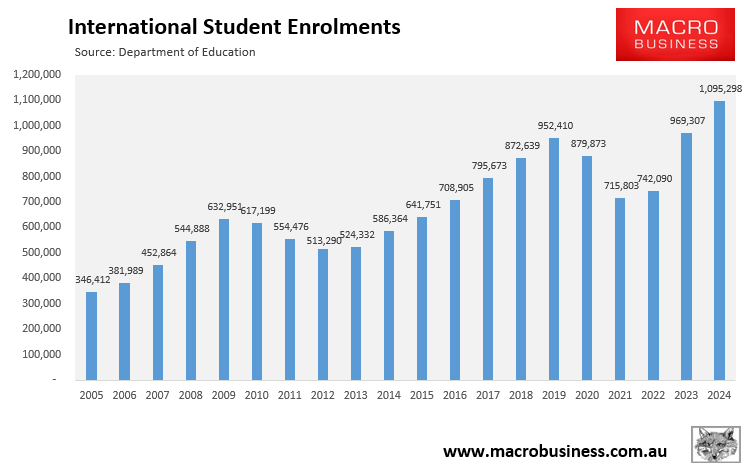

The latest data from the Department of Education shows that a record 1.095 million international students were enrolled in Australia at the end of 2024. This was up by around 150,000 from the pre-COVID peak in 2019 and around 500,000 higher than a decade ago.

It is astounding how a media outlet such as The Guardian can continuously complain about the rental crisis while ignoring the fundamental principle of supply and demand.

The Guardian released a “fact check” on the impact of record numbers of international students on the rental market. This “fact check” was so blatantly biased and misleading that it could have been written by the education and migration lobby.

Central to author Krishani Dhanji’s “fact check” were the findings from two highly flawed and disingenuous studies released by the Property Council and the University of South Australia, both of whom have a vested interest in maintaining higher student volumes:

Just 4% of Australian rentals were taken up by international students (and 6% were taken up by domestic students), according to research from the Property Council of Australia.

However it is based on figures from the 2021 census during which international student numbers were lower because of the pandemic and border closures.

Using the proportion of international students who were renting at the 2016 (pre-Covid) and 2021 censuses to estimate the percentage of the rental market in 2024 would give us a percentage share of 6.8% to 7.2% – or nearly one in every 14 rental properties, at most…

Research by the University of South Australia, published in January, also found there was actually no direct correlation between the cost of rent in Australia and international student numbers…

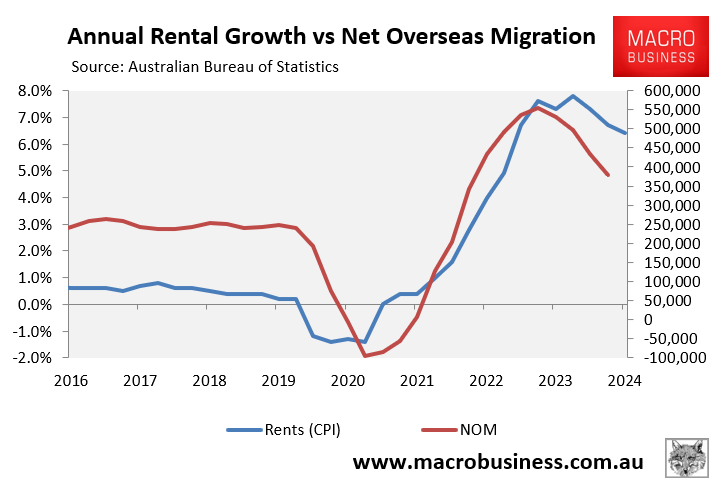

The data is unequivocal: the surge in international students added significantly to rental demand, lowering the vacancy rate and increasing rental inflation.

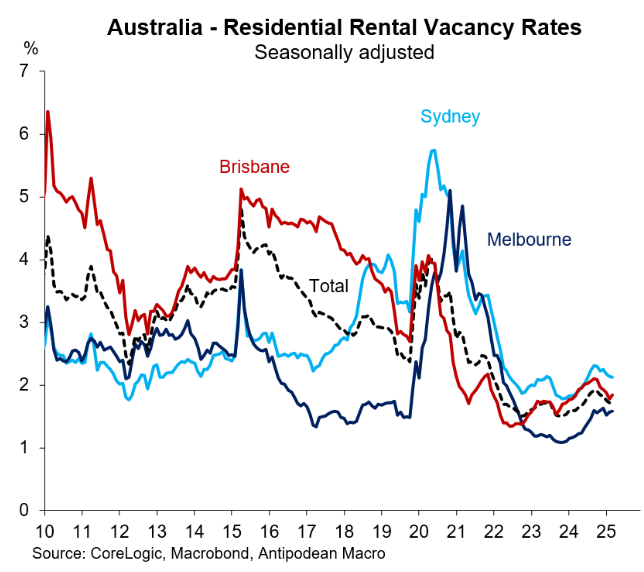

The following chart plots the change in net overseas migration (driven by international students) and CPI rental growth.

When net overseas migration turned negative at the beginning of the pandemic, rental vacancy rates surged and CPI rents fell. When net migration surged to record levels, vacancy rates tightened, and CPI rents soared.

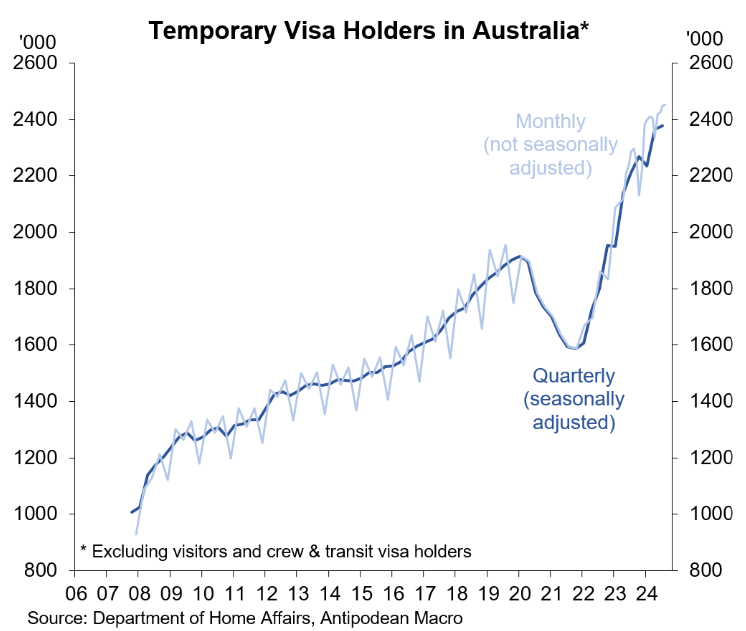

The following chart from Justin Fabo from Antipodean Macro plots the surge in the number of temporary visa holders.

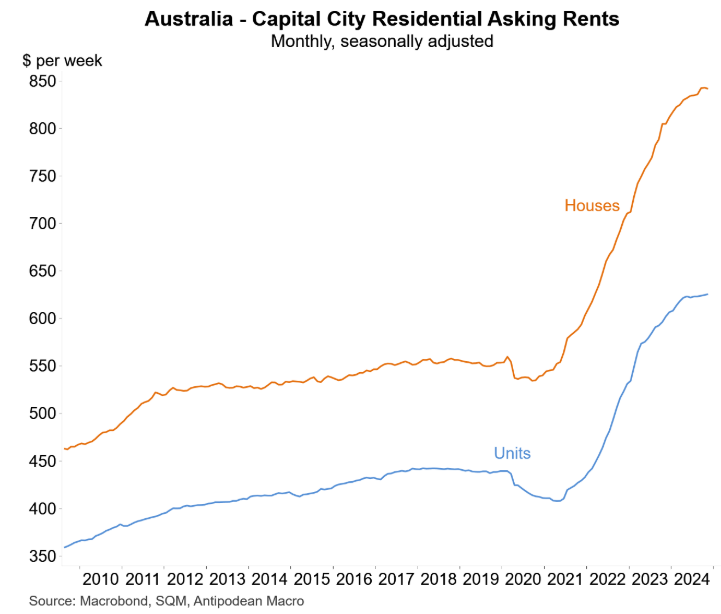

Now compare the above to the following chart from Fabo showing SQM’s asking rent series:

What a coincidence: when the number of temporary visa holders fell, so did asking rents. When temporary visa numbers soared, so did asking rents.

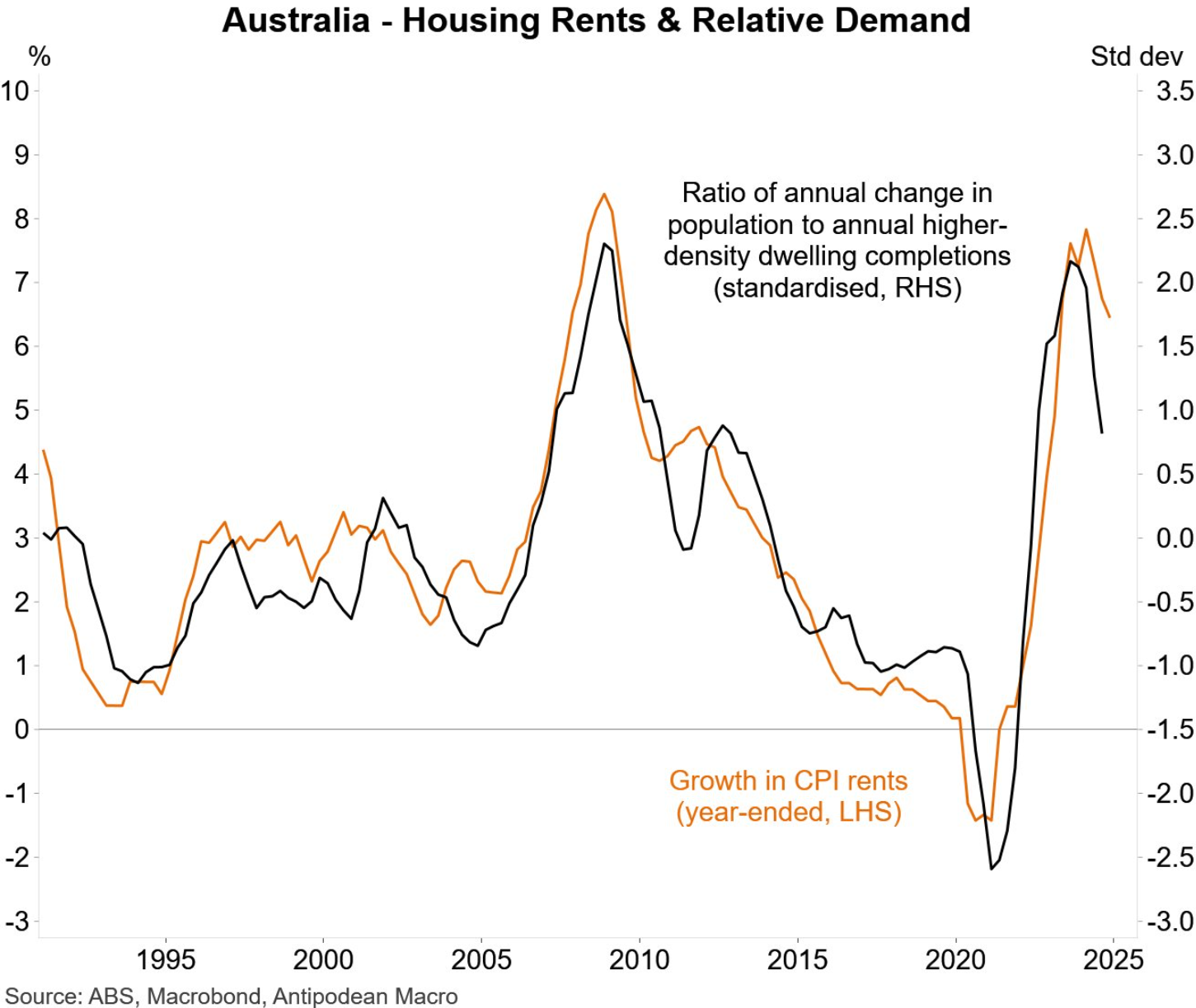

The following chart from Fabo is the knock-out blow. It shows the clear relationship between housing demand/supply and rents.

Increasing immigration through international students in a market with limited supply was disastrous for Australian tenants.

Hilariously, the Guardian’s Krishani Dhanji didn’t bother to cite the fact sheet released by the Department of Education six months ago, which conservatively estimated that international students utilised 7% of Australia’s private rental accommodation, or one in every 14 rental homes.

The Department of Education also explicitly explained how the surge in international students had likely driven up Australia’s rents:

“The Reserve Bank of Australia estimated that a 1% increase in dwelling stock results in the cost of rentals decreasing by 2.5%”.

“A 1% reduction in the demand for private rental properties has an equivalent impact as a 1% increase in dwelling stock and would result in a decrease of rental prices across the market, especially in inner-cities”…

“Rents across Australia rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, but data from SQM research shows that rental prices for units in inner-city locations around most major university campuses dropped significantly from June 2019 to June 2021 when international student numbers were low and rose sharply in the 12 months following the return of students”.

It is also worth reflecting on evidence presented during the pandemic when large volumes of international students departed Australia, leaving many rental homes unoccupied.

In April 2021, the Daily Telegraph posted an article explaining how Sydney property investors were suffering from the slump in rental demand following the loss of international students:

The article noted a study from the Mitchell Institute showing that “landlords near universities in Melbourne and Sydney have been the hardest hit as some suburbs saw international students make up over 25% of all residents before COVID”.

The Mitchell Institute also estimated that 36% of international student spending was on property.

Given that international students are estimated to have spent $51 billion in Australia in 2023-24, this suggests that $18.4 billion was spent on property, mostly rents.

How could this not drive up rental prices?

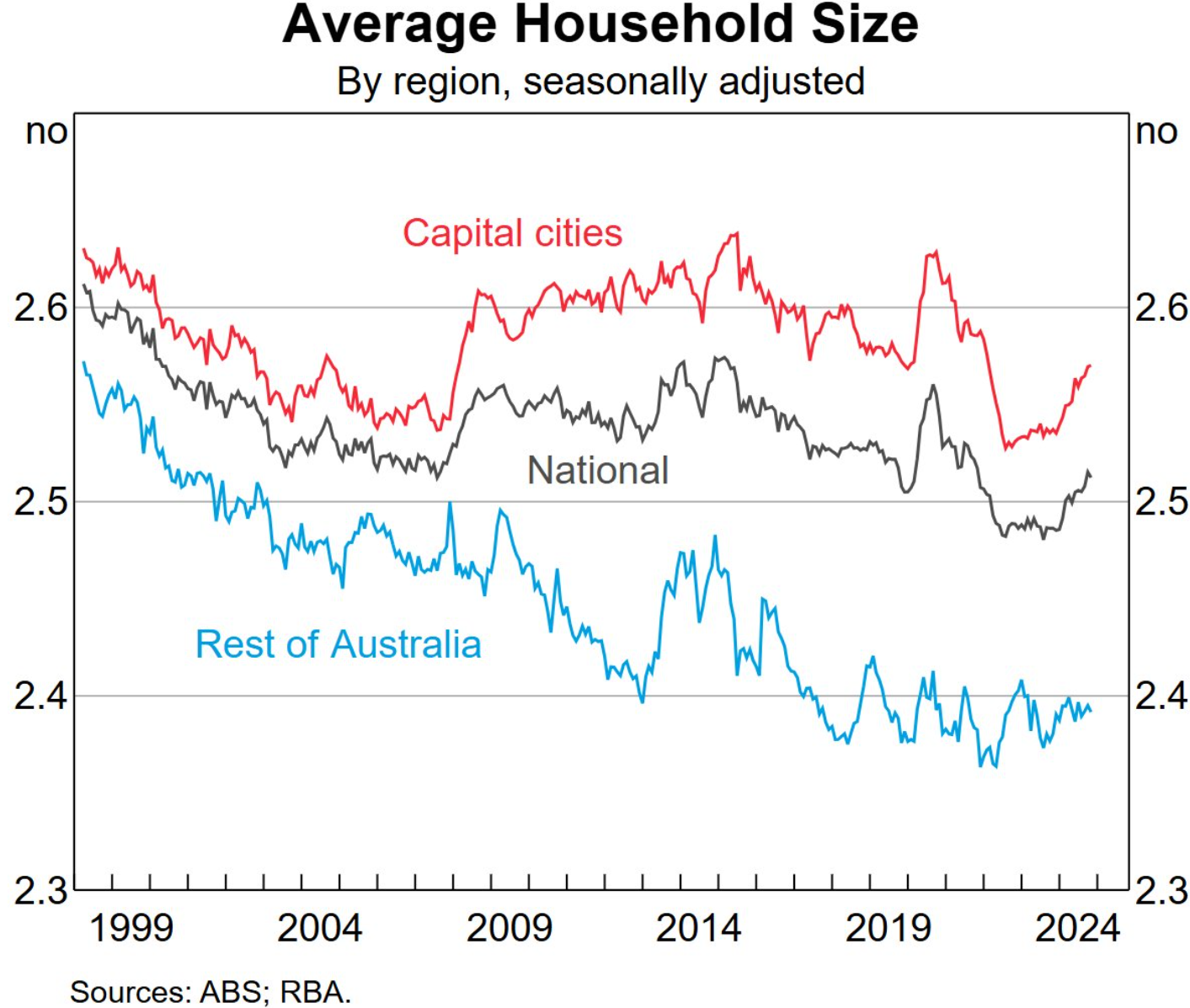

Finally, Dhanji’s “fact check” claimed that the reduction in the number of people per dwelling over the pandemic explains the tightening of the rental market:

The desire for more space that occurred during the pandemic lockdowns, and the number of people living in a household, had continued to drop, leading to more housing pressure.

The RBA assistant governor (economic), Sarah Hunter, said in a speech in May, the average number in a household has dropped from around 2.8 in the mid 1980s to around 2.5 more recently.

“This may sound like a small change. But, if for some reason average household size rose back to 2.8, we would need 1.2 million fewer dwellings to house our current population – no small difference,” she said.

Between late 2020 and August 2022, the RBA estimated that the average household size shrunk from 2.55 individuals to 2.48 individuals nationally, requiring 120,000 additional homes to be built.

However, this argument makes little sense. Australia has an ageing population and fewer households with children. Therefore, the number of people per dwelling should be far less today than it was in the mid-1980s.

Moreover, there are more people per dwelling today than in the mid-2000s, when the “Big Australia” immigration policy began and there were one-third the number of international students.

As a thought experiment: if the 600,000 or so student visa holders in Australia were to suddenly leave, vacating rental properties, would rents:

- Continue rising as these rental homes are left vacant; or

- Fall because renters now have more options?

The answer is obvious and irrefutable. International students boost rental demand and, therefore, put upward pressure on rents.