Last month, Vicki Thomson, the CEO of the elite Group of Eight (Go8) universities, claimed that international education is the nation’s third-largest export.

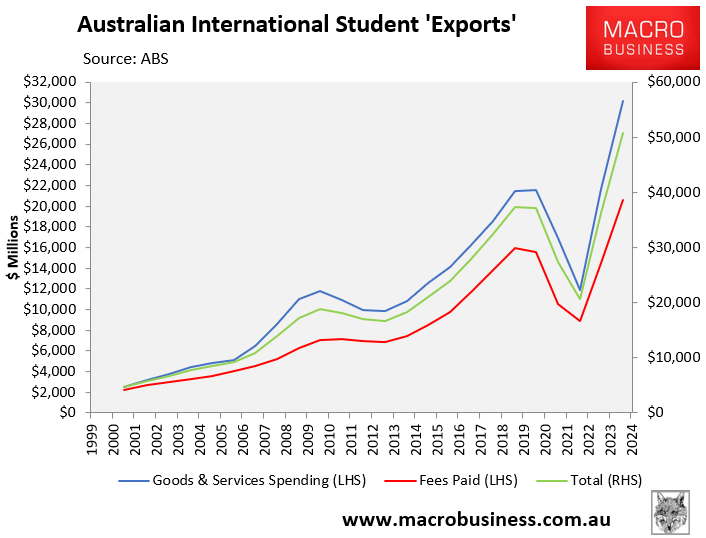

Amid talk of imposing caps on enrolment numbers, Thomson said, “Do not put our third-largest export sector at risk. A $51 billion economy and, more than that, a sector which actually builds our skills base [and] does not damage the economy but enhances the economy”.

“Do not put that at risk for cheap political point scoring”, she said.

Thomson’s claim was demonstrably false. Even the Department of Education states that education was Australia’s fourth-largest export, worth $51 billion last financial year.

However, the official $51 billion figure from the ABS is wildly overstated since it: 1) counts all expenditures by international students as an export, even when the money is earned in Australia, and 2) ignores money sent home by students as remittances.

Higher education expert Andrew Norton made these points in an article that appeared in The AFR last week:

“The reality is that for people from poor countries, even doing unskilled work in Australia, is going to pay more than what they would earn back home”, Norton said.

“And if they’ve borrowed money to finance their university or vocational course, which many will have, being able to work in Australia is an important part of paying the cost of that back”.

Presumably, most of the money students borrow will be from families in their home countries. Therefore, the repayment of these loans effectively eliminates the export component of international education.

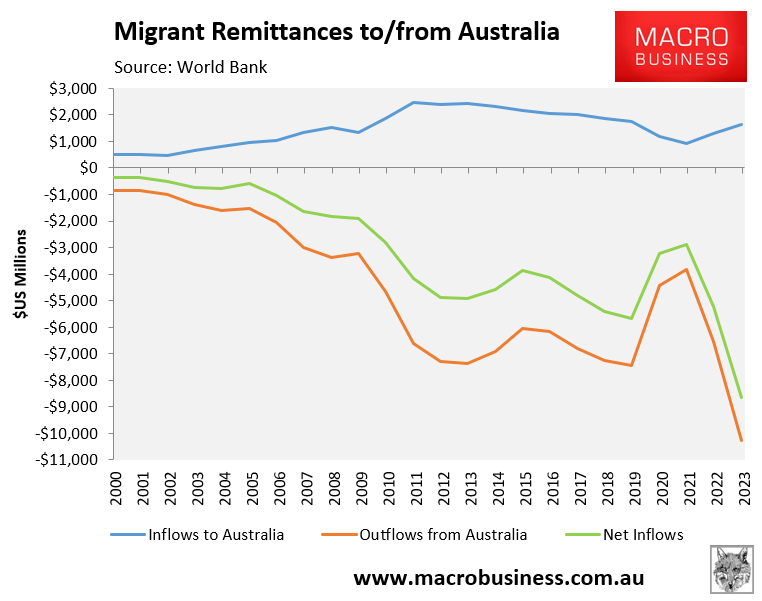

Indeed, Australia loses significant sums of money abroad via remittance payments.

According to the World Bank, Australia sent US$8.6 billion in net remittances to other nations in 2023. A significant share of these remittance outflows would have originated from students working in Australia and sending money home.

However, these remittance outflows are excluded entirely from the ABS’ fantastical education export figure.

In a similar vein, the ABS last year admitted that one-quarter of the reported education export figure comprises money earned in Australia and, therefore, is not an export:

All expenditure by international students studying in Australia is recorded as an export in the Balance of Payments statistics published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This includes expenditure on tuition fees, food, accommodation, local transport, health services, etc., by international students while in Australia. This expenditure contributed $50.5 billion to Australia’s exports in the 2023-24 financial year.

The classification as an export of expenditure by international students studying in Australia does not depend on how the students fund their expenditure in Australia. Some of the expenditure is funded from overseas sources. While it is not possible to be precise, ABS estimates suggest around a quarter of the expenditure (around $13 billion in the 2023-24 financial year) is funded by international students working in Australia for Australian employers.

The ABS said it won’t change how it reports education exports because it is an international standard.

A significant share of students work off-the-books for cash. Therefore, the true income students earn in Australia would be higher (meaning education exports are lower).

Therefore, it is likely that the ABS’s estimate that one-quarter of expenditure by international students is earned in Australia is highly conservative.

The government, media, and industry should cease reporting the fantastical $50.5 billion education export figure as fact. It is highly exaggerated and misleading.

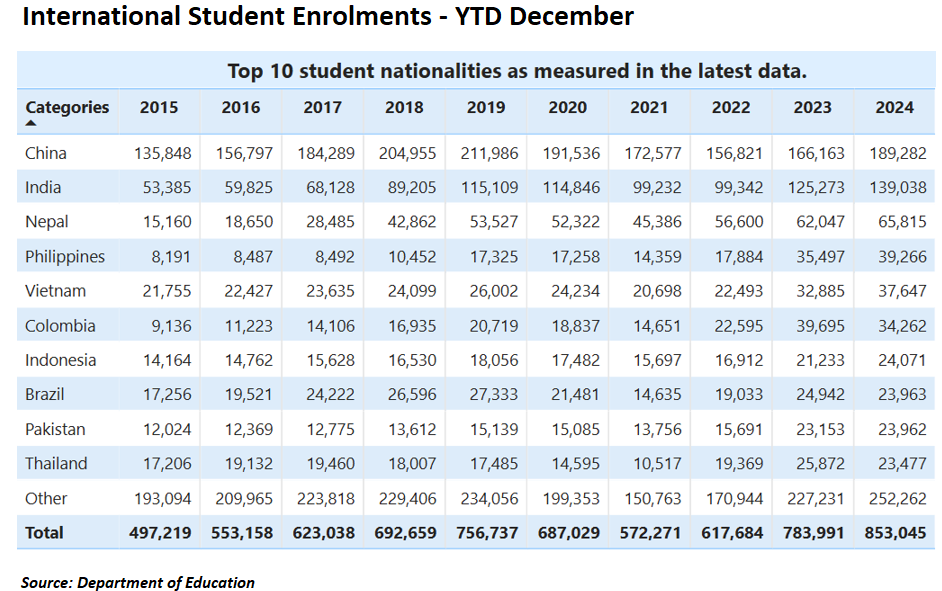

South Asia, led by India, has driven the recent growth in international enrolments.

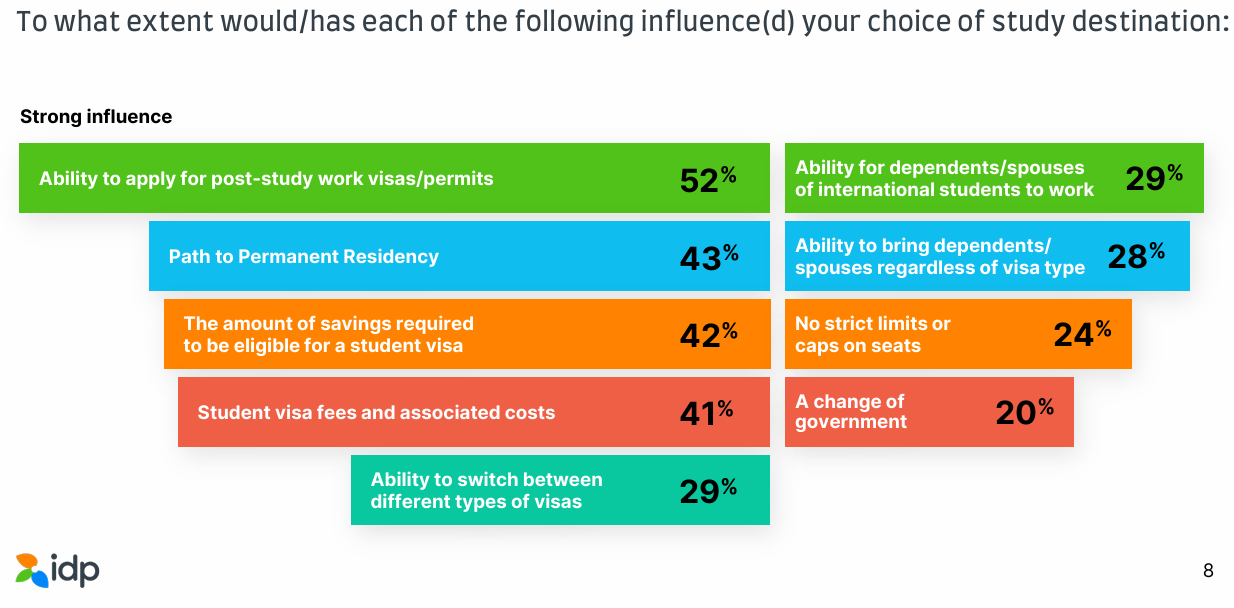

Various surveys indicate that South Asian students prioritise work rights and migration above everything else.

South Asian students care about immigration, not education quality.

Indeed, the most recent IDP Emerging Futures survey indicated that post-study work opportunities (52%) are the most important consideration for international students when choosing a study destination. Pathways to permanent residency rank second at 43%.

Prospective international students also covet the ability to bring their spouses to work and live, which has been ruthlessly exploited by South Asian students and graduates.

Who honestly believes these students from South Asia bring large sums of money to study in Australia?

The reality is that most arrive in Australia with limited funds and take up jobs to fund themselves and send money back home to their families.

Money sent home is by definition an import, not an export.