Albert Edwards of Societe Generale famously coined the phrase “Ice Age” for the period leading up to and after the GFC. The Ice Age thesis was based on the notion that immensely deflationary forces would emanate from a balance sheet recession taking hold in developed economies.

Now Edwards sees the same coming from and for China.

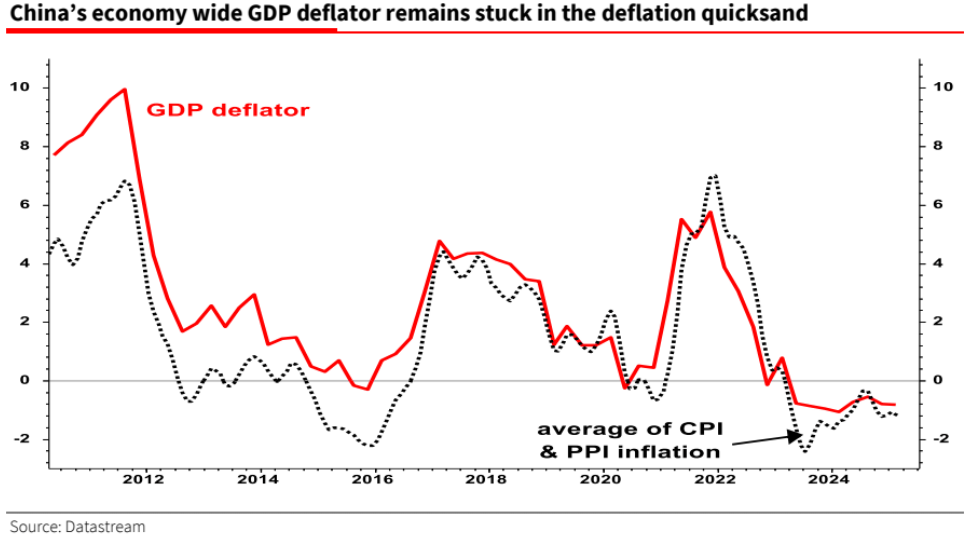

Whenever Chinese GDP data is published, I always make a point of checking out what the deflator is doing.

This measure of inflation is the broadest economy-wide metric available and goes beyond CPI and PPI.

Despite China’s latest data-dump showing some economic recovery fuelled by stimulus measures, it also signals a slight worsening in deflation pressures.

Our China economist Wei Yao describes the higher-than-expected 5.4%yoy rise in Q1 real GDP as “solid”.

Together with the avalanche of other data, this suggests that stimulus measures have led to improvements in retail spending and the housing market among other things.

But as she notes, this is before the impact of US tariffs hit home.

So what caught my eye among the deluge of China data is that the GDP deflator continued to decline, falling 0.8% yoy in Q1-slightly lower than the Q4 figure(see chart below).

We had a heads up that China’s GDP deflation may have worsened in Q1, as the average of CPI and PPI (a reasonable proxy) had already slid lower (see chart below).

The Chinese economy has been trapped in deflation for two years now, and with a tsunami of US tariffs hitting imminently, it is unlikely to exit deflationany time soon.

Surplus capacity in the manufacturing sector will be desperately thrashing around for markets like a beached whale.

The experience of Japan is once you slide into deflation it is extremely difficult to escape as economic agents’ expectations adapt to the new reality.

If the economy doesn’t hit escape velocity quickly, then the deflation quicksand sucks you down lower and lower.

Poor Chinese demographics, like Japan, makes the quagmire even more difficult to escape.

China also has an extraordinarily poor fiscal position. Don’t take my word for it; the normally timid IMF has singled out China’s fiscal situation as unsustainable.

Indeed it’s even worse than the US, if that can even be imagined.

When any economy with high debt loads slides into deflation, it is a highly toxic combination that should be ringing very loud alarm bells.

And this is the case even before the impact of the potentially mind-boggling tariffs.

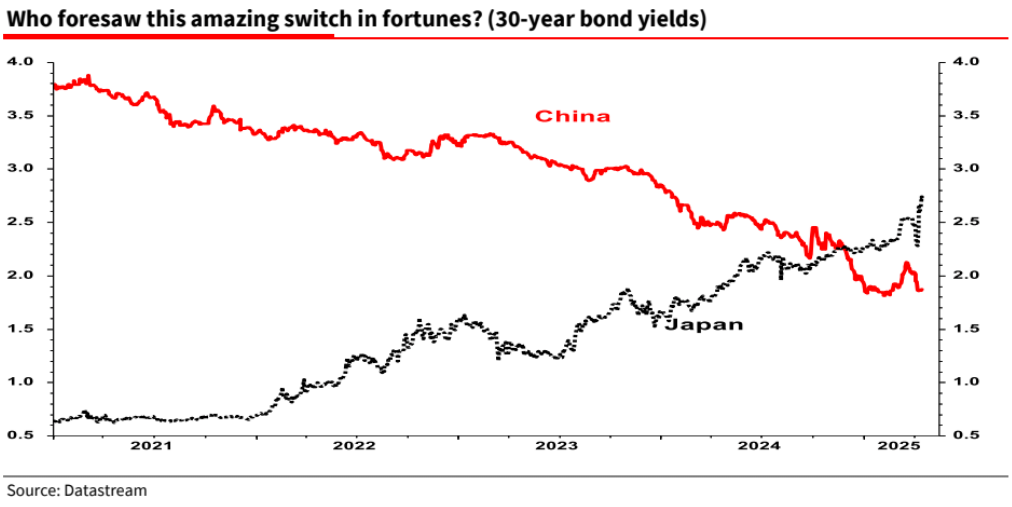

Personally, I am simply amazed investors are so sanguine–although the Chinese bond market at least seems to understand the magnitude of the unfolding economic crisis.

The Chinese bond market certainly seems to have understood the deflation trap the economy has fallen into with President Trump’s tariff measures fully reversing the recent rise in yields.

But believe it or not there is a silver lining to China’s problems for US bond investors.

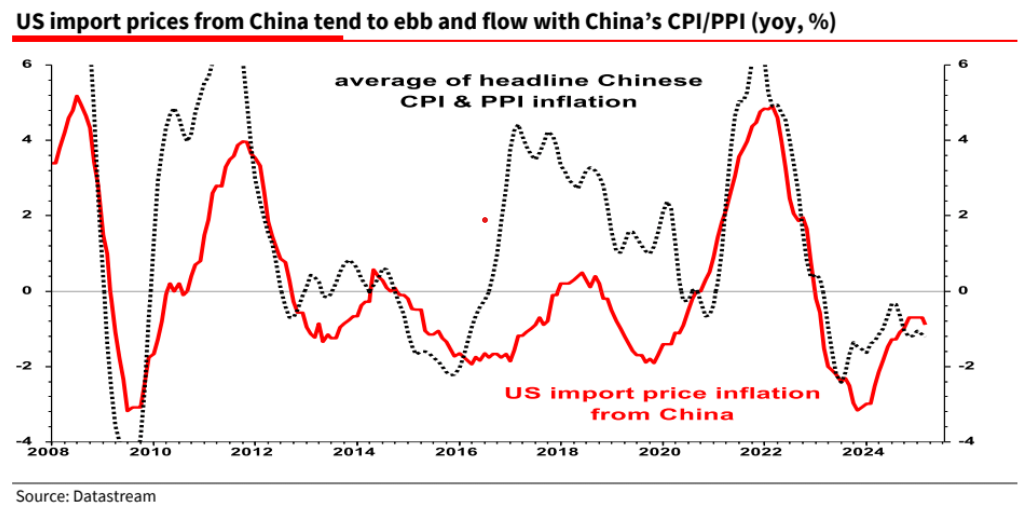

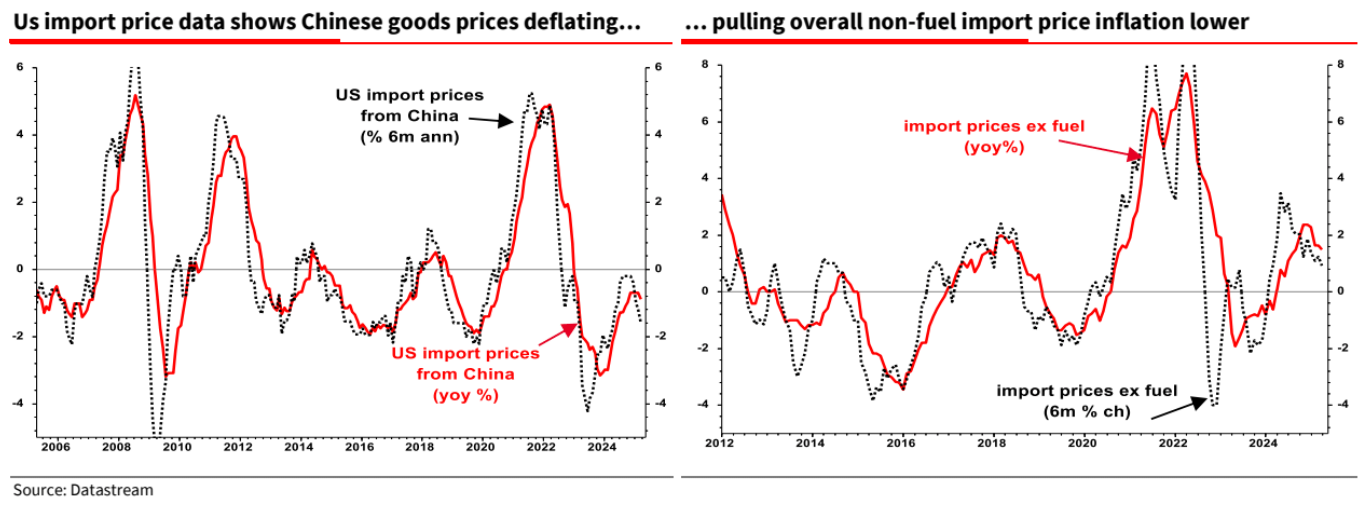

Even before the tariff wars, the price of US imports from China was slipping into deeper deflation–in line with PPI/CPI.

The down tick in the red yoy line above shows import price deflation from China starting to deepen again (this is more noticeable on a 6 month basis, see left chart below), pulling down overall import price inflation back towards zero (right hand chart).

We highlighted last week that the super-strong trade weighted dollar is currently exerting strong downward pressure on US inflation–hence it is no surprise that the latest US core CPI and PCE data dramatically undershot expectations.

The $64,000 question is the near-term outlook for inflation.

Our impression is that almost every commentator expects US tariffs to exert a strong upward pressure on US inflation, at a time when they also expect the economy to slide into recession.

But what if they are wrong and US inflation unexpectedly falls?

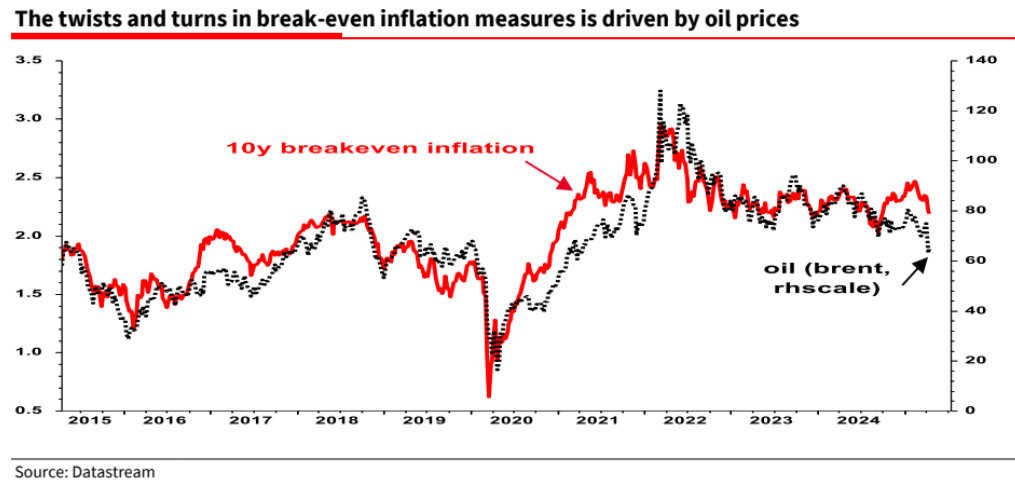

Certainly,10y break-evens are now beginning to move lower in line with oil prices.

Another ‘surprise’ source of deflation could be the degree to which US companies are willing or forced to ‘eat’ higher tariff-related costs.

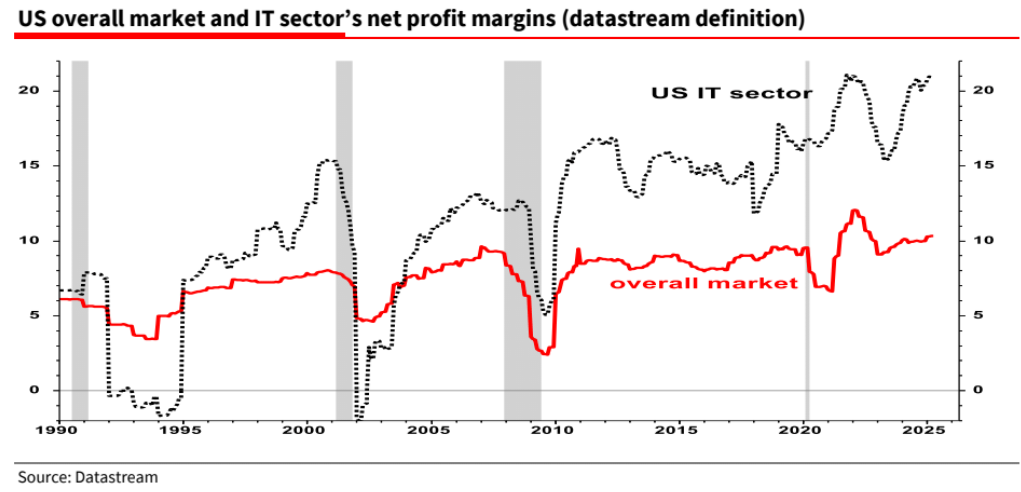

For example, when Iread panicky headlines that tariffs may massively push up the price of tablets and phones, I note the record-high margins in the US IT sector (Apple at 47% for example).

There is certainly plenty of ‘fat’ to cut into.

It is worth repeating what I said last week about President Trump using the FTC to prevent US companies passing on tariff increases.

It seems obvious to me that he would do that.

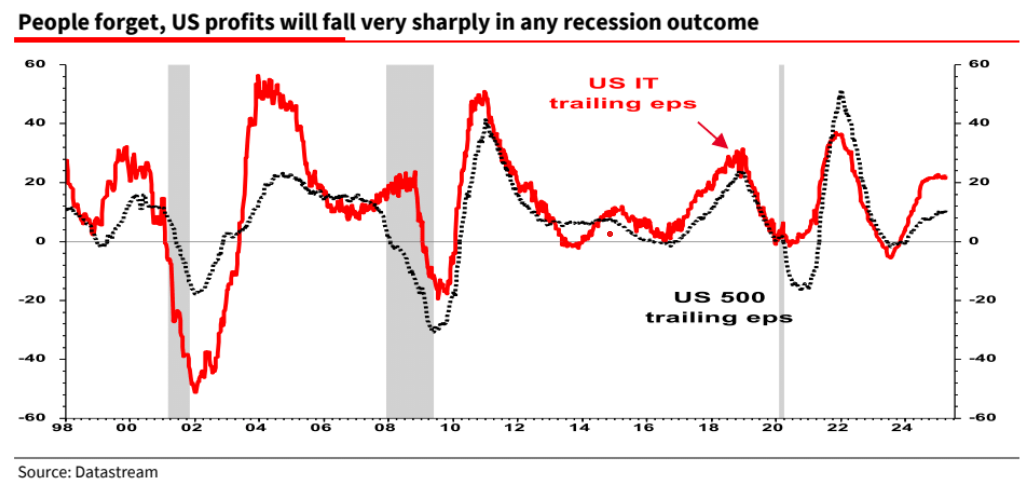

So tariffs may prove much worse for stocks than bonds if, as seems likely, a recession now unfolds.

The only riposte I would make for the short term is the prospect of the baby president spitting his dummy at the Federal Reserve.

Suppose the baby president removes Jay Powell in a new tantrum, which seems dangerously probable because the baby president must always have the attention, even when it damages his agenda.

In that case, US capital outflow will accelerate as institutional trust in US assets takes another body blow, and the long bond will sell off even further.

I agree with a lot that Albert says, in particular that a deflationary tsunami is about to sweep the global economy and Australia in particular.

The problem is in how to play it.

The baby president isn’t playing four-dimensional chess. He’s chucking daily tantrums to hold the world’s attention in a fruitless attempt to fill the bottomless pit of an absent soul.

Hence, there is every chance that terrible implementation will be all that matters to an agenda that has some merit.

I am in cash (not bonds) until such a time that the baby president is either sufficiently restrained or his attention is drawn to some other plaything than the demolition of the Bretton Woods II world order.