Money.com has released research suggesting “there could be more pain ahead for renters”.

Money.com points to analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Consumer Price Index (CPI) data showing that rents have risen by 14.2% over the past two years — more than double the overall inflation rate of 6.6%.

This 14.2% increase reflects the compounded rise of 7.3% in 2023, followed by a further 6.4% increase in 2024.

“The last time Australia saw two consecutive years of rent growth above 6% was in 2007–2008, during the height of the GFC”, Money.com.au notes. “Back then, rent growth peaked at 8.4% in 2008, followed by six years of rent inflation outpacing general inflation”.

“Based on current trends, projections show rents could rise another 18% by 2030”.

“There is a growing divide between homeowners who are likely to see another rate cut soon and lower mortgage repayments, and renters who will continue bearing the brunt of the housing crisis”, Money.com.au’s Property Expert, Mansour Soltani, said.

“The last time we saw rent rises like this was during the GFC, and back then, it took years for the market to stabilise”.

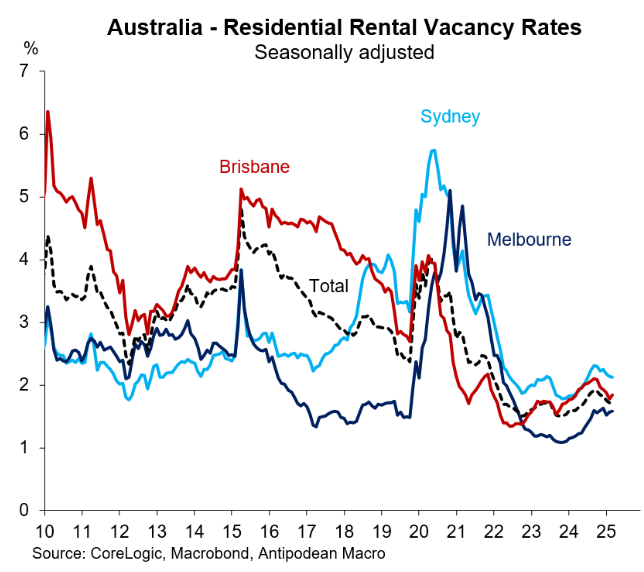

“With population growth, record-low vacancy rates in capital cities, and limited housing supply, it could take even longer this time around”, Soltani, said.

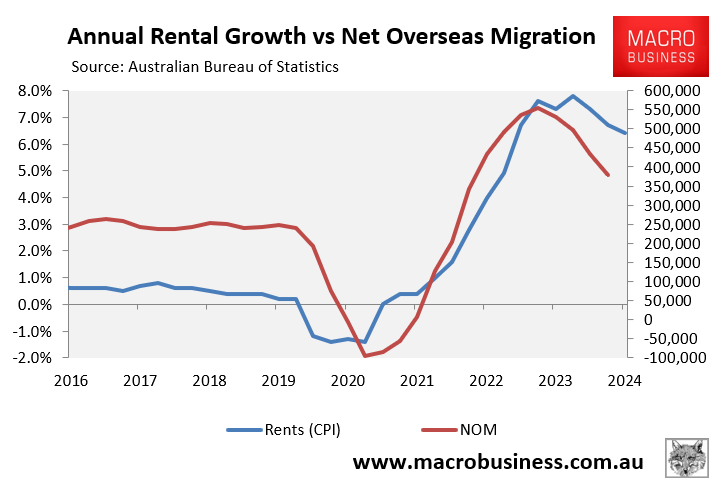

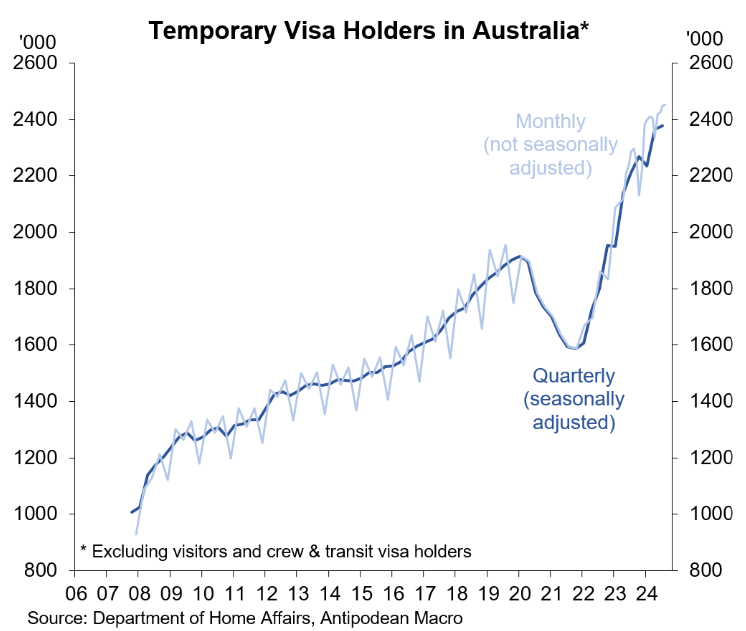

The surge in net overseas migration following the pandemic is behind the decline in the rental vacancy rates and the strong rise in CPI rents.

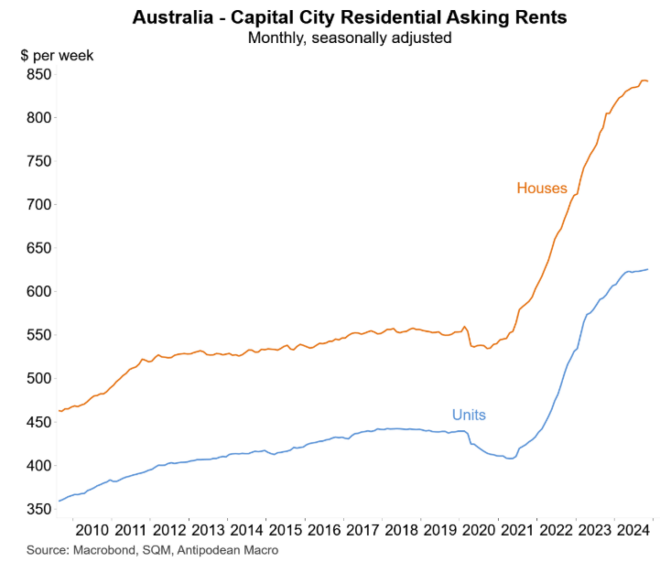

The same can be said about advertised rents, which surged following the record influx of temporary migrants.

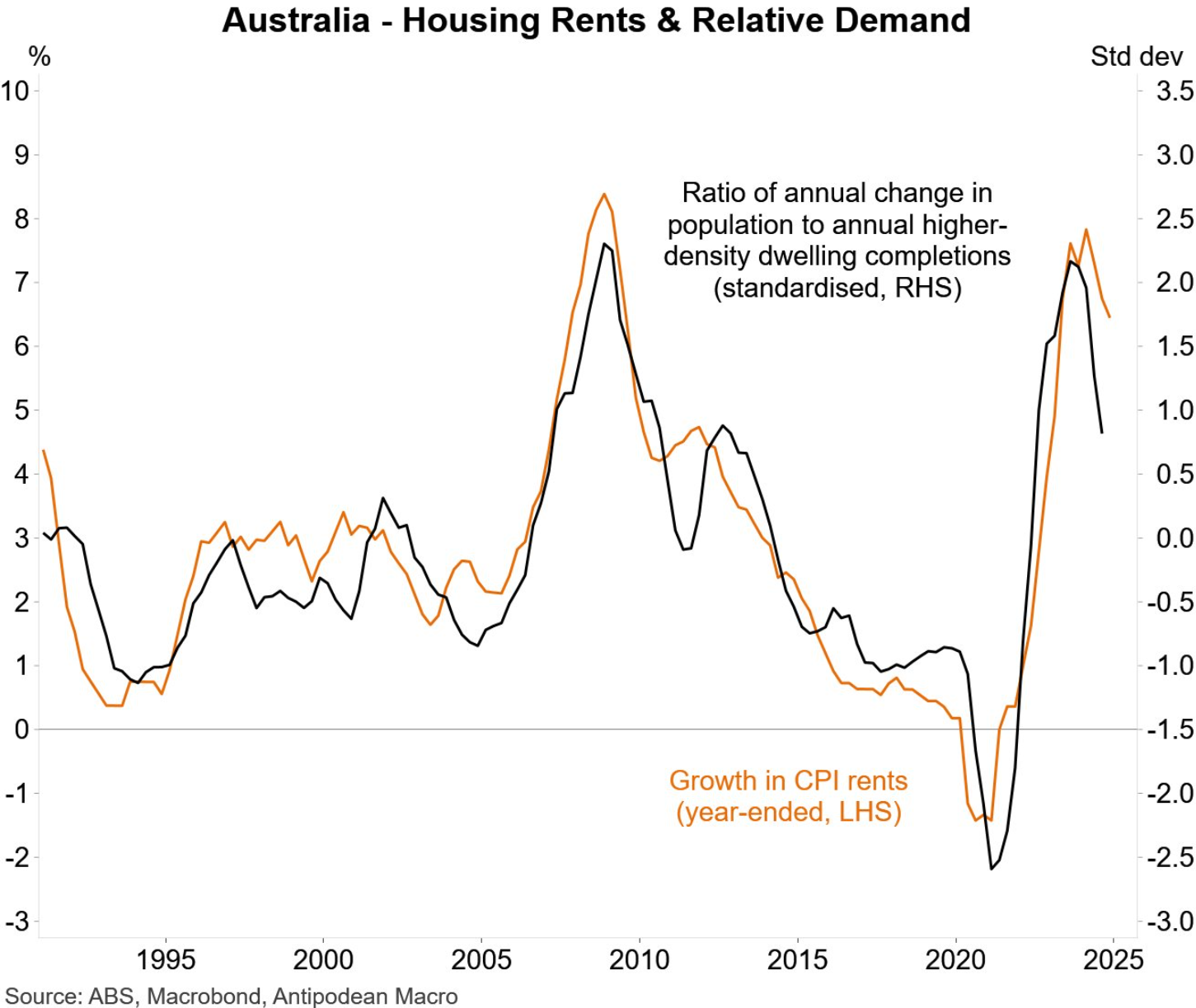

Ultimately, whether rents continue to rise at a strong pace will depend on the strength of net overseas migration relative to dwelling construction.

This is illustrated clearly in the following chart from Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro, which plots the clear relationship between housing demand/supply and rents.

If net overseas migration remains strong, then there will be upward pressure on rents. However, if migration is cut, then rental inflation will ease.

The level of apartment construction also matters to this equation. However, most economists and property analysts expect the supply side to remain bottlenecked for the foreseeable future.

The bottom line is that if policymakers genuinely want to ‘solve’ the rental crisis, then net overseas migration must be cut hard.

Doing so would also assist first home buyers via two channels:

- They would be able to save a deposit faster because they would spend less on rent.

- Lower immigration would also place downward pressure on home prices, making the purchase price more affordable.

Continuing to import hundreds of thousands of people into the housing market every year is highly detrimental to affordability and livability.