I noted recently how Australia’s housing obsession has gradually choked the economy.

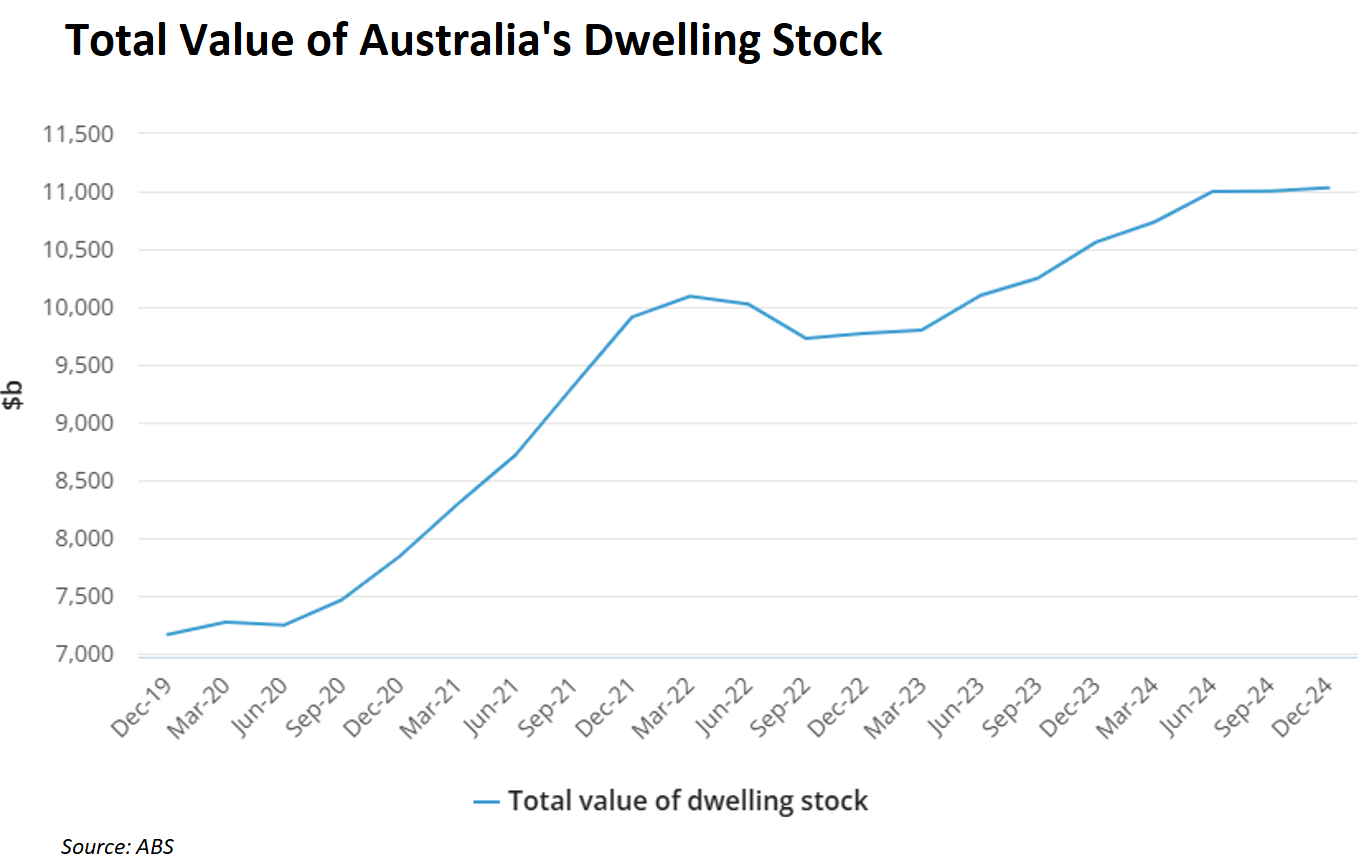

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that Australia’s housing stock was valued at a record $11,032.2 billion in 2024, with the average home valued at $976,800.

According to CoreLogic’s most recent monthly chart pack, Australia’s housing stock was valued at $11.3 trillion as of March 31, 2025, with the average home worth exactly $1 million.

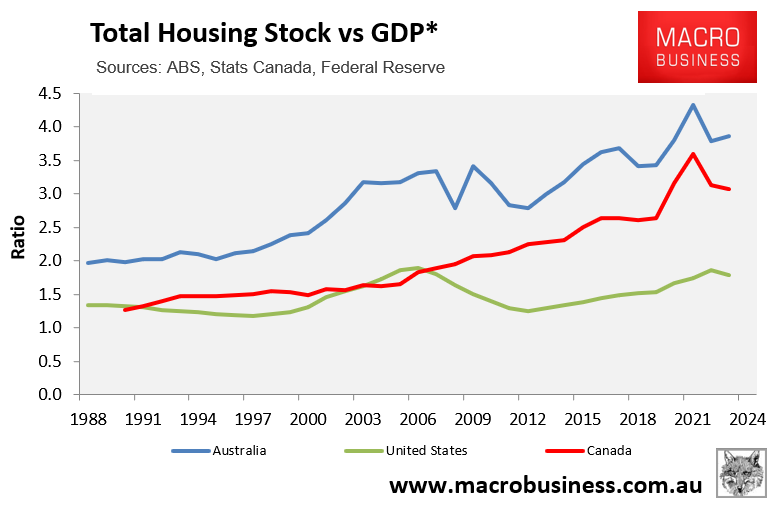

Australia’s property market is worth more than twice that of the US, making it one of the world’s most expensive.

Twitter (X) user Oliver in WA posted some stunning charts comparing Australia’s housing market to its stock market, GDP, and household income.

Oliver found that “Australia doesn’t just have expensive housing; we have an economy built on asset inflation, not productive growth. While the US builds companies, we build property portfolios”.

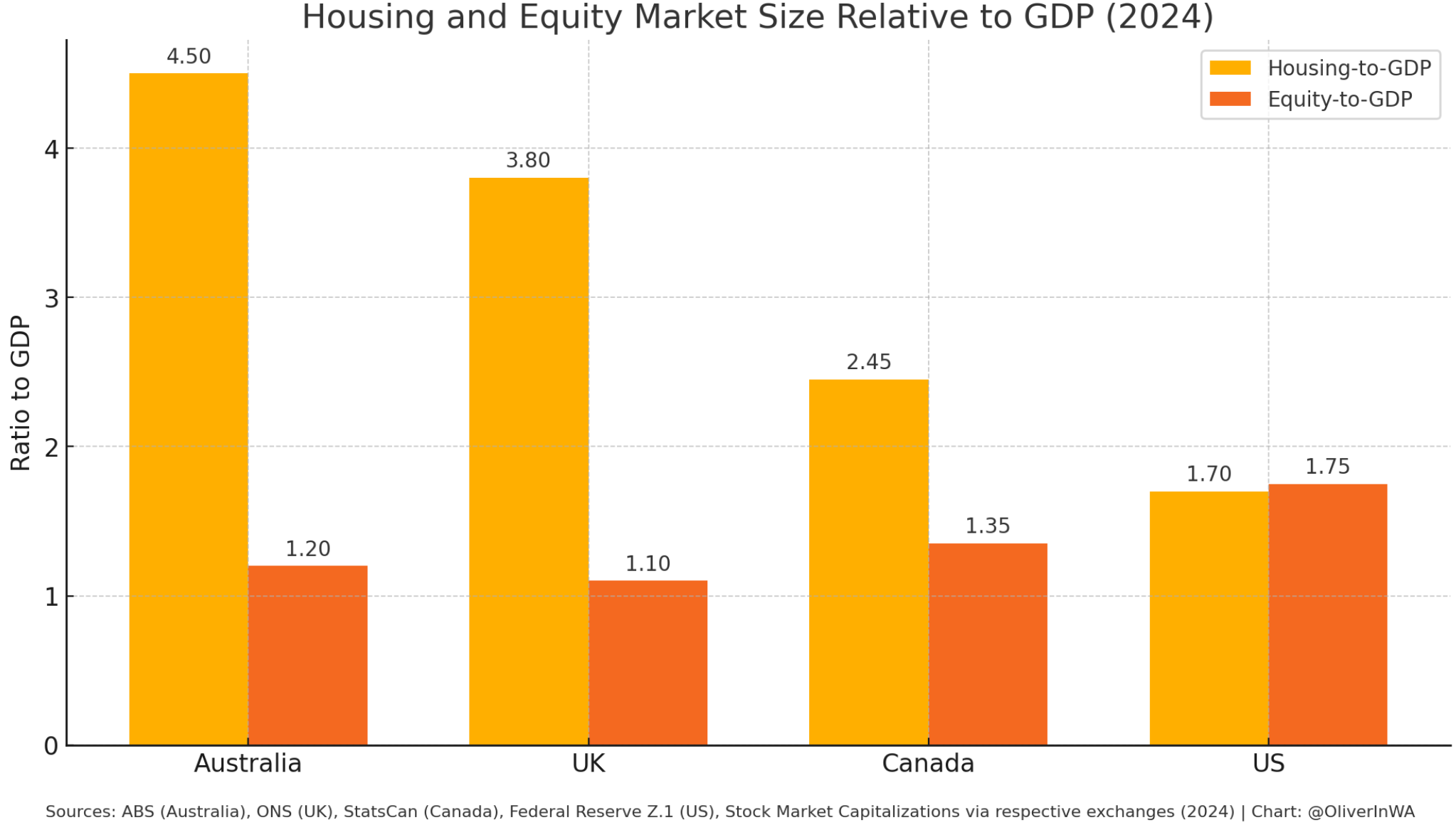

The following chart shows that Australia is heavily overweight in housing (4.5 times GDP) and relatively underweight in equities (1.2 times GDP).

The comparison to the USA is particularly stark, with housing in the US valued at only 1.7 times GDP and equities valued at 1.75 times GDP.

Oliver argues that Australia’s housing obsession has fueled the crisis:

- Capital floods into property speculation.

- Business investment dries up.

- Wages & productivity stagnate, but housing soars.

“Until we rebalance by investing in productive sectors and cutting housing incentives, Australia will stay property-heavy, fragile, and unproductive. Shrinking to an eventual collapse”, Oliver wrote on Twitter (X).

“Wealth trapped in bricks and mortar doesn’t grow an economy”.

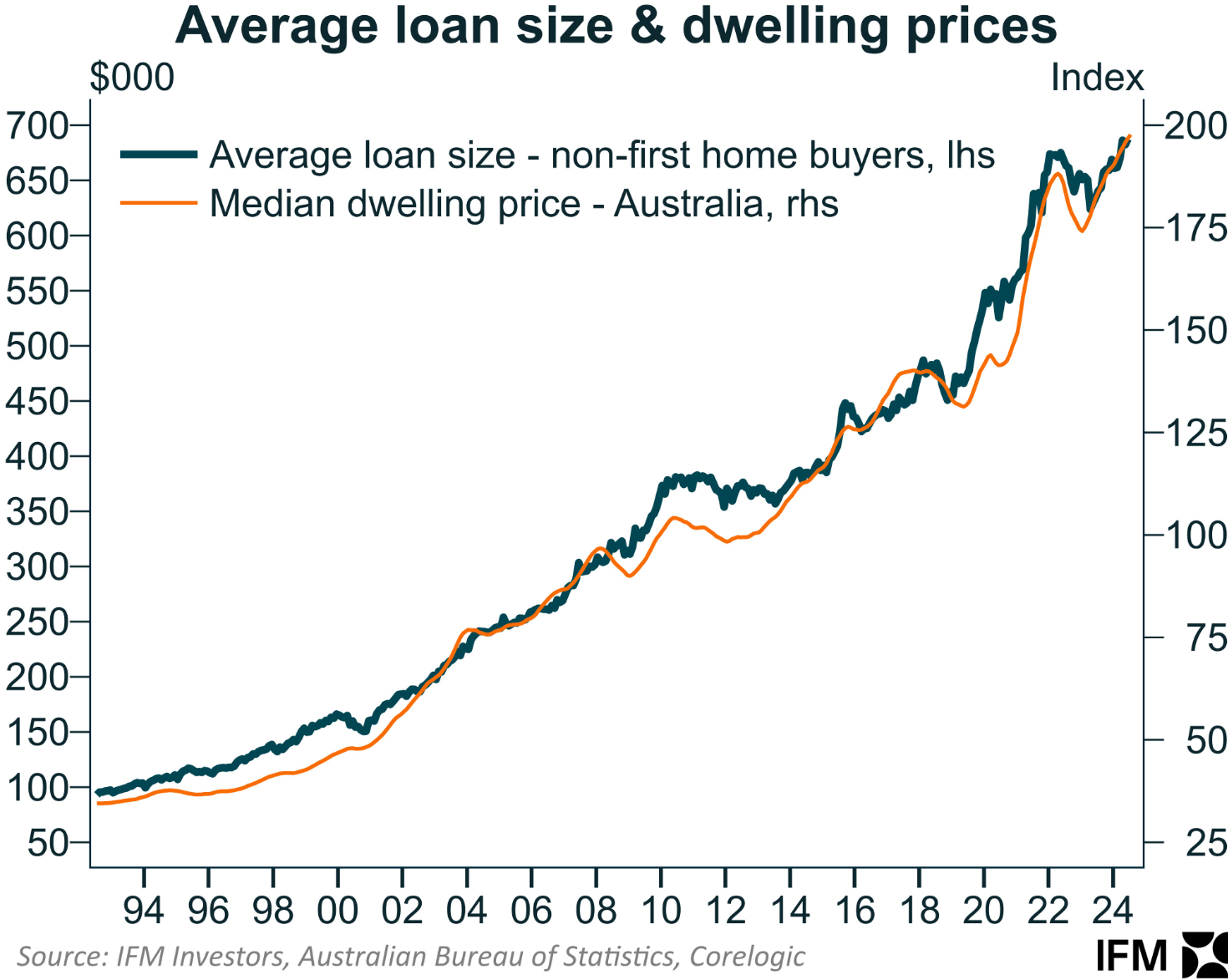

As previously mentioned, rising mortgage debt has driven property values higher.

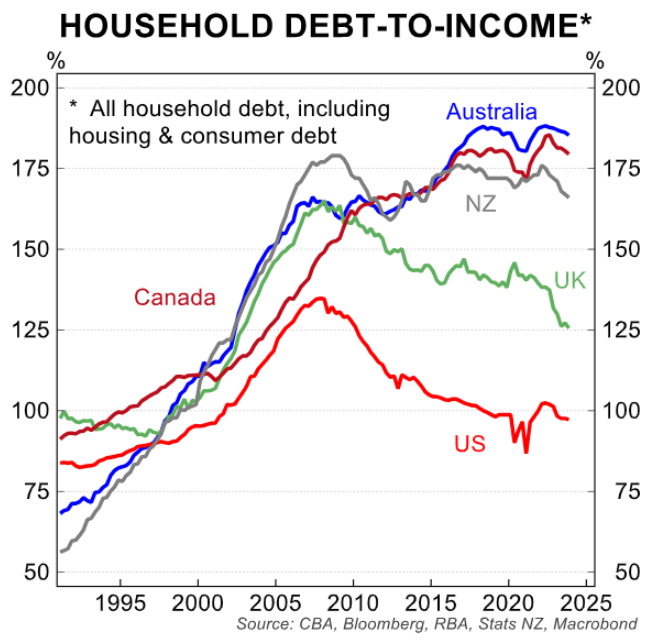

As a result, Australian households carry some of the world’s highest debt loads.

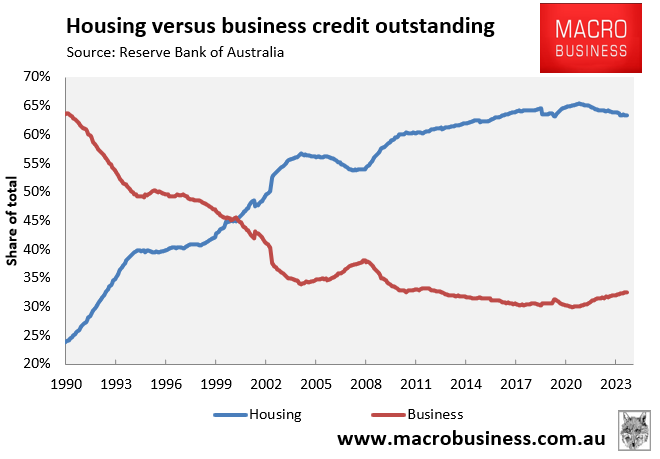

Australia’s banks have evolved into massive building societies focused on home lending at the expense of productive enterprises.

In 1990, roughly two-thirds of bank lending was for businesses, with mortgages accounting for only around a quarter.

Thirty-five years later, the ratio has flipped, with over two-thirds of bank lending for homes and barely one-third for companies.

As explained by AustralianSuper chief executive Paul Schroder at last month’s 2025 AFR Business Summit, the nation’s housing obsession has sucked capital from the productive economy.

“All we’ve done is pour all of this money into houses, which has deprived the economy of heaps and heaps of productive capital”, Schroder said.

“We’ve got all this money in domestic houses and we’re not backing business, we’re not creating new things, we’re not driving productivity”…

“I think the big, burning productivity and cost of living problem is housing. I think we keep underestimating how worrying housing is”.

Sadly, the federal election campaign has seen both sides promise to leverage the federal budget to drive more capital into housing.

Labor’s commitment would effectively create a state-sponsored subprime mortgage scheme by allowing all first-time home buyers to purchase a property with a 5% down payment, with the government (taxpayers) guaranteeing 15% of the borrowers’ loan.

Labor has also stated that mortgage lenders will no longer be required to include student debts in their serviceability assessments.

The Coalition’s announcements are equally inflationary for property prices. These include permitting first-time home buyers to use their super savings as a down payment and making mortgages for new homes tax deductible for first home buyers.

Regardless of which side wins the upcoming election, their policies will significantly enhance borrowing capacity and suck more buyers into the market.

As a result, they will further increase household debt and property prices, as well as divert more of the nation’s capital into non-productive housing.