In the report below, Luke Yeaman, Chief Economist at CBA, examines whether the era of globalisation over.

Trump, Tariffs and Trade: A Different Kind of Wall

- The era of trade liberalisation, free market reforms, deregulation and fiscal discipline (the Washington Consensus) is officially dead and buried. In a few weeks, President Trump has reversed a century’s worth of US trade liberalisation.

- The US administration is committed to its tariff plan and won’t be easily deterred by economic and political pain. This is a long-term project, not merely a negotiating play, so expect a protracted trade war. Tariff rates could yetgo higher.

- Global and US growth will be lower in 2025. Persistent stagflation looks unlikely but can’t be ruled out entirely. It will take a lot to de-anchor inflation expectations and weaker economic growth will suppress broader pricepressures. This means the Federal Reserve should retain the flexibility to cut the Funds rates to support activity as growth slows.

- Australia is relatively well-placed to weather the storm, but we won’t be unaffected. Our fundamentals are sound, and our direct trade exposure is small. A protracted trade war will hurt China and Asia, with flow on effects to Australia. A lot rests on potential Chinese Government policy responses. A large infrastructure-based stimulus, could provide a buffer.

Settle in: We face a new global reality

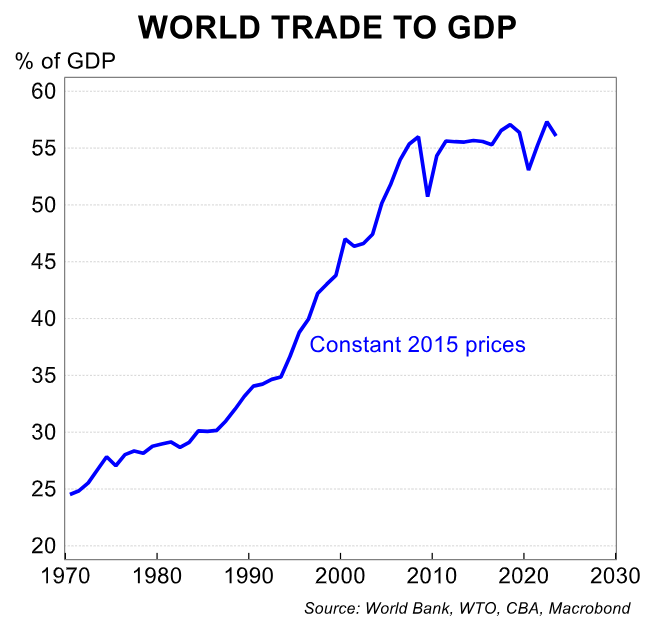

Globalisation has stalled or been in reverse for several years.

A more contested geopolitical landscape and a breakdown in trust between key countries has seen ‘strategic decoupling’ take hold. Around the world, new trade restrictions, regulations and subsidies have been deployed to secure critical supply chains and rebuild domestic industrial capacity.

At the same time, countries are using those same regulatory and fiscal tools to aggressively fight for a share of the emerging industries that come with a new green and digital economy, hoping to gain a ‘first-mover advantage’.

President Trump’s tariff salvo has thrown that process of de-globalisation and re-regulation into overdrive, fundamentally re-shaping the global economic landscape for at least the next decade.

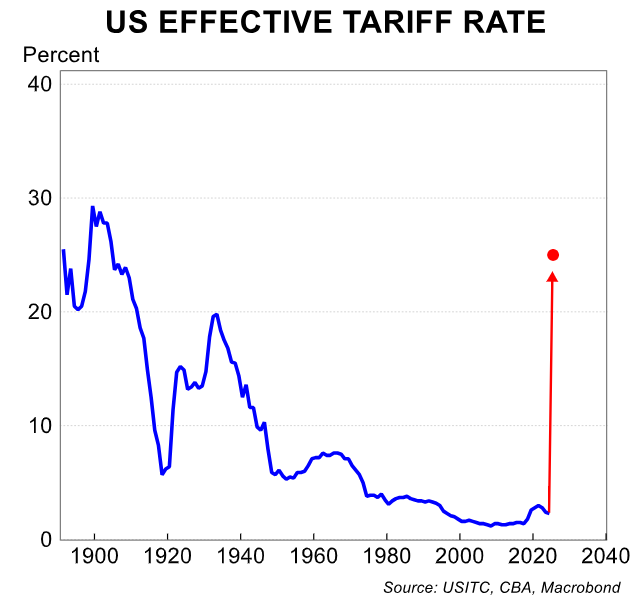

In his first term, the President built a border wall. In this term, he has built a tariff wall. In a matter of weeks, he has reversed a century’s worth of US trade liberalisation and abandoned US leadership on free trade.

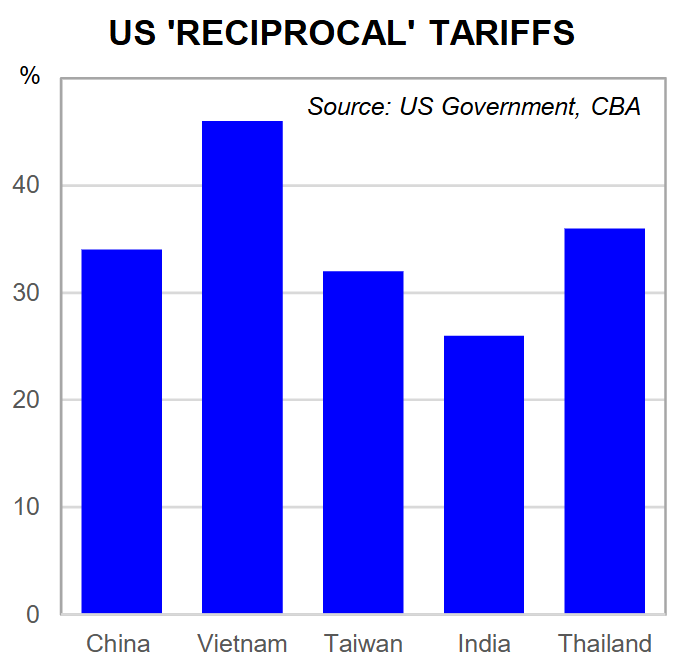

The initial announcements saw average US tariff rate jump from 3% to around 25%; levels not seen since the early 1900s. Average US tariff rates haven’t exceeded 10% since the early 1940s; now all countries face a 10% minimum tariff and many face far higher ‘reciprocal rates’.

The tariff wall is both high and wide. Reversing this trend and dismantling this new tariff wall won’t be easy. Trade barriers are always easier to erect, than dismantle.

A major short-term reversal on US tariff policy would require one of two things. The first is for key target countries to ‘bend the knee’ and offer major trade and other concessions to the US.

While there will be active negotiations—Japan is a case in point—widespread concessions that see average US tariff rates settle significantly lower appear unlikely. Europe, China, and Canada are mostly in ‘retaliation mode’ and they all have important domestic interests to protect.

The second is strong public discontent in the US, most likely in response to a sharply weakening US economy, lower asset prices and higher inflation. This pressure will build as the economy slows and prices rise.

However, the President is clearly prepared to accept short-term political pain to achieve his longer-term goals. An about face can’t be ruled out, but we are unlikely to see any serious retreat, at least until the mid-terms in late 2026.

Method or madness… or both?

As with most of the President’s actions, his tariff plan includes both method and some madness.

We think there are four reasons why the President has taken such an extreme step. Taken together, they explain why he pushed ahead with his plan, despite the inevitable economic pain that would follow. They also provide insights into the future path of this trade war.

Negotiation is the first reason. By applying a severe broad-based tariff and simultaneously holding out the possibility of higher rates or exemptions, Trump has given himself leverage across a huge sphere of US interests.

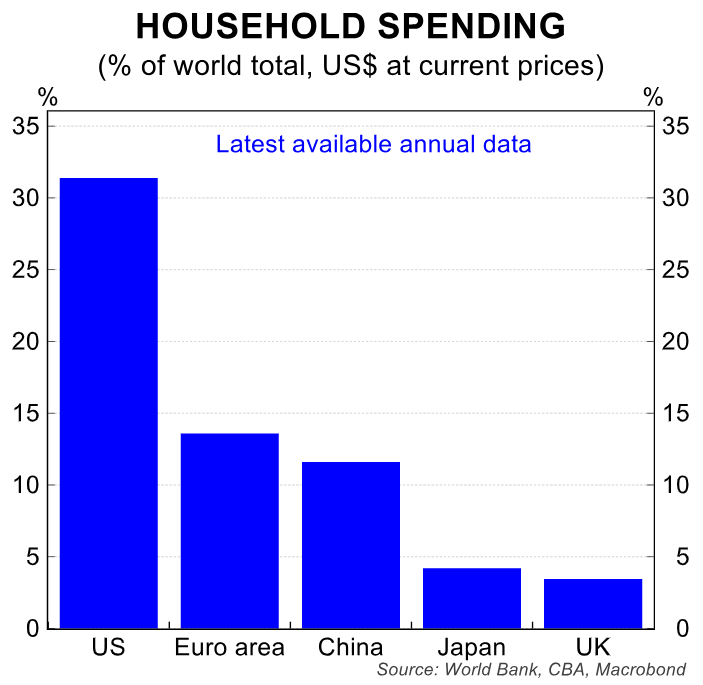

To achieve real leverage, you first need something of significant value and a means to withhold it. In this case, the President is using the US consumer market and tariffs as his main bargaining chip to achieve other goals.

The US consumer remains the single largest engine of global growth and a vitally important market for foreign companies. The US consumer accounts for over a quarter of all global consumer spending. No one else can match this. Tariffs are a way to restrict access to this market or grant one party a commercial advantage over others (albeit at great cost to the US).

Negotiations will be in full swing in Washington as countries all scramble to put offers to the US in the hope of gaining exemptions or, at the minimum, limiting their tariff rates relative to other competitors. These negotiations will be taking place across a range of topics from border control to defence spending and other sector-by-sector US irritants.

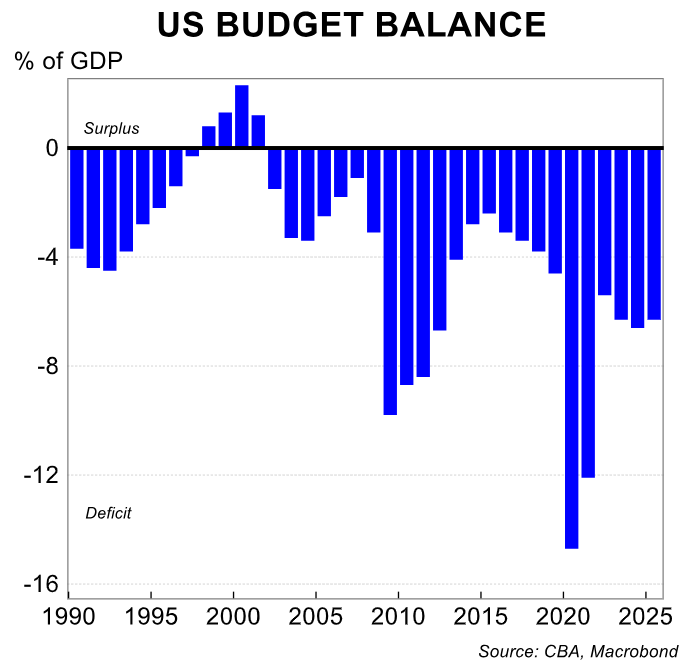

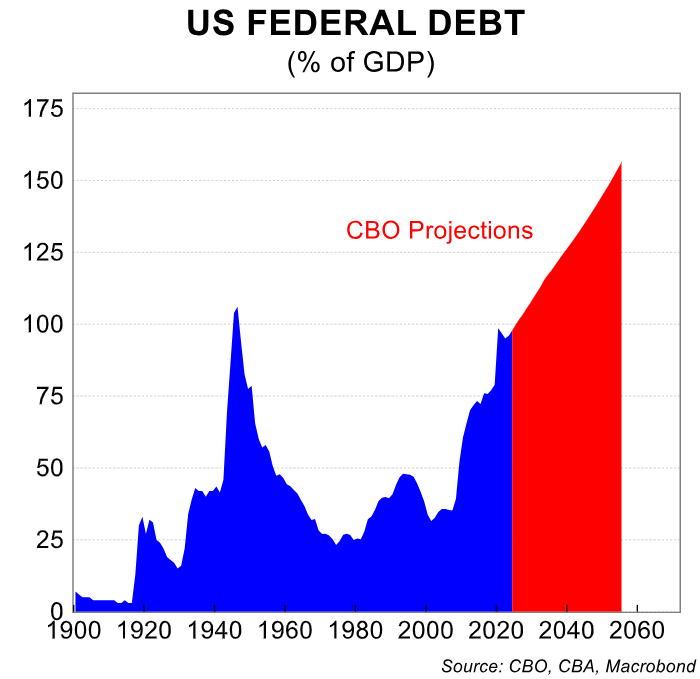

Revenue is the second reason. The US has a huge fiscal challenge. They are running a budget deficit of around $US1.8 trillion or 6.4% of GDP and that is with a relatively strong economy.

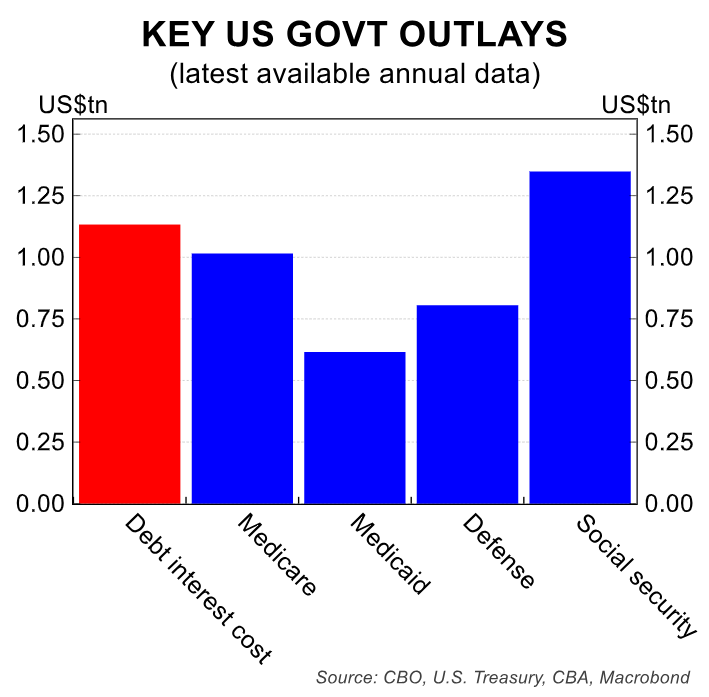

Federal debt is projected to grow rapidly and debt servicing costs already rival spending on major programs such as Medicare, Medicaid and Defence.

US Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, is pledging to contain the yields on 10-year Treasury notes, in part to restrict these debt servicing costs. But this won’t be easy and bond markets are growing increasingly sceptical.

A President has limited options to deliver meaningful increases in revenue or spending cuts without running the gauntlet of the Congress. Successive US administrations have struggled to deliver major spending cuts and the much-vaunted DOGE cuts are mostly symbolic and won’t ‘shift the dial’.

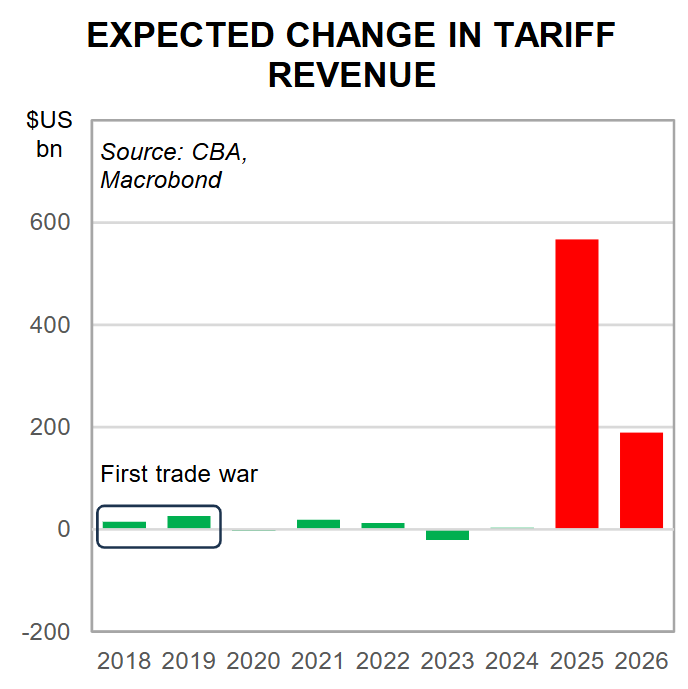

Tariffs are a notable exception. On our estimates, the tariffs could generate revenue of around $US773bn per year or around 3% of GDP if there is no import substitution. This is an upper bound.

If the President succeeds in narrowing the trade deficit, revenue willfall. And the President’s use of ‘national emergency’ powers to impose his tariffs will inevitably face legal challenge. Nevertheless, tariffs are a relatively simple way to collect more revenue to improve the deficit or fund new spending commitments.

National Security is the third reason. The US has urgent strategic objectives to onshore and rebuild industrial capacity in sectors deemed critical to national security. These objectives pre-date the Trump Administration.

A wave of new regulation and investment incentives havebeen rolled out over recent years, most notably the CHIPS Act, to kickstart this de-risking process. However, it takes time to remake complex supply chains and commercial factors still drive supply chains towards lowest cost providers.

In his Liberation Day remarks, the President said “in short, chronic trade deficits are no longer merely an economic problem. They’re a national emergency that threatens our security and our very way of life”. The Trump Administration sees tariffs as another tool in the toolkit to reduce this strategic dependence more quickly.

The plan to Make America Great Again is the fourth reason. This represents straight-forward populism and nationalism; forever the best friends of tariffs and protectionism.

The President promised his base that he would bring back “rust-belt”jobs for prime age males and get a “fairer-deal” for the US in global trade. Liberation day was his way of delivering on that promise.

At a deeper level, there is a strongly-held view in the Trump Administration that the benefits of open trade (i.e. cheap consumer goods and business inputs) have come at too great a cost to US industries, jobs and security. While this is no easy task, they are determined to use this opportunity to rebalance that equation and are prepared to pay an economic price.

What does this mean for the Trade War?

All these reasons have been canvassed by analysts. However, in our view most have placed too much emphasis on the first reason, negotiation. If tariffs were just a negotiating tool, the outlook for the trade war would be more benign, with the Administration far more likely to grant concessions and find off-ramps to reduce economic pain and political damage.

However, if you consider all four reasons together, the outlook looks far more challenging. With tariffs, the pain (higher prices) is front loaded, and any gains (new jobs and industries) will take years to deliver. So, success cannot be achieved without digging in and staying the course.

Clearly anticipating a protracted trade war and more volatility, the President is urging Americans to be patient, recently saying “hang tough, it won’t be easy, but the end result will be historic”.

Despite the initial tariffs being at the upper end of expectations, we see scope for tariff rates to rise further as countries pursue ‘tit-for-tat’ retaliation. The US wants countries to buckle and accept the new higher tariff rates.

As Treasury Secretary Bessent recently said “if you retaliate, there will be escalation. If you don’t retaliate, this is the high-water mark”. And by choosing to apply reciprocal tariffs at a so called ‘discounted rate’ of 50%, rather than parity, the US has left room to lift tariff rates higher.

Nevertheless, retaliation is inevitable. Europe, China and Canada haveall stated that they will retaliate in kind. China has announced a matching 34% tariff on all US goods and that it will “fight to the end” if the US persists.

In response, Trump has threatened even higher tariffs, possibly taking the total tariff rate on Chinese exports to the US to 114%. Uncertainty is high and all possibilities remain on the table, but this all points to a protracted trade war with the strong possibility that we have still not yet reached ‘peak tariff’.

An act of economic self-harm? Is stagflation on the horizon?

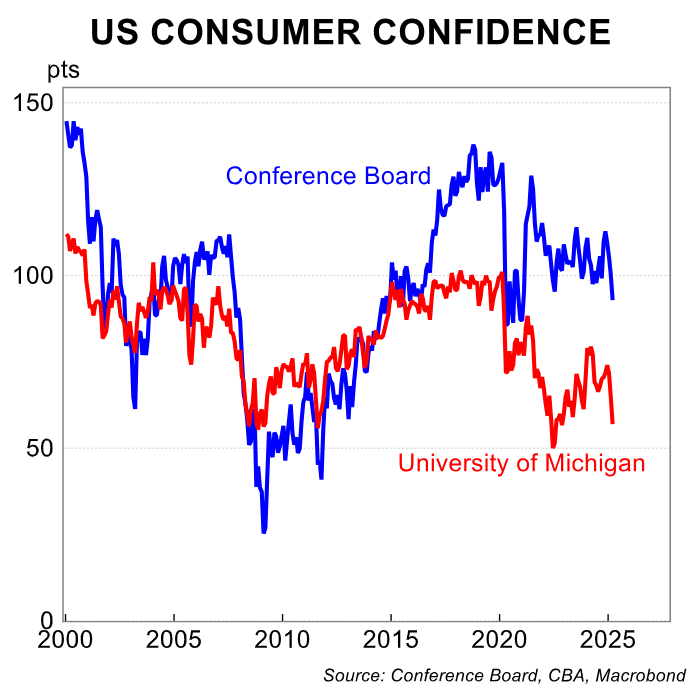

Whatever the longer-term goals, tariffs represent an immediate tax increase on US consumers and importers. An increase of this size is a major shock to the US economy —incomes, growth and confidence will all be lower.

The sharp increase in costs across the economy represents a supply shock that will flow through to higher prices and lower profit margins. In turn, this will flow through to reduced demand for affected goods and lower real household incomes.

Weaker confidence and increased uncertainty will also hold back spending, investment and hiring. The more protracted and messier the trade war, the more damaging for confidence and spending.

The tariff increases will drive an immediate jump in consumer prices in Q2 25, with the likelihood of further increases into H2 25. This essentially represents a one-off (albeit protracted) shift in the price level.

At the same time, the negative hit to US growth will take significant heat out of demand and the labour market. This should dampen broader inflationary pressures across the economy and make it harder for companies to pass on the higher costs of tariffs.

We retain the view that the Federal Reserve will ‘look through’ the one-off impact of tariffs on consumer prices. This suggests they will retain the flexibility to cut interest rates to support a weakening economy in 2025, with the capacity to cut harder if necessary.

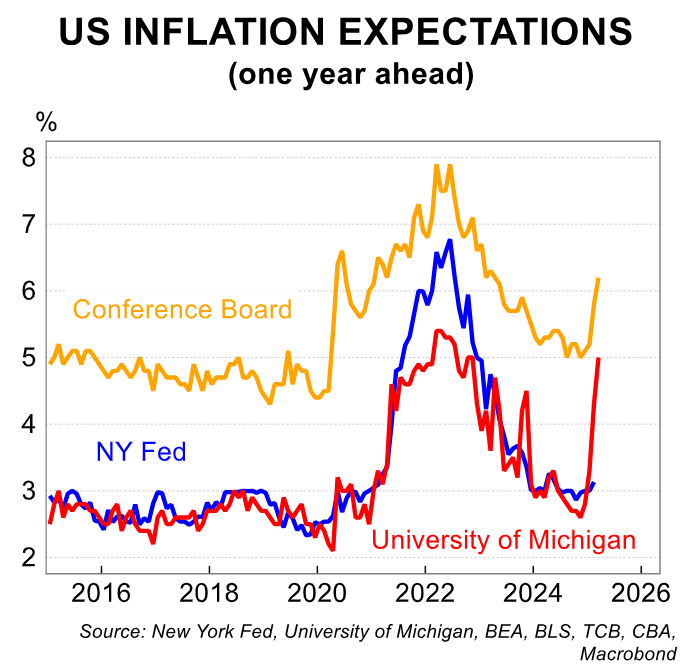

The major risk to this scenario is that inflation expectations de-anchor. After many years of above target inflation another ‘one-off’ price surge could see businesses and workers demand compensation for the ‘new normal’.

If this occurs, the Federal Reserve would be constrained from cutting rates to support economic activity. That is the path to stagflation.

While this scenario cannot be ruled out, it is not our central case. We will update our key forecasts for US and global growth in due course.

Won’t the global economy just adapt?

The global economy is adept at reorganising to avoid trade restrictions. For example, the 2018 trade war saw Chinese exports to the US channelled through other parts of Asia. However, there are key differences this time.

The US consumer remains the largest engine for global growth. Exporters that seek to divert goods to other markets won’t find the same buying power elsewhere, especially during a global tariff induced slowdown.

The tariff increase is so broad-based that opportunities to divert supply chains and reduce the impact will be limited. There will be some re-shuffling based on relative tariff impacts, but complete avoidance seems less likely.

The announcement included high tariff rates on most countries in the highly integrated South-East Asian trading bloc, not just China. This creates less opportunity for those flexible supply chains to find work arounds to avoid tariffs and continue exporting at competitive prices into the US.

There will be some reshoring and eventually an increase in domestic US production to avoid the tariffs. The President will be quick to highlight these new investments at every opportunity.

However, this will not be sufficient to offset the near-term demand shock and will take years to bear fruit. And given operating costs in the US, consumers will still pay more.

How does Australia stand up to the storm?

Overall, Australia is as well placed as anyone to ride out this storm. The Australian economy has sound fundamentals relative to many other key countries.

Strong public spending is providing ongoing support for growth and employment. And our direct trade linkages to the US are small and, at 10%, we face lower tariff rates than many others.

The key impacts on Australia will be indirect, not direct. High tariff rates and lower global demand will make China’s plan to grow at around 5% this year much more difficult.

The impacts of the trade war on Australia will be larger if the Chinese economy slows materially. Much depends on whether the Chinese authorities deploy additional policy stimulus to boost growth.

We consider this likely in the event of a sharp slowdown. Assuming this stimulus includes an infrastructure component, this could provide some additional support for commodity exports.

While the Reserve Bank of Australia will remain cautious and heavily data driven, we consider that weaker global growth will provide another justification for cutting interest rates through this year.