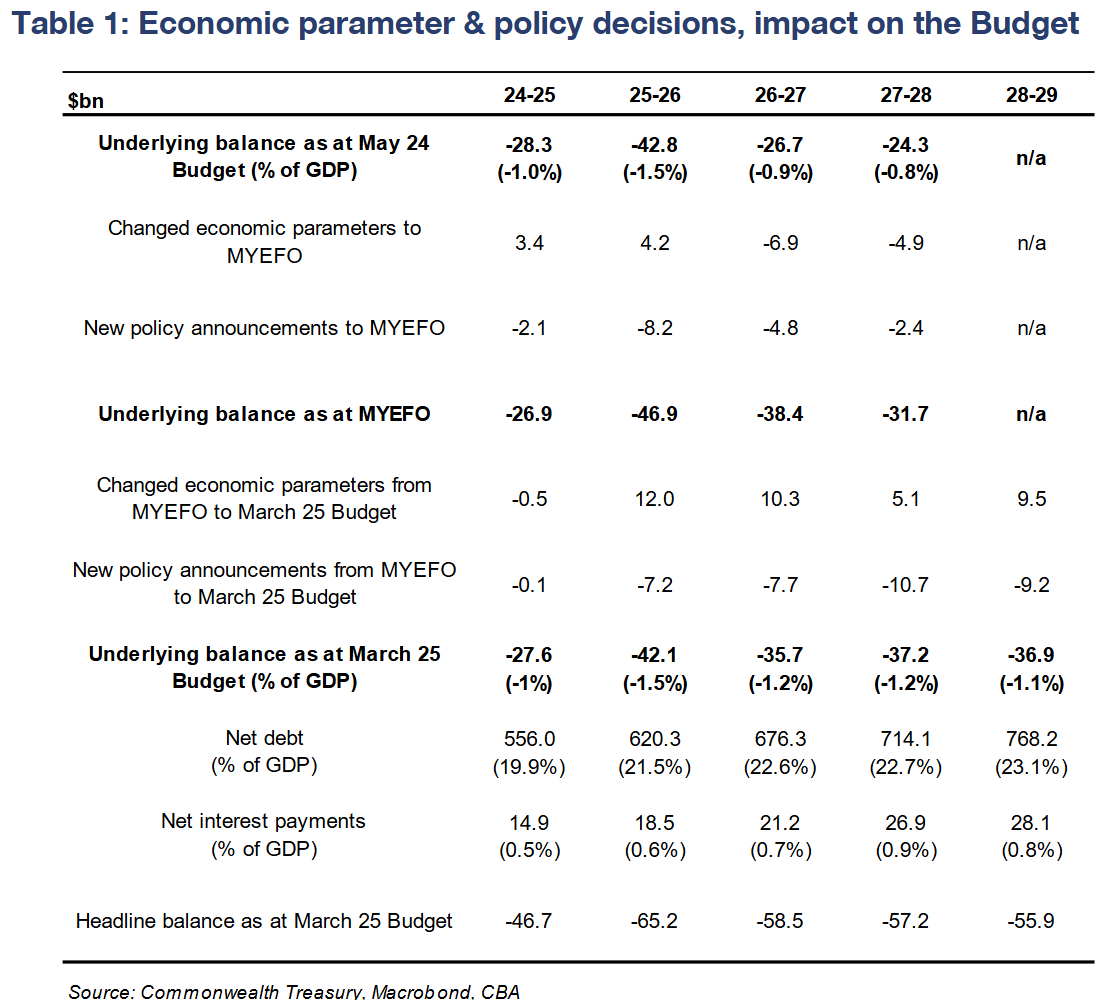

The Budget aggregates change from either active decisions made to policies or from changes to economic parameters (e.g. economic forecasts and changes in existing demand-driven spending programs).

Over the five years of forward estimates contained in the Budget papers, parameter changes have improved the budget position by $36.4bn. $8.4bn of that has been driven by stronger receipts while there has been a reduction in payments by $28.0b. However, active policy changes have reduced the Budget position by $34.9bn.

Framing this another way; the windfall from a stronger economy has been spent and not saved.

The largest parameter changes have come from an upgrade in tax receipts ($9.4bn) due to a stronger labour market(lower unemployment and higher wages).

We believe that wages growth forecasts are too optimistic in the outyears, presenting risks to some of this extra revenue generation.

Near term improvements in commodity price revenue has helped shorter term projections. Other parameter changes have reduced payments. Much of this has been driven by revising estimates lower for NDIS payments ($3.9bn over five years), interest payments ($3.3bn over five years) and slowing the infrastructure pipeline (road and rail transport projects)($4.6bn over five years).

In relation to active policy decisions, tax cuts and increasing the Medicare levy low-income thresholds as well as other minor policy changes reduce receipts. There have been a number of policy decisions that have increased payments. These include improved access to healthcare, infrastructure,new and amended listings on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, energy bill rebates, National Health Reform, cheaper medicines and school funding.

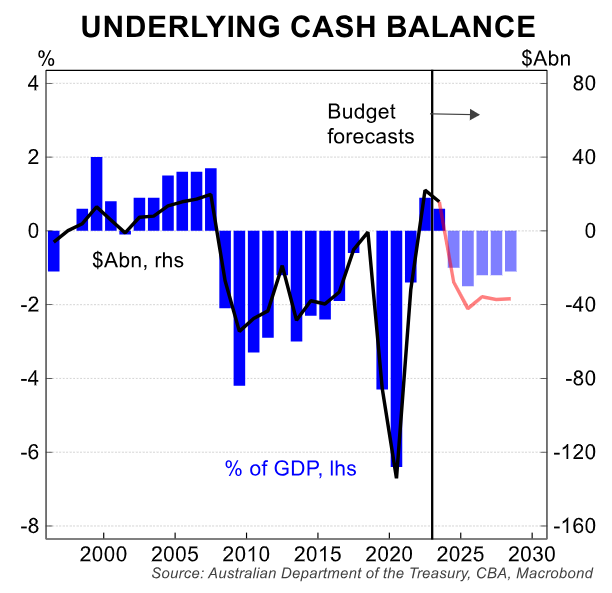

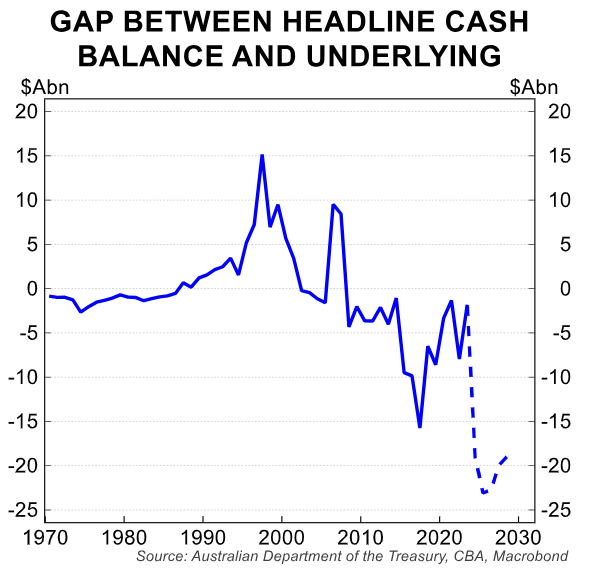

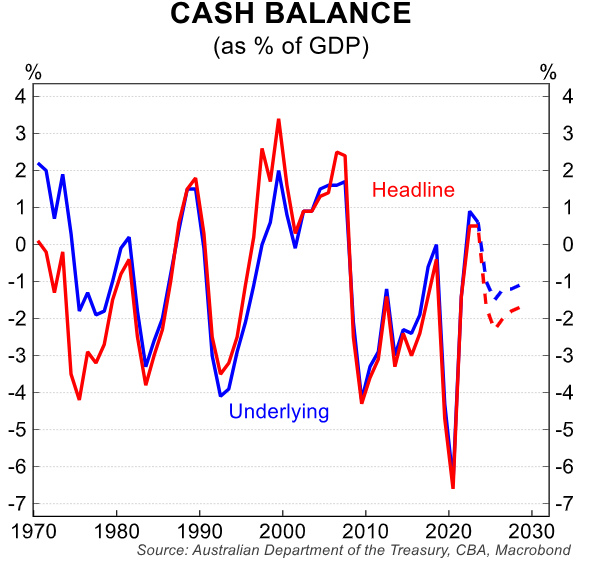

Looking at the numbers in detail, the Budget estimates an underlying deficit of $27.6bn (-1.0% of GDP) for 2024-25. This is a turnaround from the surplus of $15.8bn (0.6% of GDP) in 2023-24, but similar to the $26.9bn forecast in MYEFO and below the May 2024 budget forecast of $28.3bn.

Parameter improvements have improved the deficit by ~$3bn over 2024-25 while policy decisions have worsened the deficit by ~$2bn.

In 2025-26 the Budget estimates an underlying deficit of $42.1bn (-1.5% of GDP). This is an improvement since the MYEFO estimate of $46.9bn and the May 2024 estimate of $42.8bn. But there has been a large degree of movement in the 2025-26 numbers.

Since the May estimate a year ago, parameter variations have improved the deficit by a large $16bn. But policy decisions have largely wiped this parameter improvement out.

As we note above, this is a common theme in this year’s Budget. Over the medium term, the structural budget position continues to deteriorate. And the risk is that additional spending pressure builds, and there is less room for parameter changes to improve the budget bottom line, particularly if nominal outcomes disappoint.

Beyond the next two years budget deficit forecasts remain steady at ~1.2% of GDP, larger than the May 2024 estimates, driven by policy decisions.

As we note above improvements from parameter changes have been spent and not saved. The underlying cash balance is expected to return to balance in 2035-36.

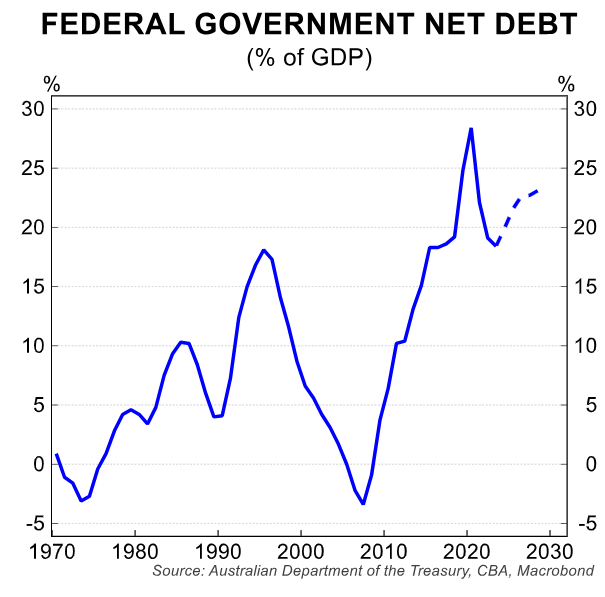

Australia’s fiscal position in the global context

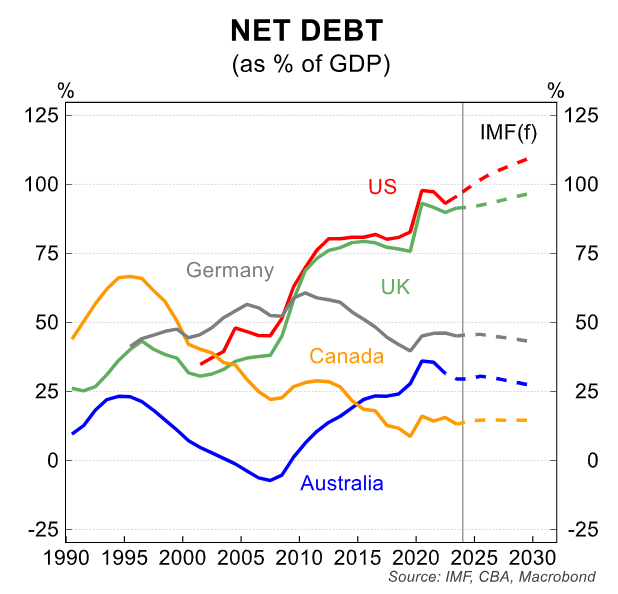

Australia’s general government fiscal position –which includesstate and local governments –is strong relative to many of our peer economies.

The government debt-to-GDP ratio in Australia has increased substantially over the past decade and a half. Government debt levels are well above pre-pandemic levels. But it remains reasonably low compared with most other similar advanced economies.

However, going forward, medium to long-term pressures on spending are expected to rise, especially given expenditure needs in health, disabilityand aged care, defenceand infrastructure.

The sustainability of the fiscal positionwill depend on the revenue side of the budget equation. We believe there is downside risk to the Government’s revenue projections in the outer years given that it is assumedthe unemployment rate holds at 4.25% and wages growth accelerates to 3.75%.